Titian

Tiziano Vecellio, better known as Titian, the

leader of the 16th-century Venetian school of the Italian High/Late

Renaissance, and the greatest Venetian artist of the

16th century, the shaper of the Venetian coloristic and painterly

tradition. Titian contributed to all of the major areas of Renaissance

art, painting altarpieces, portraits, mythologies, and pastoral

landscapes. He is one of the key figures in the history of Western

art. His work, which permanently affected the course of European

painting, provided an alternative, of equal power and attractiveness,

to the linear and sculptural Florentine tradition championed by

Michelangelo and Raphael; this

alternative, eagerly taken up by Rubens, Diego Velazquez, Rembrandt, Eugene Delacroix, and the Impressionists, is

still vital today. In its own right Titian's work often attains the

very highest reach of human achievement in the visual arts.

Tiziano Vecellio, better known as Titian, the

leader of the 16th-century Venetian school of the Italian High/Late

Renaissance, and the greatest Venetian artist of the

16th century, the shaper of the Venetian coloristic and painterly

tradition. Titian contributed to all of the major areas of Renaissance

art, painting altarpieces, portraits, mythologies, and pastoral

landscapes. He is one of the key figures in the history of Western

art. His work, which permanently affected the course of European

painting, provided an alternative, of equal power and attractiveness,

to the linear and sculptural Florentine tradition championed by

Michelangelo and Raphael; this

alternative, eagerly taken up by Rubens, Diego Velazquez, Rembrandt, Eugene Delacroix, and the Impressionists, is

still vital today. In its own right Titian's work often attains the

very highest reach of human achievement in the visual arts.

Early art of

...Titian

> analysis of art, paintings, and works...

- Christ Carrying the Cross (1507)

- The Concert (1510)

- Portrait of a Woman (La Schiavona) (1510)

- Man with the Blue Sleeve (1510)

- Christ and the Adulteress (1510)

- The Miracle of the Newborn Child (1511)

- The Healing of the Wrathful Son (1511)

- The Gipsy Madonna (1511)

- Pope Alexander VI Presenting Jacopo Pesaro to St. Peter (1511)

- The Three Ages of Man (1512)

- Noli Me Tangere (Don't Touch Me) (1512)

- Woman with a Mirror (1514)

- Sacred and Profane Love (1514)

- Madonna of the Cherries (1515)

- Judith (1515)

- The Tribute Money (1516)

- The Bravo (1517)

- The Assumption of the Virgin (Detail 1) (1518)

- The Worship of Venus (Detail) (1518)

- Venus Anadyomene (1520)

- Madonna and Child with Sts Dorothy and George (1520)

- Flora (1520)

- Portrait of Tomaso or Vincenzo Mosti (1520)

- Polyptych of the Resurrection, Virgin Annunciate (1522)

- Polyptych of the Resurrection, Archangel Gabriel (1522)

- Bacchus and Ariadne (1522)

- St. Christopher (1524)

- Bacchanal of the Andrians (1524)

- Madonna with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family (1526)

- Supper at Emmaus (1530)

- Madonna and Child with St. Catherine and a Rabbit (1530)

- Portrait of Jacopo (Giacomo) Dolfin (Detail) (1532)

- Annunciation (1535)

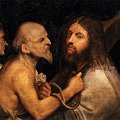

Christ Carrying the Cross (1507)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Christ Carrying the Cross for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the 1570s Titian executed an outstanding series of paintings

dedicated to the passion of Christ. This include the Crowning with Thorns

(Alte Pinakothek, Munich), Mocking of Christ (Art Museum, St. Louis), Ecce

Homo (The Hermitage, St. Petersburg), and two versions of Christ Carrying

the Cross (The Hermitage, St. Petersburg, and Museo del Prado, Madrid). In

these works, pervaded with immense dramatic power, the brushstrokes

gradually dissolve into rapidly applied dabs of pigment. The aim is no

longer to reproduce nature but to directly convey the raw emotion of the

painter, who is participating fully in the tragic subject of his

picture.

a high-quality picture of

Christ Carrying the Cross for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the 1570s Titian executed an outstanding series of paintings

dedicated to the passion of Christ. This include the Crowning with Thorns

(Alte Pinakothek, Munich), Mocking of Christ (Art Museum, St. Louis), Ecce

Homo (The Hermitage, St. Petersburg), and two versions of Christ Carrying

the Cross (The Hermitage, St. Petersburg, and Museo del Prado, Madrid). In

these works, pervaded with immense dramatic power, the brushstrokes

gradually dissolve into rapidly applied dabs of pigment. The aim is no

longer to reproduce nature but to directly convey the raw emotion of the

painter, who is participating fully in the tragic subject of his

picture.

The Concert (1510)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Concert for your computer or notebook. ‣

Cardinal Leopoldo bought this picture in 1654 as a Giorgione and for

centuries it has been assigned to him. It was at the end of the nineteenth

century that Morelli proposed the attribution to Titian, which, in spite

of a recent return to giving it to Giorgione, is generally accepted as the

more persuasive, naturally placing it in Titian's Giorgionesque period,

that is to say his early years.

a high-quality picture of

The Concert for your computer or notebook. ‣

Cardinal Leopoldo bought this picture in 1654 as a Giorgione and for

centuries it has been assigned to him. It was at the end of the nineteenth

century that Morelli proposed the attribution to Titian, which, in spite

of a recent return to giving it to Giorgione, is generally accepted as the

more persuasive, naturally placing it in Titian's Giorgionesque period,

that is to say his early years.

This painting has been considered a work by the young Titian only since it was last restored in 1976. The faces of the figures at the sides are badly damaged. Only the centre figure and the garment of the figure on the right display his masterful use of colour. Pictures of musicians were frequently painted in the 16th century. However, it was very rare for such an intimate relationship between the musicians to be depicted. The youth on the left draws the observer into the scene, thus including him in the web of glances and touches.

The conception and the pictorial rendering appear too full and expansive to allow one to think of Giorgione. Giorgione is considered as the inspirer of the picture, but here there is a greater force than is found in him and a style of painting which is in a certain sense broader. The episode represented (a mere excuse for the presentation of the three ages of man) might well be entitled "Musical Moment". While the elegant youth is absent and distracted, while the old monk seems as it were to placate us with his slow gesture and his intense look in which there is a pitiful sense of comprehension, the young monk in the centre in all his fullness of life "assumes to us the most sublime personification of music and of its bewildering emotions... The figures in the picture are three but such is the intensity of life in the monk who plays than the others seem far away from us - the weakened echoes of great warm voice of passion. (Adolfo Venturi)" The colour is warm and deep; it constructs, it illumines - the living expression of a security of modelling and design which is present and necessary but is subjugated to the poetry of colour.

