Matisse

Simply painting and color

While Matisse was studying under the painter Gustave Moreau, the latter surveyed Matisse's work and commented, both admiringly and prophetically: "You will simplify painting". Then, after a moment's reflection, he added: "But you won't simplify Nature to that extent, to reduce it to that. If you did, painting would no longer exist...", and finally: "Don't listen to me. What you are doing is more important than anything I am telling you. I am a mere teacher, I understand nothing".

Few people ever possessed such insight into Matisse's work. Few

painters have been so misunderstood and treated so unjustly. It began with

his initial Fauvist phase, when his paintings caused an uproar and were

considered to be "a brightly-coloured daub superimposed on what is, after

all, a rather traditional vision - rather like putting up the Christmas

decorations in a drawing-room. Once the celebration is over, the room

returns to its former drabness... Once you remove the 'fauve', all that

remains is the pigeon-fancier". This attitude continued between the Wars,

when Matisse became famous, but was still associated with petty bourgeois

aesthetics, not quite "fashion illustrator" but almost "interior

decorator". "Matisse", commented the critic Pierre Schneider, "is a name

that rhymes with Nice. It evokes balconies overlooking the sun-drenched

Mediterranean, languishing, lazy odalisques, images of luxury,

tranquillity, voluptuousness. In any case, as soon as a painter settles on

the Cote d'Azur his work is immediately considered to be some sort of

summer holiday picture postcard, a sort of perpetual leisure. Matisse:

painter of pleasure, Sultan of the Riviera, an elegant hedonist..."

Few people ever possessed such insight into Matisse's work. Few

painters have been so misunderstood and treated so unjustly. It began with

his initial Fauvist phase, when his paintings caused an uproar and were

considered to be "a brightly-coloured daub superimposed on what is, after

all, a rather traditional vision - rather like putting up the Christmas

decorations in a drawing-room. Once the celebration is over, the room

returns to its former drabness... Once you remove the 'fauve', all that

remains is the pigeon-fancier". This attitude continued between the Wars,

when Matisse became famous, but was still associated with petty bourgeois

aesthetics, not quite "fashion illustrator" but almost "interior

decorator". "Matisse", commented the critic Pierre Schneider, "is a name

that rhymes with Nice. It evokes balconies overlooking the sun-drenched

Mediterranean, languishing, lazy odalisques, images of luxury,

tranquillity, voluptuousness. In any case, as soon as a painter settles on

the Cote d'Azur his work is immediately considered to be some sort of

summer holiday picture postcard, a sort of perpetual leisure. Matisse:

painter of pleasure, Sultan of the Riviera, an elegant hedonist..."

Matisse himself did much to cultivate this upper-class, even professorial, air (his fellow students even nicknamed him "the doctor"). The nickname stuck, a cross between Socrates and Pasteur, and he even bore a physical resemblance to the latter. When, in 1913, Clara MacChesney expressed surprise that such an "abnormal" work of art had been produced by a man who looked so "ordinary and sane", Matisse replied: "Oh, be sure to tell the Americans that I am a normal person, that I am a devoted father and husband, that I have three beautiful children, that I attend the theatre, ride horses, that I have a comfortable home and a beautiful garden I love, with flowers, etc., just like everyone else".

Matisse added with further mockery: "In the same article, the excellent author claims that I do not paint honestly, and I would be justifiably angry had he not taken care to add the afterthought, 'By honestly, I mean by respecting the ideal and the rules.' Unfortunately, he does not let us into the secret of exactly where these rules to which he refers are to be found. I am happy for them to exist and indeed if it were possible to learn them, what sublime artists we would be!"

Matisse did indeed dream of an "art of balance, purity, tranquillity, devoid of disturbing or disquieting subject-matter which will be for everyone who works with his brain, a businessman or a man of letters, for example, a balm, a soothing influence on the mind, something akin to a good armchair which provides relief from bodily fatigue", but he did not do so with impunity. The distance between these words and his being treated as a diehard, out-of-touch reactionary was but a mere step and one more misunderstanding.

Passion

For instance, Matisse hotly disputed Rene Huyghe's

attribution of "an exquisite and refined impassivity". "How can one

practise one's art dispassionately?" he replied. "Without passion, there

is no art. The artist may exercise self-control, to a greater or lesser

extent depending on the case, but it is passion which motivates him.

