Salvador Dali

Salvador Dali, one of the greatest Spanish

painters of all time, and one of the most important figures in the

history of Modernism. Both Dali's extraordinary

talent and odd personality helped him to rise above the rest of the

Surrealists of the 20th century. His artwork and influences can be

seen almost everywhere around the world. His explicit and

controversial Surrealist paintings are some of the most famous, and

infamous, paintings of the 1900's, and his rebellious and independent

attitude towards art and politics set him aside from other painters,

leaving a mark on Surrealist painting forever. Dali expressed

surrealism in everything he said and did. He was not just

unconventional and dramatic; he was fantastic, shocking, and

outrageous. Salvador Dali remains one of the great artistic innovators

of all time. Like Picasso,

Matisse, Miro and

Chagall, his place at the pinnacle of modern

art history is assured.

Salvador Dali, one of the greatest Spanish

painters of all time, and one of the most important figures in the

history of Modernism. Both Dali's extraordinary

talent and odd personality helped him to rise above the rest of the

Surrealists of the 20th century. His artwork and influences can be

seen almost everywhere around the world. His explicit and

controversial Surrealist paintings are some of the most famous, and

infamous, paintings of the 1900's, and his rebellious and independent

attitude towards art and politics set him aside from other painters,

leaving a mark on Surrealist painting forever. Dali expressed

surrealism in everything he said and did. He was not just

unconventional and dramatic; he was fantastic, shocking, and

outrageous. Salvador Dali remains one of the great artistic innovators

of all time. Like Picasso,

Matisse, Miro and

Chagall, his place at the pinnacle of modern

art history is assured.

Surreal

Salvador Dali (1929 - 1941)

> analysis of art, paintings, and works...

- The Great Masturbator (1929)

- Illumined Pleasures (1929)

- The Invisible Man (1929)

- Portrait of Paul Eluard (1929)

- Invisible Sleeping Woman (1930)

- The Dream (1931)

- Le Spectre et le Fantome (1931)

- The Persistence of Memory (1931)

- Shades of Night Descending (1931)

- Gradiva Finds the Anthropomorphic Ruins (1931)

- They Were There (1931)

- Eggs on the Plate Without the Plate (1932)

- Angelus (1932)

- The Dream Approaches (1933)

- The Architectural Angelus of Millet (1933)

- Gala and the Angelus of Millet Preceding the Imminent Arrival of the Conical Anamorphoses (1933)

- Necrophilic Fountain Flowing from a Grand Piano (1933)

- The Triangular Hour (1933)

- Enigmatic Elements in the Landscape (1934)

- Masochistic Instrument (1934)

- Moment of Transition (1934)

- The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition (1934)

- The Angelus of Gala (1935)

- Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's Angelus (1935)

- Paranoiac-Critical Solitude (1935)

- The Horseman of Death (1935)

- The Anthropomorphic Cabinet (1936)

- Autumn Cannibalism (1936)

- Sun Table (1936)

- The Burning Giraffe (1937)

- The Invention of the Monsters (1937)

- Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937)

- Sleep (1937)

- Swans Reflecting Elephants (1937)

- The Endless Enigma (1938)

- Impressions of Africa (1938)

- Spain (1938)

- The Enigma of Hitler (1939)

- Philosopher Illuminated by the Light of the Moon and the Setting Sun (1939)

- Daddy Longlegs of the Evening... Hope! (1940)

- Old Age, Adolescence, Infancy (The Three Ages) (1940)

- Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire (1940)

- Two Pieces of Bread, Expressing the Sentiment of Love (1940)

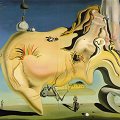

The Great Masturbator (1929)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Great Masturbator for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Great Masturbator is a self-portrait painted in July

1929. Dali's head has the shape of a rock formation near his home and

is seen in this form in several paintings dating from 1929. The

painting deals with Dali's fear and loathing of sex. He blamed his

negative feelings toward sex as partly a result of reading his

father's, extremely graphic book on venereal diseases as a young

boy.

a high-quality picture of

The Great Masturbator for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Great Masturbator is a self-portrait painted in July

1929. Dali's head has the shape of a rock formation near his home and

is seen in this form in several paintings dating from 1929. The

painting deals with Dali's fear and loathing of sex. He blamed his

negative feelings toward sex as partly a result of reading his

father's, extremely graphic book on venereal diseases as a young

boy.