Portrait of a Woman (La Schiavona) (1510)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Woman (La Schiavona) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The portraits from the early period of Titian are strongly realistic.

Among them the portrait of a woman, called La Schiavone, is of remarkably

fine quality. Titian poses his sitters in such a way as to make the most

of a novel compositional idea; the figures stand out in bold relief against

the plain background and the colour emphasizes the unusual lighting,

revealing the mood of the sitters as well as capturing their physical

presence.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Woman (La Schiavona) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The portraits from the early period of Titian are strongly realistic.

Among them the portrait of a woman, called La Schiavone, is of remarkably

fine quality. Titian poses his sitters in such a way as to make the most

of a novel compositional idea; the figures stand out in bold relief against

the plain background and the colour emphasizes the unusual lighting,

revealing the mood of the sitters as well as capturing their physical

presence.

The inclusion of the sitter's portrait carved in stone may refer to the much discussed issue of the relative merits of painting and sculpture.

Man with the Blue Sleeve (1510)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Man with the Blue Sleeve for your computer or notebook. ‣

The biographer Giorgio Vasari, in his Life of Titian, describes a

similar portrait which he says could easily have been mistaken for a

Giorgione if Titian had not signed it. This portrait was erroneously

identified by early critics as the portrait of Ariosto; it is perhaps a

likeness of Titian's earliest patron, a member of the noble Barbarigo

family.

a high-quality picture of

Man with the Blue Sleeve for your computer or notebook. ‣

The biographer Giorgio Vasari, in his Life of Titian, describes a

similar portrait which he says could easily have been mistaken for a

Giorgione if Titian had not signed it. This portrait was erroneously

identified by early critics as the portrait of Ariosto; it is perhaps a

likeness of Titian's earliest patron, a member of the noble Barbarigo

family.

In his early period, Titian's portraits are strongly realistic. The painting in its gripping tonal palpability and attention to detail, such as the stitching in the satin, has much in common with Giorgione's late portraits. But Titian, somewhat competitively, carries Giorgione's realism a step further in the way the sleeve billows out and invades our space, extending the boundaries of Giorgionismo in a burst of hyperrealism. The sitter's expression is arrogant, typical of the male dandy. The figure stands out in bold relief against the plain background and the colour emphasizes the unusual lighting, revealing the mood of the sitter as well as capturing his physical presence.

Christ and the Adulteress (1510)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Christ and the Adulteress for your computer or notebook. ‣

Christ and the Adulteress depicts the gospel story in which Christ was

challenged by the Pharisees to condemn a woman caught in the act of

adultery. Although formerly widely considered to be by Giorgione, it is

now generally held to be by the young Titian. Its revolutionary character

is clearly evident when seen against the background of the artistic

tradition represented by Giovanni Bellini. Fifteenth-century compositions,

even those with narrative subjects, tended to be calm and static. Here, by

contrast, poses and gestures are bold and vehement, the figures possess a

new physical robustness, and the colours of the draperies are glowingly

sensuous. Whereas fifteenth-century pictures were typically painted on the

smooth, glassy surface of primed and polished wood, this - like virtually

all of Titian's subsequent work - is painted on the more uneven surface of

canvas, and the oil paint applied with more visible brushstrokes.

a high-quality picture of

Christ and the Adulteress for your computer or notebook. ‣

Christ and the Adulteress depicts the gospel story in which Christ was

challenged by the Pharisees to condemn a woman caught in the act of

adultery. Although formerly widely considered to be by Giorgione, it is

now generally held to be by the young Titian. Its revolutionary character

is clearly evident when seen against the background of the artistic

tradition represented by Giovanni Bellini. Fifteenth-century compositions,

even those with narrative subjects, tended to be calm and static. Here, by

contrast, poses and gestures are bold and vehement, the figures possess a

new physical robustness, and the colours of the draperies are glowingly

sensuous. Whereas fifteenth-century pictures were typically painted on the

smooth, glassy surface of primed and polished wood, this - like virtually

all of Titian's subsequent work - is painted on the more uneven surface of

canvas, and the oil paint applied with more visible brushstrokes.

The Miracle of the Newborn Child (1511)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Miracle of the Newborn Child for your computer or notebook. ‣

One of Titian's scenes in the Scuola del Santo depicts The Miracle of

the Newborn Child. St Anthony worked a miracle in which a newly born child

spoke in defence of his mother, who had been accused of adultery. The

closely observed, very individual faces show Titian's mastery of his

craft, even at this early stage of his career.

a high-quality picture of

The Miracle of the Newborn Child for your computer or notebook. ‣

One of Titian's scenes in the Scuola del Santo depicts The Miracle of

the Newborn Child. St Anthony worked a miracle in which a newly born child

spoke in defence of his mother, who had been accused of adultery. The

closely observed, very individual faces show Titian's mastery of his

craft, even at this early stage of his career.

The Healing of the Wrathful Son (1511)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Healing of the Wrathful Son for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Scuola del Santo in Padua, the house where the brotherhood of St

Anthony met, was on the edge of the square in front of the church in which

the famous Franciscan saint was buried. In 1510-11 Titian worked alongside

other painters to decorate two walls in the upper assembly room (Sala

Capitolare) with frescoes depicting miracles from the saint's life. He

painted three scenes from the Life of St Anthony of Padua. They are the

first of Titian's works that can be definitely dated and that still exist

in their entirety.

a high-quality picture of

The Healing of the Wrathful Son for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Scuola del Santo in Padua, the house where the brotherhood of St

Anthony met, was on the edge of the square in front of the church in which

the famous Franciscan saint was buried. In 1510-11 Titian worked alongside

other painters to decorate two walls in the upper assembly room (Sala

Capitolare) with frescoes depicting miracles from the saint's life. He

painted three scenes from the Life of St Anthony of Padua. They are the

first of Titian's works that can be definitely dated and that still exist

in their entirety.