Anguish? This is no greater today that it was for the Romantics. One must

control all this. One must be calm. Art should neither disquiet nor

trouble - it must be balanced, pure, restful". Matisse confided to Gaston

Diehl: "I have chosen to put torments and anxieties behind me, committing

myself to the transcription of the beauty of the world and the joy of

painting". In 1951, he told old Couturier: "My art is said to come from

the intellect. That is not true; everything I have done, I have done

through passion".

For instance, Matisse hotly disputed Rene Huyghe's

attribution of "an exquisite and refined impassivity". "How can one

practise one's art dispassionately?" he replied. "Without passion, there

is no art. The artist may exercise self-control, to a greater or lesser

extent depending on the case, but it is passion which motivates him.

Anguish? This is no greater today that it was for the Romantics. One must

control all this. One must be calm. Art should neither disquiet nor

trouble - it must be balanced, pure, restful". Matisse confided to Gaston

Diehl: "I have chosen to put torments and anxieties behind me, committing

myself to the transcription of the beauty of the world and the joy of

painting". In 1951, he told old Couturier: "My art is said to come from

the intellect. That is not true; everything I have done, I have done

through passion".

The problem with Matisse is that his painting defies classification, he cannot be slotted neatly into a particular school. Worse still, despite his penchant for discussions of aesthetics and his numerous writings and essays about painting, drawing and colour, he always refused to be a theoretician. He was as wary of his own theories as of the theories of others, and soon distanced himself from the principles or formulas which became the basis for the success of a particular movement or school.

Matisse's painting moves quite freely from one style to another, from an almost naturalist, contoured technique, in which the play of light and shade is translated into classic perspective, to a concept in which large flat areas of colour dispense with volume and offer themselves up for audacious ventures into geometric, even abstract, forms. In actual fact, these are variations on a single theme, in each of which Matisse saw advantages and disadvantages. It is thus almost impossible to divide his work into "periods", that clear segmentation into which a great artist's work is usually split.

The uniqueness of the art of a great painter lies in the fact that he is never satisfied with discoveries which he would be entitled to claim as his own, and immediately launches into new directions. This diversity, which is merely the continuation of a pattern, a springboard, is often disconcerting. In the case of someone like Matisse, who uses all the forms of expression - painting, drawing, sculpture - simultaneously, this creates total confusion. Matisse considered that any means could be used to embrace the form more tightly, to enhance colour and thus offer revolutionary solutions disguised as classical views in the great French pictorial tradition. It is this revolutionary, though seemingly harmless, aspect of his work which is so difficult to decipher. This art of balance, purity and mastery, this "joy of painting the beauty of the universe" which exploded on a world in which the absurd, the disturbing, the "convulsive" reigned supreme.

"I like to model as much as I like to paint", declared Matisse in 1913. "I have no preference. If the quest is the same, when I am tired of one medium, I return to the other - and 'to nourish myself I often make a copy in clay of an anatomical figure... I do so in order to express form, I often devote myself to sculpture which makes it possible for me, instead of just confronting a flat surface, to move around the object and thus get to know it better... But I sculpt like a painter. I do not sculpt like a sculptor. What sculpture has to say is not what music has to say. These are all parallel paths but they cannot be confused with one another..."

Perhaps Matisse's mastery, which is evident from his earliest work, can be explained in part by the fact that he is a rare example of a late developer since there was nothing in his youth or his family background to indicate the route he was to take. Matisse was working as a lawyer's clerk in 1890 when, at the age of 21, he was given a paintbox while recovering from appendicitis. This triggered a sudden and unhesitating change of direction. He abandoned the law for the Academie Julian, where he studied under Bouguereau, the high priest of the "pompiers", the banal but highly popular artists of the time who were so despised by the Impressionists.

Bouguereau reproached Matisse for "not knowing how to draw". "Tired of faithfully reproducing the contours of plaster casts, I went to study under Gabriel Ferrier who taught using live models. I did my utmost to express the feelings which the sight of a woman's body aroused in me". Matisse would find his ideal master in the "charming" Gustave Moreau, a painter whose outlook was broader and who welcomed him into his studio, where he would meet his future companions in the Fauvist venture - Manguin, Camoin, Derain, Marquet and Rouault. "He, at least, was capable of enthusiasm and even of passions".