The head is painted "soft", as if malleable to the touch; it looks fatigued, sexually spent: the eyes are closed, the cheeks flushed. Under the nose a grasshopper clings, its abdomen covered with ants that crawl onto the face where a mouth should be. From early childhood, Dali had a phobia of grasshoppers and the appearance of one here suggests his feelings of hysterical fear and a loss of voice or control.

Emerging from the right of the head, a woman moves her mouth toward a man's crotch. The man's legs are cut and bleeding, implying a fear of castration. The woman's face is cracked, as though the image that Dali's head produces will soon disintegrate. To reiterate the sexual theme, the stamen of a lily and tongue of a lion appear underneath the couple.

Illumined Pleasures (1929)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Illumined Pleasures for your computer or notebook. ‣

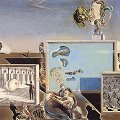

Illumined Pleasures was created by fusing oil and collage

on panel. The canvas of the painting is small, measuring only 10" x

14" (24 x 34.5 cm); its size compared with the mass of detail Dali has

managed to cram into it, clearly reveals Dali's great talent as a

miniaturist painter.

a high-quality picture of

Illumined Pleasures for your computer or notebook. ‣

Illumined Pleasures was created by fusing oil and collage

on panel. The canvas of the painting is small, measuring only 10" x

14" (24 x 34.5 cm); its size compared with the mass of detail Dali has

managed to cram into it, clearly reveals Dali's great talent as a

miniaturist painter.

Other Surrealist artists, in both paintings and objects, had made use of boxes. Here Dali uses them to create scenarios - pictures within the main picture. In the middle box is a self-portrait, like that of The Great Masturbator. Blood flows out of the nose and above the head is a grasshopper: both symbolise an hysterical fear. The box to the left shows a man shooting at a rock. This rock can be construed as a head, with blood flowing from the holes. The box to the right has a pattern of men on cycles with sugared almonds placed on their heads.

The painting has a chaotic, frenzied energy; it is filled with violent images. In the foreground, a couple is struggling. The woman's hands are covered in blood as she grasps at a swirl of a blue that emanates from the self-portrait, as if trying to catch the essence of Dali.

The Invisible Man (1929)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Invisible Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

Though begun in 1929, The Invisible Man was not completed

until 1932. It was the first painting in which Dali began to use the

double images that were to flood his work over the next decade,

during his "paranoia-critical" period. The double images used here are

not as successful as the later painting, Swans Reflecting

Elephants (1937). The viewer is aware of the illusions that Dali

is creating before they are aware of what the overall form is meant

to be.

a high-quality picture of

The Invisible Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

Though begun in 1929, The Invisible Man was not completed

until 1932. It was the first painting in which Dali began to use the

double images that were to flood his work over the next decade,

during his "paranoia-critical" period. The double images used here are

not as successful as the later painting, Swans Reflecting

Elephants (1937). The viewer is aware of the illusions that Dali

is creating before they are aware of what the overall form is meant

to be.

The yellow clouds become the man's hair; his lace and upper torso are formed by ruined architecture that is scattered in the landscape and a waterfall creates the vague outline of his legs. As with almost all Dali's work in 1929, this painting deals with his fear of sex. The recurring image of the "jug woman" appears on the left of the picture. To the right of her is an object with a womb shape, part of which delineates the right arm of the man. The dark shape outlining the fingers and legs of the man suggests the female form. Beneath the man a wild beast is prowling - another of Dali's recurring sexual symbols.

Portrait of Paul Eluard (1929)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Paul Eluard for your computer or notebook. ‣

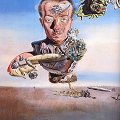

This portrait dates from the same year as The Great

Masturbator and shares the same themes of sexual frustration and

fear. Although it is a portrait, the painting tells us more of Dali's

emotional state at this time than that of the subject, Paul Eluard,

who was a French poet of the Surrealist movement. Together with his

wife Gala, Eluard visited Dali at Cadaques during the summer of 1929.