One of Titian's scenes depicts The Healing of the Wrathful Son. St Anthony reattached the foot of a young man who had cut it off in an outburst of violent temper because he had hurt his mother with it. Despite the difficulty of working on frescoes, which demanded great speed on the part of the artist, Titian succeeded in producing splendid landscapes.

The Gipsy Madonna (1511)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Gipsy Madonna for your computer or notebook. ‣

The first and best known of an early series of Madonnas in a landscape

setting is the Gypsy Madonna. This painting got its name from the black

hair and pale face of the Madonna, as well as the charming contrast of

colours. This type of Madonna, with very dark eyes, is not found in

Titian's later works.

a high-quality picture of

The Gipsy Madonna for your computer or notebook. ‣

The first and best known of an early series of Madonnas in a landscape

setting is the Gypsy Madonna. This painting got its name from the black

hair and pale face of the Madonna, as well as the charming contrast of

colours. This type of Madonna, with very dark eyes, is not found in

Titian's later works.

In contrast to the remoter Madonnas of Giovanni Bellini, the Gypsy Madonna has a radiating warmth, an expansive physicality, but the composition still derives from a Bellini prototype. In the Bellini, the child faces directly out, and X-rays show this was originally the case with the Titian. They also demonstrate how Titian adhered to the Giorgionesque practice of making radical changes during the painting process. This differed from earlier generations of Venetian artists and central Italian artists, who were more likely to have worked everything out beforehand in preparatory drawings or underdrawing on the support and less likely to make major alterations after starting to paint.

Pope Alexander VI Presenting Jacopo Pesaro to St. Peter (1511)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Pope Alexander VI Presenting Jacopo Pesaro to St. Peter for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting was painted to celebrate the defeat of the Turks at Santa

Maura on 30 August 1502: the victorious papal fleet was led by Jacopo

Pesaro while his cousin Benedetto commanded the allied Venetian fleet.

a high-quality picture of

Pope Alexander VI Presenting Jacopo Pesaro to St. Peter for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting was painted to celebrate the defeat of the Turks at Santa

Maura on 30 August 1502: the victorious papal fleet was led by Jacopo

Pesaro while his cousin Benedetto commanded the allied Venetian fleet.

Due to its awkward passages, this used to be considered one of Titian's very earliest paintings and dated c. 1506. However, the painting has notable stylistic similarities with the altarpiece in the Santa Maria della Salute (St Mark Enthroned with Saints) which is dated c. 1510, thus the Antwerp painting should be given a later dating around 1510.

The Three Ages of Man (1512)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Three Ages of Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting represents the artist's conception of the life cycle

in allegorical terms. Childhood, manhood synonymous with earthly love,

and old age approaching death are drawn realistically as each figure

reflects Titian's attitudes toward each stage of earthly existence. A

plump angel floats ethereally over two sleeping babies, protecting

them, but also mirroring their purity.

a high-quality picture of

The Three Ages of Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting represents the artist's conception of the life cycle

in allegorical terms. Childhood, manhood synonymous with earthly love,

and old age approaching death are drawn realistically as each figure

reflects Titian's attitudes toward each stage of earthly existence. A

plump angel floats ethereally over two sleeping babies, protecting

them, but also mirroring their purity.

To the left, he paints the joys (and exhaustion) of youth, the firmly muscled, mature male, perhaps spent from a sexual encounter, being tantalized by a pubescent girl dressed in provocative style to further endeavors. She holds two flutes and by chance is urging him on with her piped, "Siren's song."

In the background, at the end of his days, a bearded old, stooped man gazes at two skulls, either in terror or in wonder. The exquisite detailed scenery reflects nature in her glory and decline - lofty, weightless clouds float through an azure sky. Parched trees in the foreground reflect the arid remnants of summer landscapes, as the skulls reflect those of man.

"In life, we are in death," the philosopher tells us. In an age when people died so young, perhaps Titian is reflecting the same attitude by placing all of these figures in the same landscape. Perhaps the angel is not only protecting the infants, but also reminding us that in Titian's day, children died at a frightening rate, inconceivable in this modern age, and his/her home in heaven is the destination to which they will soon be transported.

Noli Me Tangere (Don't Touch Me) (1512)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Noli Me Tangere (Don't Touch Me) for your computer or notebook. ‣

When the young Titian painted the appearance of the resurrected

Christ to Mary Magdalen, loosely based on the scene recounted in the

Gospel of John (20: 11-18), he proposed a remarkably original

interpretation. He clearly knew the masterpieces of his predecessors,

such as Giotto, Fra Angelico, etc., but had no hesitation in inventing

a type of representation which gave new life to the theme. Titian,

whose real name was Tiziano Vecellio, was then only about twenty and

had, in 1510, just lost the master who, through the stress he placed

on landscape and light, had had the greatest influence on him -

Giorgione. For Titian, landscape was henceforth never just an

afterthought but was an integral part of a painting.

a high-quality picture of

Noli Me Tangere (Don't Touch Me) for your computer or notebook. ‣

When the young Titian painted the appearance of the resurrected

Christ to Mary Magdalen, loosely based on the scene recounted in the

Gospel of John (20: 11-18), he proposed a remarkably original

interpretation. He clearly knew the masterpieces of his predecessors,

such as Giotto, Fra Angelico, etc., but had no hesitation in inventing

a type of representation which gave new life to the theme. Titian,

whose real name was Tiziano Vecellio, was then only about twenty and

had, in 1510, just lost the master who, through the stress he placed

on landscape and light, had had the greatest influence on him -

Giorgione. For Titian, landscape was henceforth never just an

afterthought but was an integral part of a painting.

Thus we see here the meeting of Christ with Mary Magdalen in the middle of a landscape which seems to be one with them, such do the lines of the natural setting continue or rhythmically complement those of the two people. We are no longer in the garden of the tomb as described by John (19: 41), but in the open countryside bathed in morning light. On Mary's side, the curve of a hillside and an earthly settlement is echoed by the inverse curve of her body thrown forward to the ground. Christ's side of the painting opens out onto the blue tinged distances of infinity.

But these two different worlds - human and divine - suggested by the division of space are subtly linked to each other: the bend of Christ's body is a direct continuation of the curve of the inhabited hillside; the line of Mary's raised torso continues that of a tree which, while balancing the right side of the landscape, directs the mind of the observer to the idea of a new life. Everything in this highly sophisticated composition is designed to underscore the importance of the gestural and verbal dialogue taking place in the foreground and to highlight the novelty of the message it conveys.