Andre Marchand reported that in 1947, Matisse said about a landscape which he had painted 40 years earlier. "I was very young, you see, I thought that it was no good, poorly executed, not well-constructed, an insignificant daub, but look at it reduced in the photo; everything is there, it is well-balanced with the tree leaning slightly to the right. Look at this other photo, an enlargement. Basically, all I have done is to develop this idea, you know when one has an idea one is born with it, one develops one's 'idee fixe', one's whole life, one breathes life into it". To other people, he said: "I don't draw any better nowadays, I draw differently". Or: "Not a single attribute of mine is lacking in this picture although they are here in embryonic form".

Matisse's words are applicable to all his early paintings, in which there is really no such thing as the work of a "beginner". From the outset, the composition is in place, colour already emerging in all its splendour. Gustave Moreau, an indulgent, yet excellent critic, commenting on The Dining Table painted in 1897, reveals what is revolutionary in this essay and declares: "Leave it as it is, those carafes are well-balanced on the table and I could hang my hat on the stoppers. That is the main thing". The first Dining Table was exhibited by Matisse at the Salon de la Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts and he was counting on it heavily to make his name. It is an everyday scene of the type he used to paint in his early years, reminiscent of a work by Chardin . There is nothing more traditional than a maid leaning over a set table, arranging flowers in a vase. On the white tablecloth, the well-ordered array of dessert dishes, carafes and crystal glasses create a still life to which the painter has devoted all his skill, so that one can find no fault. But Matisse qua Matisse, is already there - in the white of the tablecloth which is bright but heavily shaded, in the intensity of the splashes of orange and in the carefully studied hues of the shadows. It is there in the "modernist" manner, a la Degas, of representing the scene as if viewed from above, in the Japanese style.

Matisse and Picasso

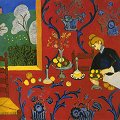

These same elements are expanded upon, simplified of course, and

consequently even more "Matisse" in Harmony in Red - The Red Dining

Table painted in 1908, which hangs in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg.

The scene is obviously exactly the same but this time the colours are no

longer used to add bright touches; they play a much more active role in

relation to each other. This is no longer an intimate household scene, it

is a battle. The window, a constant theme in Matisse's work, has become

the green rectangle of a framed landscape which contrasts with the red

expanse filling the rest of the canvas. In a manner typical of Matisse,

the maid has been turned into a sketch, the array of glasses and bottles

has disappeared. The baroque contortions of the arabesques and garlands

have become all-invading and are now the true subject of the picture. This

essentially graphic theme would appear in all of Matisse's work. It would

return as a leitmotif, as one of the main manifestations of his

personality, as one of his obsessions.

These same elements are expanded upon, simplified of course, and

consequently even more "Matisse" in Harmony in Red - The Red Dining

Table painted in 1908, which hangs in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg.

The scene is obviously exactly the same but this time the colours are no

longer used to add bright touches; they play a much more active role in

relation to each other. This is no longer an intimate household scene, it

is a battle. The window, a constant theme in Matisse's work, has become

the green rectangle of a framed landscape which contrasts with the red

expanse filling the rest of the canvas. In a manner typical of Matisse,

the maid has been turned into a sketch, the array of glasses and bottles

has disappeared. The baroque contortions of the arabesques and garlands

have become all-invading and are now the true subject of the picture. This

essentially graphic theme would appear in all of Matisse's work. It would

return as a leitmotif, as one of the main manifestations of his

personality, as one of his obsessions.

"North Pole, South Pole", is how Picasso - who thought as highly of Matisse's work as the "charming" Moreau did - is said to have defined the contrast between himself and Matisse, the two most illustrious and influential painters of the 20th century. Matisse and Picasso, the two great rivals, in fact, had a relationship which lasted for half a century and which was based on a discreet, almost complicitous, friendship. The one exhalted colour, echoed the other, who smashed form into pieces. "I feel through colour", professed Matisse, "so it is through it that my canvas will always be organised. Yet the feelings ought to be concentrated and the means used brought to their maximum expression".

Fauvism

This passion for colour was to turn Matisse into the reluctant leader

of a school of painting - the Fauves, just as, some 40 years earlier, Manet

had found himself the involuntary leader of the Impressionists. Matisse,

who was supremely reticent by nature, middle-class by habit and totally

opposed to fuss of any kind, found himself promoted to standard-bearer of

the Fauves (a nickname which translated means "wild beasts") and the

number one butt of the critics. At one point, an inscription in chalk, of

which Utrillo was the suspected author, appeared on the walls of

Montparnasse in Paris: "Matisse drives one mad... Matisse is worse than

absinthe".