Dali and Gala fell in love, beginning their fifty-year

relationship.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Paul Eluard for your computer or notebook. ‣

This portrait dates from the same year as The Great

Masturbator and shares the same themes of sexual frustration and

fear. Although it is a portrait, the painting tells us more of Dali's

emotional state at this time than that of the subject, Paul Eluard,

who was a French poet of the Surrealist movement. Together with his

wife Gala, Eluard visited Dali at Cadaques during the summer of 1929.

Dali and Gala fell in love, beginning their fifty-year

relationship.

The bust of Eluard hovers over a bleak landscape. From the right of his head a lion appears. This features heavily in Dali's work during 1929-1930 - he defined the head as symbolic of his fear of sexual performance with a woman; he was a virgin when he met Gala. The lion's head often appears, as it does here, next to a woman's head which is shaped as a jug. Dali's Freudian interpretation of the lion leads us to see the jug/woman as a vessel that eagerly waits to be filled; she grins at the lion lasciviously. On the left, Dali has placed a self-portrait with a grasshopper across his face; to the artist the grasshopper represented hysterical fear and disgust.

Invisible Sleeping Woman (1930)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Invisible Sleeping Woman for your computer or notebook. ‣

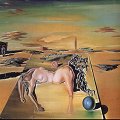

This analytical work is one of the first painted in the new house

in Port Lligat during the summer Of 1930. In his numerous written

works Dali has given us much information about this picture. "A month

after my return from Paris," he writes, "I signed a contract with

George Keller and Pierre Colle. Shortly after in the latter's gallery

I exhibited my Invisible Sleeping Woman, Horse, Lion, fruit of

my contemplation at Cape Creus." The Viscount of Noailles bought this

oil. Invisible Sleeping Woman, Horse, Lion must be considered

the most important painting after The Invisible Man among

Dali's early experiments with double images. The permanent theme

which predominates over all the others is that of the persistence of

desires.

a high-quality picture of

Invisible Sleeping Woman for your computer or notebook. ‣

This analytical work is one of the first painted in the new house

in Port Lligat during the summer Of 1930. In his numerous written

works Dali has given us much information about this picture. "A month

after my return from Paris," he writes, "I signed a contract with

George Keller and Pierre Colle. Shortly after in the latter's gallery

I exhibited my Invisible Sleeping Woman, Horse, Lion, fruit of

my contemplation at Cape Creus." The Viscount of Noailles bought this

oil. Invisible Sleeping Woman, Horse, Lion must be considered

the most important painting after The Invisible Man among

Dali's early experiments with double images. The permanent theme

which predominates over all the others is that of the persistence of

desires.

Speaking of this picture, Dali has given a definition: "The double image (the example of which may be that of the image of the horse alone which is at the same time the image of a woman) can be prolonged, continuing the paranoiac process, the existence of another obsessive idea being then sufficient to make a third image appear (the image of a lion, for example) and so forth, until the concurrence of a number of images, limited only by the degree of the capacity for paranoiac thought." The violently erotic character of the group of fellateurs metamorphosed into the forelegs and the head of the horse is veiled by the immutable aspect of the ensemble, obtained with the help of an absence of dense shadows and violent colors, as well as by the geological character of the forms. Dali said of these models: "They are always boats which seem to be drawn by exhausted fishermen, by fossil fishermen."

Dali painted three pictures of the same subject with different titles. One of the three was destroyed during the demonstrations which broke out when the film L'Age dor was being shown at Studio 28 in Paris on December 3, 1930.