Mary Magdalen has just recognized Jesus by the tone of voice in which he calls out "Mary!". Titian shows the surge of emotion which casts her to the ground, an impulse just as quickly suppressed by Christ who draws back, speaking the words, Noli me tangere, "Don't touch me." The painter has left out most of the references which traditionally help to identify the scene: there is no tomb, no herald angel, no halo, no standard marked with the cross in the hand of the resurrected Lord.

Titian contents himself with placing a hoe in Jesus' hand, a reference to Mary's first mistaken impression of him (she mistook him for a gardener), and by placing in the woman's hand the now unneeded jar of ointment. Rather, the painter innovates by evoking the resurrection through the nakedness of Christ's body, covered only by the shroud in which he had been buried - a shroud whose white draping magnificently complements the red flow of Mary's garment. He accentuates the tension in the woman's movement and the closeness of the two people whose right hands would touch were it not for Christ pulling back in a subtle movement of refusal nuanced by the affectionate inclination of his torso bending over Mary Magdalen.

The atmosphere is that of the dialogue between the lover and the beloved in the Song of Songs: "I sought him whom my heart loves." Here Mary Magdalen finds the beloved she had lost only to be immediately asked to let him go again, to 'stop holding on to him' and to go back to his brothers to share with them the news that is to transform their lives (Jn 20: 18).

For Christ is just passing by. His dance like steps are directed towards the front of the painting, not towards Mary but towards us, the viewers. We thus find ourselves facing the Lord's approach, also invited to recognize him and to announce the joy of his resurrection.

Woman with a Mirror (1514)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Woman with a Mirror for your computer or notebook. ‣

Titian's early series of female portraits are one of the glories of the

Venetian Renaissance. Depicted with loving care, his sitters - however

idealized in the final composition - are too full of life and character

not to have been taken from the model.

a high-quality picture of

Woman with a Mirror for your computer or notebook. ‣

Titian's early series of female portraits are one of the glories of the

Venetian Renaissance. Depicted with loving care, his sitters - however

idealized in the final composition - are too full of life and character

not to have been taken from the model.

The Woman with a Mirror is probably among the earliest of these works: in comparison to others in the series, she is seen from a more frontal angle behind the parapet and in terms of atmosphere appears less integrated within the ambient space. She stands between two mirrors held up by an admirer in such a way that she can see herself and her admirer and we can see her from both front and back. This arrangement refers to the claims of painting to surpass sculpture, by presenting an all-round view with colour as a bonus. Her expression has little to do with vanity, a common gloss on images of women before a mirror, and shows an unaffected and dawning delight in her own attractions which the viewer, like her admirer, is expected to share. Thus the picture is a celebration of her beauty, enhanced by the possibility of its being admired from different aspects by all concerned - herself, her lover and the spectator.

Sacred and Profane Love (1514)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Sacred and Profane Love for your computer or notebook. ‣

Sacred and Profane Love, Titian's masterpiece, was painted

when he was about twenty-five to celebrate the marriage of the

Venetian Nicolo Aurelio (coat of arms on the sarcophagus) and Laura

Bagarotto in 1514. The bride dressed in white sitting beside Cupid is

assisted by Venus in person. The figure with the vase of jewels

symbolizes 'fleeting happiness on earth' and the one bearing the

burning flame of God's love symbolizes 'eternal happiness in heaven'.

The title is the result of a late 18th-century interpretation of the

painting, which gives a moralistic reading of the nude figure, whereas

the artist intended this to be an exaltation of both earthly and

heavenly love. In fact in the Neoplatonic philosophy that Titian and

his circle believed in contemplating the beauty of the creation led to

an awareness of the divine perfection of the order of the cosmos.

a high-quality picture of

Sacred and Profane Love for your computer or notebook. ‣

Sacred and Profane Love, Titian's masterpiece, was painted

when he was about twenty-five to celebrate the marriage of the

Venetian Nicolo Aurelio (coat of arms on the sarcophagus) and Laura

Bagarotto in 1514. The bride dressed in white sitting beside Cupid is

assisted by Venus in person. The figure with the vase of jewels

symbolizes 'fleeting happiness on earth' and the one bearing the

burning flame of God's love symbolizes 'eternal happiness in heaven'.

The title is the result of a late 18th-century interpretation of the

painting, which gives a moralistic reading of the nude figure, whereas

the artist intended this to be an exaltation of both earthly and

heavenly love. In fact in the Neoplatonic philosophy that Titian and

his circle believed in contemplating the beauty of the creation led to

an awareness of the divine perfection of the order of the cosmos.

In this painting of love in the open countryside Titian has surpassed the delicate lyrical poetry of Giovanni Bellini or Giorgione and attributes a classical grandeur to his figures. In 1899, the Rothschilds offered to buy this world famous work at a price that was higher than the estimated value of the Villa Borghese and all its works of art (4,000,000 Lire as opposed to 3,600,000 Lire) . However, Titian's Sacred and Profane Love has remained and virtually become the symbol of the Borghese Gallery itself.

Madonna of the Cherries (1515)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna of the Cherries for your computer or notebook. ‣

In this half-length picture of the Madonna, Titian was still keeping

entirely to a pictorial idiom typical of Giovanni Bellini. St Joseph is on

the left, and Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist, on the right of

the Madonna. John, depicted as a naked boy, is giving the Madonna the

cherries that give the painting its name.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna of the Cherries for your computer or notebook. ‣

In this half-length picture of the Madonna, Titian was still keeping

entirely to a pictorial idiom typical of Giovanni Bellini. St Joseph is on

the left, and Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist, on the right of

the Madonna. John, depicted as a naked boy, is giving the Madonna the

cherries that give the painting its name.

Judith (1515)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Judith for your computer or notebook. ‣

This masterpiece, one of the finest and most poetical of Titian's

creations, is unanimously dated by the critics at around 1515. The main

focus is on neither the horrific events nor the religious significance of

the scene. It is not even clear if this is Salome with the head of the

Baptist, or Judith with the head of Holofernes. The former is suggested by

the displaying of the head on a platter, the latter by the presence of the

female servant who is a feature of the traditional iconography of the

Judith story.

a high-quality picture of

Judith for your computer or notebook. ‣

This masterpiece, one of the finest and most poetical of Titian's

creations, is unanimously dated by the critics at around 1515. The main

focus is on neither the horrific events nor the religious significance of

the scene. It is not even clear if this is Salome with the head of the

Baptist, or Judith with the head of Holofernes. The former is suggested by

the displaying of the head on a platter, the latter by the presence of the

female servant who is a feature of the traditional iconography of the

Judith story.