This passion for colour was to turn Matisse into the reluctant leader

of a school of painting - the Fauves, just as, some 40 years earlier, Manet

had found himself the involuntary leader of the Impressionists. Matisse,

who was supremely reticent by nature, middle-class by habit and totally

opposed to fuss of any kind, found himself promoted to standard-bearer of

the Fauves (a nickname which translated means "wild beasts") and the

number one butt of the critics. At one point, an inscription in chalk, of

which Utrillo was the suspected author, appeared on the walls of

Montparnasse in Paris: "Matisse drives one mad... Matisse is worse than

absinthe".

Surely this wild beast, this "Fauve", contrary to what he was considered to be in his day, was a gentle lamb or, rather, a sort of benevolent psychiatrist determined to cure our ills. The way in which Matisse translated this heavenly happiness through his use of intense colours must indicate that Matisse was no "Fauve", if being a Fauve implies violence, since his colour scheme belongs to light and is non-violent by nature. Colour had been a revelation to Matisse from the outset, and he now sought how best to control it totally, to allow it to explode freely all over the canvas in joyous proliferation. As the forerunner of the Minimalists, Matisse was attempting to "simplify painting" just as his teacher, Gustave Moreau, had predicted and he now sought to reduce it to the essentials - the minimum of resources used to produce the maximum results. In this respect, he is both the precursor and the accomplice of all the simplifiers of our time, from Malevich to Mondrian.

One of the stages in this final conquest of colour was Matisse's encounter with Signac, with whom he spent the summer of 1904 at Saint-Tropez. The flamboyant colours and brilliant light with which the Midi is so generously endowed hastened this development. Matisse first experienced the shock of Mediterranean light after a short trip with his wife Amelie to London, where he discovered Turner. It was in the South of France that he found his true climate, the one to which he would remain faithful his whole life, the reflection of the sun "in his belly" as Picasso put it.

Signac's Pointillist technique, which made the colours sing on the canvas and impregnated them with light in a continual play of scintillating reflections, was to be used in a painting which marks a turning-point in the history of modern art, a painting which Matisse contemplated long and hard and which was preceded by numerous sketches and preparatory studies. This was Luxe, Calme et Volupte completed in 1905 and exhibited in the spring of the following year at the Salon des Independants.

Matisse put his all into this painting, using his skill and talent to the utmost. The composition was undoubtedly inspired by the Cezanne painting which Matisse owned, and in fact he first called it Bathers, in homage to the original model. But there is also something of Poussin in this work, especially the position of the semi-reclining nude in the foreground; it may be based on the Bacchanale in the Louvre which Matisse had once copied.

Signac and Cross applauded the performance and enjoyed the strong and dominant contrasts. Yet Cross accurately predicted: "It is good, but you will not remain with it..." In fact, the techniques of Seurat, Signac and company did not completely satisfy Matisse who disassociated himself from them, making the cogent point: "Postimpressionism, or rather the offshoot called Divisionism, was the first attempt to order the techniques of Impressionism, but the process was an ordering of a purely physical nature, a medium which was often mechanical and which corresponded to purely physical emotion. The fragmentation of colour caused a fragmentation of form and shape. Result: a disjointed surface. There is a retinal sensation but it destroys the tranquillity of surface and form. Objects are only differentiated by the degree of luminosity allotted to them. Everything is treated in the same way. In the end, there is mere tactile animation, comparable to a 'vibrato' of the voice or the violin... I have not kept to this path; I have painted in large expanses seeking the quality of the painting through a harmony between the flat expanses of colour. I have tried to replace the 'vibrato' by a more expressive, more direct harmony, a harmony whose simplicity and sincerity would enable me to achieve calmer surfaces". Matisse concluded with this damning condemnation: "Fauvism dislodged the tyranny of Divisionism. One cannot live in a household that is too orderly, a home run by aunts from the provinces. So off one goes into the bush, to seek simpler methods which do not smother the spirit. In this instance, the influence of Gauguin and Van Gogh are also evident. These are the ideas of their time: construction through coloured surfaces, experimenting with the intensity of colour, the subject matter being unimportant, reaction against the diffusion of localised hues into the light. The light is not removed but is expressed through the harmony of brightly-coloured surfaces".