Both at the time when the painting was in the collection of the Duchess of Urbino, and later, when it belonged to the Aldobrandini family, it was believed to depict Herodias, Herod's wife and the mother of Salome. However, a number of foreign visitors who had an opportunity to see Titian's painting in the Villa Aldobrandini at Montecavallo thought it to be a representation of Judith. This common belief is also reflected in modern historiography. In fact, if the figure in the painting were Herodias, dressed here in bright red, carrying the head of John the Baptist on a tray, then the girl in the green dress on her right would have to be Salome. Yet there is nothing regal about the two women, while the seductive attitude of the main figure is well suited to the Jewish heroine Judith, a rich and attractive widow who, with her oppressor Holofernes decapitated, now holds the head with the assistance of her maid. This theme was often treated as a symbol of virtue.

That this interpretation of the subject may be the correct one is also confirmed by the fact that there is a 1533 record of a Judith by Titian in the collection of Alfonso I d'Este. Considered lost, there cannot be the slightest doubt that it is this painting, which comes in fact from the collection of Lucrezia d' Este, granddaughter of Alfonso I.

The painting, with its wonderful colour contrasts of red, green, and white, and its delightful female figures, is one of Titian's depictions of an ideal of female beauty. This is why it was frequently copied.

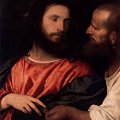

The Tribute Money (1516)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Tribute Money for your computer or notebook. ‣

"Render therefore unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto

God the things that are God's" (Matt. 22:21) was a fundamental text for

relations between Church and State, and sound advice for the patron

Alfonso d'Este, who owed allegiance to both the Pope and the Holy Roman

Emperor.

a high-quality picture of

The Tribute Money for your computer or notebook. ‣

"Render therefore unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto

God the things that are God's" (Matt. 22:21) was a fundamental text for

relations between Church and State, and sound advice for the patron

Alfonso d'Este, who owed allegiance to both the Pope and the Holy Roman

Emperor.

The Bravo (1517)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Bravo for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the 17th century the painting was attributed to Giorgione, and later

for a long time to Palma Vecchio. However, recently it was given to

Tiziano.

a high-quality picture of

The Bravo for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the 17th century the painting was attributed to Giorgione, and later

for a long time to Palma Vecchio. However, recently it was given to

Tiziano.

The Bravo, so called because of the mysterious armed man with his back to us, falls into Titian's Giorgionesque phase and demonstrates an undercurrent of cruelty. The subject has been convincingly identified as the arrest of Bacchus by Pentheus, King of Thebes, who opposed the Bacchic cult. Bacchus' revenge was dire, and Pentheus was torn to pieces by his mother and sisters.

The Assumption of the Virgin (Detail 1) (1518)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Assumption of the Virgin (Detail 1) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Altar-painting: Church of St. Maria dei Frari, Venice.

a high-quality picture of

The Assumption of the Virgin (Detail 1) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Altar-painting: Church of St. Maria dei Frari, Venice.

Titian's first major public commission in Venice, the Assumption of the Virgin for the high altar of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari (1516-18), Venice, established his place as the leading painter of the city. Contemporaries noted that some viewers were uneasy with its novel portrayal of the dynamically twisting Virgin and the gesticulating apostles below. It broke with tradition as well in the heroic scale of the figures and the use of bold color. The Assumption can be seen from the far end of the church, drawing the eye to the sacred space of the altar.

Titian's uniqueness lies in his almost mystical use of colour. Where Florentine artists such as Michelangelo began by drawing the figure, Titian painted more freely, with a thick, richly textured surface obtained by painting on rough twill canvas, and with an uncanny understanding of light. In a sense Titian is a scientist, an experimenter in the optical effects of colour relationships and the way in which we retain visual memories. Titian tested his pigments' brightness in the most audacious way in this Assumption altarpiece in the church of the Frari in Venice, a light-filled painting set against a vast window, complementing the light of nature - and rivalling it. "The sun is God" said Turner. In painting, Titian is.

Titian worked on this huge altarpiece for more than two years from 1516 to 1518. It has to be seen as a milestone in Titian's career establishing him as a more universal artist who drew inspiration from outside the confines of Venice. Indeed the powerful figures of the Apostles reflect the influence of Michelangelo, whereas the painting demonstrates clear iconographical similarities with the works of Raphael. Above all, what emerges most strongly in the assumption is Titian's desire to break definitely with the traditions of Venetian painting in order to arrive at a synthesis of dramatic force and dynamic tension which will become from this moment on the most obvious characteristic of his work.

The picture is composed of three orders. At the bottom are the Apostles (humanity), amazed and stunned by the wondreous happening. St. Peter is kneeling with his hand on his breast, St. Thomas is pointing at the Virgin, and St. Andrew in a red cloak is stretching forward. In the middle, the Madonna, slight and bathed in light, is surrounded by by a host of angels that accompany her joyfully hailing. Above is the Eternal Father, serene and noble majesty, calling the Virgin to him with a look of love. The painting is signed as Ticianus low down in the middle of the picture.

The Worship of Venus (Detail) (1518)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Worship of Venus (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

In classical times, Cupids were considered to be the children of

nymphs, who were the female nature spirits who were closely linked to

Venus. Titian depicted every one with a precise eye for the enchanting

freshness and comic gestures of small children.

a high-quality picture of

The Worship of Venus (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

In classical times, Cupids were considered to be the children of

nymphs, who were the female nature spirits who were closely linked to

Venus. Titian depicted every one with a precise eye for the enchanting

freshness and comic gestures of small children.

Venus Anadyomene (1520)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Venus Anadyomene for your computer or notebook. ‣

The word "Anadyomene", which means "one who has surfaced", is a

reference to the birth of Venus. According to classical mythology and the

poetry of Hesiod (ca. 700 BC), Venus rose fully formed from the ocean in

Paphos on Cyprus (or Cythera). This is the moment depicted by Titian. The

relatively small painting shows one of his women's figures typical of the

1510s and 1520s. This painting should be seen not as a portrait of an

individual but as a depiction of female beauty.

a high-quality picture of

Venus Anadyomene for your computer or notebook. ‣

The word "Anadyomene", which means "one who has surfaced", is a

reference to the birth of Venus. According to classical mythology and the

poetry of Hesiod (ca. 700 BC), Venus rose fully formed from the ocean in

Paphos on Cyprus (or Cythera). This is the moment depicted by Titian. The

relatively small painting shows one of his women's figures typical of the

1510s and 1520s. This painting should be seen not as a portrait of an

individual but as a depiction of female beauty.

Madonna and Child with Sts Dorothy and George (1520)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna and Child with Sts Dorothy and George for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the relaxed and confident painting Titian brings the charms of the

family circle to the well-tried formula of the Sacra Conversazione. St

Dorothy's indulgent smile is that of a visiting relative while the noble

St George irresistibly recalls the avuncular bore, always right, taking

himself very seriously, and full of the best and dullest advice. The green

curtain bracketing the brighter colours of the figures supports this mood

of secure domesticity.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna and Child with Sts Dorothy and George for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the relaxed and confident painting Titian brings the charms of the

family circle to the well-tried formula of the Sacra Conversazione. St

Dorothy's indulgent smile is that of a visiting relative while the noble

St George irresistibly recalls the avuncular bore, always right, taking

himself very seriously, and full of the best and dullest advice. The green

curtain bracketing the brighter colours of the figures supports this mood

of secure domesticity.

X-rays show that both the child and St George originally faced outwards, which would have made the picture more old-fashioned and more formal.

Flora (1520)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Flora for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is one of Titian's most beautiful works, which, in the warm and

impassioned intensity of the colour, sums up the youthful period of

Titian. The beautiful woman carrying flowers is thought to be Flora, the

classical goddess of flowers and spring. The title of Flora goes back to

an engraving which was made from the picture in the 17th century by

Sandrart.

a high-quality picture of

Flora for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is one of Titian's most beautiful works, which, in the warm and

impassioned intensity of the colour, sums up the youthful period of

Titian. The beautiful woman carrying flowers is thought to be Flora, the

classical goddess of flowers and spring. The title of Flora goes back to

an engraving which was made from the picture in the 17th century by

Sandrart.

This painting is one of the first of a series of portraits of ideal female beauty that Titian painted. The sheen of her reddish golden hair, the soft hue of her skin, and the just visible breast whose bareness is skillfully emphasized by her hand and the pink brocade, display Titian's abilities as a subtle colourist and his sure feeling for sensuality.

In the 17th century, the Flora came to the Netherlands and inspired Rembrandt to paint his wife Saskia in the same guise, albeit less scantily clad.

Portrait of Tomaso or Vincenzo Mosti (1520)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Tomaso or Vincenzo Mosti for your computer or notebook. ‣

There is an inimitable elegance in the way Titian links the various

shades of gray in the garment to those in the background. Gray silk, fur

and a lace shirt all become tactile sensations. An inscription which used

to be on the back of the portrait identified the figure as Tomaso Mosti.

Some authors, however, think it more likely that this is his brother

Vincenzo. The reason is that Tomaso was a priest, while Vincenzo, in

contrast, was a favourite of Alfonso d'Este at the court of Ferrara.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Tomaso or Vincenzo Mosti for your computer or notebook. ‣

There is an inimitable elegance in the way Titian links the various

shades of gray in the garment to those in the background. Gray silk, fur

and a lace shirt all become tactile sensations. An inscription which used

to be on the back of the portrait identified the figure as Tomaso Mosti.

Some authors, however, think it more likely that this is his brother

Vincenzo. The reason is that Tomaso was a priest, while Vincenzo, in

contrast, was a favourite of Alfonso d'Este at the court of Ferrara.

Polyptych of the Resurrection, Virgin Annunciate (1522)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Polyptych of the Resurrection, Virgin Annunciate for your computer or notebook. ‣

The detail shows the Virgin Annunciate.

a high-quality picture of

Polyptych of the Resurrection, Virgin Annunciate for your computer or notebook. ‣

The detail shows the Virgin Annunciate.

In an age that was completely shaped by Christianity, it would have been obvious that the two top panels, showing Mary on the right and an angel on the left, belonged together as an Annunciation. This was also an arrangement found in many other polyptychs. Without knowing this, however, it would be quite conceivable to see both scenes as part of the central scenes, the Resurrection of Christ.

Polyptych of the Resurrection, Archangel Gabriel (1522)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Polyptych of the Resurrection, Archangel Gabriel for your computer or notebook. ‣

The detail shows the Angel of the Annunciation.

a high-quality picture of

Polyptych of the Resurrection, Archangel Gabriel for your computer or notebook. ‣

The detail shows the Angel of the Annunciation.

The Archangel Gabriel (top left panel of the polyptych of the Resurrection) appears to be rushing in from the left, his garments streaming behind him. He spreads his greeting out on a banderole, which he is holding out to Mary on the opposite panel. His right hand, part of the banderole, his wings and the fluttering ends of his belt are all cut off by the edge of the picture. This creates the impression that the almost square panel is much too small to contain the magnificent figure of the angel. This artistic trick enables Titian to intensify the sense of tension and dynamics of the painting.

Bacchus and Ariadne (1522)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Bacchus and Ariadne for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1516 Titian made contact with Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara for

whom he was to work for a decade on pictures destined for the Alabaster

Chamber. In this period he painted a series of magnificent paintings of

Dionysian themes: the Worship of Venus in the Prado, The Andrians

(Bacchanalia), also in the Prado, and Bacchus and Ariadne, in the National

Gallery, London. In these paintings Titian combines a richness of

colouristic expression with a great formal elegance. These are the

elements which characterize this whole so-called "classic" phase of

Titian's development and which is dominated by the supreme masterpiece of

the Frari Assumption of the Virgin.

a high-quality picture of

Bacchus and Ariadne for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1516 Titian made contact with Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara for

whom he was to work for a decade on pictures destined for the Alabaster

Chamber. In this period he painted a series of magnificent paintings of

Dionysian themes: the Worship of Venus in the Prado, The Andrians

(Bacchanalia), also in the Prado, and Bacchus and Ariadne, in the National

Gallery, London. In these paintings Titian combines a richness of

colouristic expression with a great formal elegance. These are the

elements which characterize this whole so-called "classic" phase of

Titian's development and which is dominated by the supreme masterpiece of

the Frari Assumption of the Virgin.