It was in Gauguin's technique of expanses of colour, that Matisse discovered the instrument of his release from Pointillism. To the future Fauves, van Gogh contributed his dynamism and his ability to translate his feelings into colour. Gauguin contributed his synthesised, intellectual art. Vlaminck expressed it as "The art of van Gogh is human, sensitive, lively; that of Gauguin is cerebral, intellectual, stylised". So it was not difficult to sense which direction each of those embarking on the Fauvist adventure would lean to, and sometimes take, and how the two currents of which Fauvism consisted would establish themselves. On the one hand there were the intellectuals - Matisse, Marquet, Friesz, Dufy and Braque - who were influenced by Gauguin. On the other, there were the primitives - Vlaminck, Derain, van Dongen - who were influenced by van Gogh. The division was not inviolable, of course; for instance, Derain stayed at Collioure in 1905 with Matisse and his work evolved into a decorative style using expanses of colour like Gauguin. Matisse, on the other hand, was by no means indifferent to van Gogh's art and frequently imitated his short brushstrokes.

Wassily Kandinsky, whose book On the Spiritual in Art, published in 1912, constitutes the fundamental theory of abstract art and contrasted the two artists: "Matisse: colour, Picasso: form. Two great tendencies, one great goal".

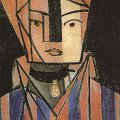

Although he kept himself at a distance, Matisse also played a role in the creation of Cubism which was to displace Fauvism. It was he who initiated Picasso into African art (I'art negre) of which he was a collector and of which there are traces in such paintings as Blue Nude, Standing Nude or Nude in Pink Slippers. Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) was painted at Collioure after a trip to Algeria. The only sign of the location are the palm-trees in the background, while the nude is inspired by the reclining figure in Luxe, Calme et Volupte and La Joie de Vivre. In this painting, he plays with the volume of the female form, emphasized by the flatness of the background, a thick shadow separating the two worlds.

"What interests me most", he would say, "is not the still life nor the landscape either. It is the human figure. This is what makes it possible for me to best express the almost religious feeling which I have about life". In the case of both Matisse and Picasso, one is at a transitional stage, what Alfred Barr called "Cezanne or the crisis of 1907-1908", which affected everyone, not only the Fauves, but Matisse, Detain, Dufy, Vlaminck and even Picasso. It was the period when, for example, Braque moved straight from Fauvism to Cubism without a transition.

This "crise cezanienne" which Matisse and Picasso experienced for various reasons, drew on such fertile soil that the two contrasting styles were both able to feed from it. The style chosen by Picasso gave rise to Cubism. The other, Matisse's choice, evolved into a more synthesised construct, using larger and larger expanses of flat colour and a tendency towards geometric shapes, so that his art ceased to be subservient to emotion in order to become one of contemplation. However, a faint hint of Fauvism was to linger permanently in the background.

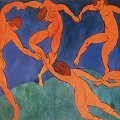

Two years after the scandal sparked off by the 1905 Salon d'Automne, Fauvism's destiny was fulfilled. In its two or three years of existence, it had helped to show young painters one of the ways in which it was possible to achieve the freedom of expression which lies behind the achievements of modern art. Each of the Fauves then went his own way, but the lesson they had imparted, as a group, in such a short space of time, left deep impressions which can be found among the German Expressionists, the Russian painters such as Malevich and Kandinsky, in Soutine, in Klein, in Tapies and right up to certain currents of American abstract art of the post-World War II period, as well as in some less prominent movements such as "Support-Surface" in France, that is to say, among all those who believed or who still believe in the opportunities afforded by colour. As Matisse said to Georges Duthuit: "Fauvism is not everything but it is the foundation of everything". Jean Leymarie noted that with Lajoiede Vivre, Matisse had succeeded in surpassing the traditional opposition between Ingres and Delacroix, the Western alternative that assigns line to the intellect and colour to the emotions. This Matisse victory is by no means the least of his revolutions.

Colors

"If Cezanne was right, I am right", Matisse would reassure himself,

determined to discover the secret of his art. "In moments of doubt", he

explained in 1925 to Jacques Guenne, "when I was still seeking myself,

sometimes frightened by my discoveries, I knew that Cezanne had not been

mistaken. You see, in Cezanne's work there are laws of architecture which

are very useful to a young painter. Of all the great painters, he had the

merit of wanting - giving his work as a painter its greatest mission -

shades of colour to be the strength of a painting. It is hardly surprising

that Cezanne hesitated for so long and so constantly. Personally, each

time I stand in front of my canvas, it seems as though I am painting for

the first time. There were so many possibilities in Cezanne who, more than

anyone else, felt the need for an orderly mind. Cezanne, you see, is a

sort of God of painting. Is his influence dangerous? What if it is! So much

for those who are not strong enough to be able to withstand it! Not to be

robust enough to be able to sustain an influence without weakening is

proof of impotence".

"If Cezanne was right, I am right", Matisse would reassure himself,

determined to discover the secret of his art. "In moments of doubt", he

explained in 1925 to Jacques Guenne, "when I was still seeking myself,

sometimes frightened by my discoveries, I knew that Cezanne had not been

mistaken. You see, in Cezanne's work there are laws of architecture which

are very useful to a young painter. Of all the great painters, he had the

merit of wanting - giving his work as a painter its greatest mission -

shades of colour to be the strength of a painting. It is hardly surprising

that Cezanne hesitated for so long and so constantly. Personally, each

time I stand in front of my canvas, it seems as though I am painting for

the first time. There were so many possibilities in Cezanne who, more than

anyone else, felt the need for an orderly mind. Cezanne, you see, is a

sort of God of painting. Is his influence dangerous? What if it is! So much

for those who are not strong enough to be able to withstand it! Not to be

robust enough to be able to sustain an influence without weakening is

proof of impotence".

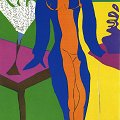

"Let colours be the forces in a painting..." All of Matisse's work, from start to finish, is a record of artistic duality. The phenomenon is particularly evident in the confrontation between shape and colour in the two versions of the Sailor. Yet this art still appears to be based on the equivocal and the implied. Such confrontations can also be diversified and change their nature. Is there a painter in the history of Western Art, who has produced more delightful, impromptu and amusing variations on the theme of duality as has Matisse? Is there a painter who leaves so much to the viewer to fathom his most mysterious messages?

This is where the difference lies between a Matisse painting and any other object. One can love - or hate - the former without penetrating the miracles of refinement, the fertility of invention, the often dissimulated depth of technique, implied by this elliptical method so full of allusions which are the only way in which the painter can demonstrate his extraordinary gifts. His talents are as extensive as they are original and they are the result of a dual attribute. On the one hand, there is his amazing sense of the rhythm of line, a rhythm which is both continuous and incredibly flexible, that is capable of abandoning itself to the strangest variations without ever breaking its continuity and thus giving itself the ability to follow the theme throughout its meanderings. On the other hand, this infallible feeling for the harmony of colour which is not content with a complete accord but which constantly adds an element of surprise, an unexpected juxtaposition, causing one to exclaim: "Where on earth did he find this color which happens to be so exactly right!"

Quotes by Matisse

- Why have I never been bored? For more than fifty years I have never ceased to work.

- When I put a green, it it not grass. When I put a blue, it is not the sky.

- Would not it be best to leave room to mystery?

- Expression, for me, does not reside in passions glowing in a human face or manifested by violent movement. The entire arrangement of my picture is expressive; the place occupied by the figures, the empty spaces around them, the proportions, everything has its share.

- I do not literally paint that table, but the emotion it produces upon me.

- Cutting into color reminds me of the sculptor's direct carving.

- Seek the strongest color effect possible... the content is of no importance.

- In modern art, it is undoubtedly to Cezanne that I owe the most.

- The essential thing is to spring forth, to express the bolt of lightning one senses upon contact with a thing. The function of the artist is not to translate an observation but to express the shock of the object on his nature; the shock, with the original reaction.

- It has bothered me all my life that I do not paint like everybody else.

- Creativity takes courage.

- It is not enough to place colors, however beautiful, one beside the other; colors must also react on one another. Otherwise, you have cacophony.

- Impressionism is the newspaper of the soul.

Henri Matisse Art

|

|

More

Articles

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Modernism

Henri Matisse

Life and work.

The Music. The Dance.

Simply painting and color.

Paper cutouts.

Art

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Munch Art, $19

(75 pictures)

Malevich Art, $25

(105 pictures)

Modigliani Art, $29

(135 pictures)

Klee Art, $25

(150 pictures)

Miro Art, $35

(150 pictures)

Matisse Art, $29

(180 pictures)

Picasso Art, $29

(175 pictures)

Dali Art, $35

(275 pictures)

Chagall Art, $35

(175 pictures)