Titian's sources for the Bacchus and Ariadne were a variety of classical texts (especially Catullus and Ovid), all of them concerning Ariadne, the daughter of the king of Crete. Because of her love for Theseus, she helped him escape her father's labyrinth by means of a ball of thread. However, Theseus deserted her on Naxos while they were returning to Athens. There, she became the lover of the god Bacchus. Above her, already visible, is a crown of stars representing the "Corona Borealis", into which she (or, according to a different tradition, her bridal head-dress) is eventually transformed.

This painting is among Titian's most Raphaelesque, particularly in the contrapposto of Ariadne and the controlled energy of Bacchus and his train, who seem more numerous than they really are. To achieve colouristic brilliance, Titian has used the strongest pigments then available on the market.

St. Christopher (1524)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Christopher for your computer or notebook. ‣

Titian was involved in a number of public works undertaken by Doge

Andrea Gritti. This St Christopher is over the staircase leading to the

doge's private apartment as a talisman against assassination. The huge

saint ensures the insouciant Child's protection for Venice, admirably

depicted in the distance.

a high-quality picture of

St. Christopher for your computer or notebook. ‣

Titian was involved in a number of public works undertaken by Doge

Andrea Gritti. This St Christopher is over the staircase leading to the

doge's private apartment as a talisman against assassination. The huge

saint ensures the insouciant Child's protection for Venice, admirably

depicted in the distance.

Bacchanal of the Andrians (1524)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Bacchanal of the Andrians for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1516 Titian made contact with Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara for

whom he was to work for a decade on pictures destined for the Alabaster

Chamber. In this period he painted a series of magnificent paintings of

Dionysian themes: the Worship of Venus in the Prado, The Andrians

(Bacchanalia), also in the Prado, and Bacchus and Ariadne, in the National

Gallery, London. In these paintings Titian combines a richness of

colouristic expression with a great formal elegance. These are the

elements which characterize this whole so-called "classic" phase of

Titian's development and which is dominated by the supreme masterpiece of

the Frari Assumption of the Virgin.

a high-quality picture of

Bacchanal of the Andrians for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1516 Titian made contact with Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara for

whom he was to work for a decade on pictures destined for the Alabaster

Chamber. In this period he painted a series of magnificent paintings of

Dionysian themes: the Worship of Venus in the Prado, The Andrians

(Bacchanalia), also in the Prado, and Bacchus and Ariadne, in the National

Gallery, London. In these paintings Titian combines a richness of

colouristic expression with a great formal elegance. These are the

elements which characterize this whole so-called "classic" phase of

Titian's development and which is dominated by the supreme masterpiece of

the Frari Assumption of the Virgin.

The Bacchanal of the Andrians was the last in the series, The subjects are taken from classical descriptions of works of art: here Titian reproduces a picture the writer Philostratus saw in Naples in the second century AD, representing the people of the Greek Island of Andros making merry on the river of wine that Dionysus had created. This splendid opportunity to emulate the past was not lost on Titian, whose brilliant naturalism and marvellous colour declare him the equal of Apelles.

The subject of this painting refers to the arrival of Bacchus on the island of Andros, where his followers await him in varying degrees of inebriation, as they drink from the island's river flowing not with water, but with wine. The god himself is not present, but his ship can be glimpsed in the distance and the Bacchanalian essence is exalted in the flask of wine held unsteadily aloft. The shifting shadows may evoke the checkered moods of intemperance, but there is no moral disapproval and the mood is elegiac and tolerant. The choice of subject may reflect not only the hedonism of the patron but also the agricultural prosperity of the Ferrarese countryside, replete with food and drink.

The man leaning on his elbow in the centre derives from Michelangelo's Battle of Cascina cartoon, while the drunken nymph to the far right is based on a classical statue of Ariadne.

Madonna with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family (1526)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family for your computer or notebook. ‣

Titian was neither such a universal scholar as Leonardo, nor such

an outstanding personality as Michelangelo, nor such a versatile and

attractive man as Raphael. He was principally a painter, but a painter

whose handling of paint equaled Michelangelo's mastery of

draughtsmanship. This supreme skill enabled him to disregard all the

time-honored rules of composition, and to rely on color to restore the

unity which he apparently broke up.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family for your computer or notebook. ‣

Titian was neither such a universal scholar as Leonardo, nor such

an outstanding personality as Michelangelo, nor such a versatile and

attractive man as Raphael. He was principally a painter, but a painter

whose handling of paint equaled Michelangelo's mastery of

draughtsmanship. This supreme skill enabled him to disregard all the

time-honored rules of composition, and to rely on color to restore the

unity which he apparently broke up.

We need to look at Madonna with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family which was begun only some fifteen years after Giovanni Bellini's Madonna with Saints to realize the effect which his art must have had on contemporaries. It was almost unheard of to move the Holy Virgin out of the center of the picture, and to place the two administering saints - St. Francis, who is recognizable by the Stigmata (the wounds of the Cross), and St. Peter, who has deposited the key (emblem of his dignity) on the steps of the Virgin's throne - not symmetrically on each side, as Giovanni Bellini had done, but as active participants of a scene.

In this altar-painting, Titian had to revive the tradition of donors' portraits, but did it in an entirely novel way. The picture was intended as a token of thanksgiving for a victory over the Turks by the Venetian nobleman Jacopo Pesaro, and Titian portrayed him kneeling before the Virgin while an armored standard-bearer drags a Turkish prisoner behind him. St. Peter and the Virgin look down on him benignly while St. Francis, on the other side, draws the attention of the Christ Child to the other members of the Pesaro family, who are kneeling in the corner of the picture. The whole scene seems to take place in an open courtyard, with two giant columns which rise into the clouds where two little angels are playfully engaged in raising the Cross.

Titian's contemporaries may well have been amazed at the audacity with which he had dared to upset the old-established rules of composition. They must have expected, at first, to find such a picture lopsided and unbalanced. Actually it is the opposite. The unexpected composition only serves to make it gay and lively without upsetting the harmony of it all. The main reason is the way in which Titian contrived to let light, air and colors unify the scene. The idea of making a mere flag counterbalance the figure of the Holy Virgin would probably have shocked an earlier generation, but this flag, in its rich, warm color, is such a stupendous piece of painting that the venture was a complete success.

Supper at Emmaus (1530)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Supper at Emmaus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting's first owners were the Maffei family from Verona, where

Titian painted an altarpiece for the Cathedral, and its sonorous gravity

and the way the colours traverse the spectrum like a progression of organ

chords may take its tone from nearby Brescia, especially the art of

Moretto. Indeed, Titian may have borrowed the striking orange-yellow of

the page's costume from the similarly placed disciple in Moretto's own

Supper at Emmaus of around 1526, which originally hung in the Church of St

Luke in Brescia and now in the Tosio-Martinengo Museum. The disciple in

green leaning back is modeled on the Judas in Leonardo's Last Supper. The

realism of the still-life is also somewhat in the Lombard taste and

anticipates not only Caravaggio but also the sacramental realism of

Zurbaran.

a high-quality picture of

Supper at Emmaus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting's first owners were the Maffei family from Verona, where

Titian painted an altarpiece for the Cathedral, and its sonorous gravity

and the way the colours traverse the spectrum like a progression of organ

chords may take its tone from nearby Brescia, especially the art of

Moretto. Indeed, Titian may have borrowed the striking orange-yellow of

the page's costume from the similarly placed disciple in Moretto's own

Supper at Emmaus of around 1526, which originally hung in the Church of St

Luke in Brescia and now in the Tosio-Martinengo Museum. The disciple in

green leaning back is modeled on the Judas in Leonardo's Last Supper. The

realism of the still-life is also somewhat in the Lombard taste and

anticipates not only Caravaggio but also the sacramental realism of

Zurbaran.

Madonna and Child with St. Catherine and a Rabbit (1530)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna and Child with St. Catherine and a Rabbit for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1529 Federico Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua ordered three more works from

Titian. The only one to survive is probably identifiable with the Madonna

and Child with St Catherine and a Shepherd, known as the Madonna of the

Rabbit. With a look of winning encouragement the Virgin restrains the

rabbit, a symbol of fecundity, so that the child can clamber down and play

with it. The richly dressed St Catherine, proffering her charge like a

lady-in- waiting, introduces a courtly aspect, and in fact the

Giorgionesque shepherd in the background may be a portrait of Federico

himself: Since x-rays show that the Madonna's head was originally turned

in his direction. In the foreground, the delicate wild flowers recall the

locus amoenus or "idyllic setting" of classical poetry, and in the

park-like landscape we see the Arcadia of the Concert Champutre refracted

through the smiling fertility of the Ferrara Bacchanals. Nowhere else does

Titian so successfully integrate the traditions of the Sacra Conversazione

and the Pastoral.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna and Child with St. Catherine and a Rabbit for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1529 Federico Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua ordered three more works from

Titian. The only one to survive is probably identifiable with the Madonna

and Child with St Catherine and a Shepherd, known as the Madonna of the

Rabbit. With a look of winning encouragement the Virgin restrains the

rabbit, a symbol of fecundity, so that the child can clamber down and play

with it. The richly dressed St Catherine, proffering her charge like a

lady-in- waiting, introduces a courtly aspect, and in fact the

Giorgionesque shepherd in the background may be a portrait of Federico

himself: Since x-rays show that the Madonna's head was originally turned

in his direction. In the foreground, the delicate wild flowers recall the

locus amoenus or "idyllic setting" of classical poetry, and in the

park-like landscape we see the Arcadia of the Concert Champutre refracted

through the smiling fertility of the Ferrara Bacchanals. Nowhere else does

Titian so successfully integrate the traditions of the Sacra Conversazione

and the Pastoral.

This painting mainly captivates through the beauty of its colours and the marvellous landscape. The small format is a sign that this was a private devotional picture. What at first sight appears to be a normal picture of the Madonna gains an additional, very private dimension as a result.

Portrait of Jacopo (Giacomo) Dolfin (Detail) (1532)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Jacopo (Giacomo) Dolfin (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

More than any other sixteenth-century Venetian painter, Titian

understood how to meet the needs of the ruling classes by combining the

demands of likeness with those of social dignity and emotional reserve.

His Portrait of Jacopo (Giacomo) Dolfin - perhaps commissioned to

commemorate the sitter's appointment as provincial governor of the

mainland city of Treviso in 1532 - shows him dressed in his somberly

opulent official crimson robes, and displaying an identifying letter with a

simple gesture of his right hand. His severe and somewhat inscrutable

facial expression is appropriate to a nobleman appointed to weighty

responsibility.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Jacopo (Giacomo) Dolfin (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

More than any other sixteenth-century Venetian painter, Titian

understood how to meet the needs of the ruling classes by combining the

demands of likeness with those of social dignity and emotional reserve.

His Portrait of Jacopo (Giacomo) Dolfin - perhaps commissioned to

commemorate the sitter's appointment as provincial governor of the

mainland city of Treviso in 1532 - shows him dressed in his somberly

opulent official crimson robes, and displaying an identifying letter with a

simple gesture of his right hand. His severe and somewhat inscrutable

facial expression is appropriate to a nobleman appointed to weighty

responsibility.

Annunciation (1535)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Annunciation for your computer or notebook. ‣

The angel in from the left, the hand raised in the gesture of the

annunciation. Under the classical portico the Virgin seems almost

belittled behind the wooden lectern, in a pose of resigned submission to

the will of God. The intimate character of the apparition is underlined by

the presence of everyday objects and animals: the quail, the fruit placed

on the steps of the lectern, the half-open work basket.

a high-quality picture of

Annunciation for your computer or notebook. ‣

The angel in from the left, the hand raised in the gesture of the

annunciation. Under the classical portico the Virgin seems almost

belittled behind the wooden lectern, in a pose of resigned submission to

the will of God. The intimate character of the apparition is underlined by

the presence of everyday objects and animals: the quail, the fruit placed

on the steps of the lectern, the half-open work basket.

This painting was originally placed over one of the arches of the landing of the main staircase which joins the Ground Floor Hall to the Upper Hall of the Scuola.

Titian Art

|

|

More

Articles

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Renaissance

Titian

Art and life.

Early art works by Titian.

Late art works by Titian.

Art

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Della Francesca Art, $19

(95 pictures)

Da Vinci Art, $25

(80 pictures)

Michelangelo Art, $29

(180 pictures)

Raphael Art, $25

(125 pictures)

Titian Art, $29

(175 pictures)

Durer Art, $25

(120 pictures)