The Dream (1931)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Dream for your computer or notebook. ‣

By the Thirties, Surrealist painting had moved toward the arena of

dreams for inspiration and relied less on the ideas of automatism

that had marked the beginning of the movement. The Dream was

painted in 1931 but the main image, the woman's head, had first

appeared the year before in The Fountain, where, although in

the background, it was a striking and dominant feature. Dali found

the inspiration for the woman from a scene on a box and a monument in

Barcelona.

a high-quality picture of

The Dream for your computer or notebook. ‣

By the Thirties, Surrealist painting had moved toward the arena of

dreams for inspiration and relied less on the ideas of automatism

that had marked the beginning of the movement. The Dream was

painted in 1931 but the main image, the woman's head, had first

appeared the year before in The Fountain, where, although in

the background, it was a striking and dominant feature. Dali found

the inspiration for the woman from a scene on a box and a monument in

Barcelona.

In the foreground of this dark painting is the bust of a woman, painted in dull, metallic grays, her hair floating above her as if frozen in movement. The colors used and her apparent immobility bring to mind the Classical myth of Medusa. The woman has no mouth and her eyes also appear sealed shut, like those of the giant head in Sleep. The absence of a mouth, together with the seeming immobility of the woman implies a loss of control, of paralysis. Ants crawl across the face in the place where a mouth should be. As a child, Dali had found a pet bat crawling with ants and so, for him, they became symbols of death and decay.

Le Spectre et le Fantome (1931)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Le Spectre et le Fantome for your computer or notebook. ‣

Le Spectre et le Fantome - the spectre and the phantom - is

one of a series of paintings that shared a theme of spectral and

phantom appearances. In a letter to the French Surrealist poet Paul

Eluard, Dali defined the clouds and the rainbow as being the spectre

and the brick shape as being the phantom. The clouds take on forms as

the viewer stares at them, reflecting the basis of Dali's

paranoia-critical method.

a high-quality picture of

Le Spectre et le Fantome for your computer or notebook. ‣

Le Spectre et le Fantome - the spectre and the phantom - is

one of a series of paintings that shared a theme of spectral and

phantom appearances. In a letter to the French Surrealist poet Paul

Eluard, Dali defined the clouds and the rainbow as being the spectre

and the brick shape as being the phantom. The clouds take on forms as

the viewer stares at them, reflecting the basis of Dali's

paranoia-critical method.

The work has the same female figure as Mediumistic-Paranoaic Image. The woman is in the foreground, sitting in a puddle on a beach. She is a combination of Dali's nurse, his friend Lidia and another of Dali's obsessions from that time which was to cause him trouble in the future: Hitler. His obsession with Hitler was partly caused by what he called the "soft flesh" of his back, which was tightly held in by his uniform. He dreamt of him as a wet nurse sitting knitting in a puddle. The woman in the painting has a small cut taken out of her back that emphasizes this obsession with "Hitlerian" flesh.

The Persistence of Memory (1931)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Persistence of Memory for your computer or notebook. ‣

Many of Dali's paintings were influenced and inspired by the

landscapes of his youth. Several in particular were painted on the

slopes of Mount Pani, which was covered in beautiful umbrella pines

at the time. Many of the strange and foreboding shadows in the

foreground of many Dali paintings is a direct reference to and result

of Dali's love of this mountain near his home. Even long after he had

grown up, Dali continued to paint details of the landscape of

Catalonia into his works, as evidenced by such works as The

Persistence of Memory, completed in 1931.

a high-quality picture of

The Persistence of Memory for your computer or notebook. ‣

Many of Dali's paintings were influenced and inspired by the

landscapes of his youth. Several in particular were painted on the

slopes of Mount Pani, which was covered in beautiful umbrella pines

at the time. Many of the strange and foreboding shadows in the

foreground of many Dali paintings is a direct reference to and result

of Dali's love of this mountain near his home. Even long after he had

grown up, Dali continued to paint details of the landscape of

Catalonia into his works, as evidenced by such works as The

Persistence of Memory, completed in 1931.

Note the craggy rocks of Cape Creus in the background to the right. One of Dali's most memorable Surrealist works, indeed the one with which he is most often associated is The Persistence of Memory. It shows a typical Dalinian landscape, with the rocks of his beloved Cape Creus jutting up in the background. In the foreground, a sort of amorphous self portrait of Dali seems to melt. Three Separate Melting Watch images even out the foreground of the work. The melting watches are one symbol that is commonly associated with Salvador Dali's Surrealism. They are literally meant to show the irrelevance of time.

When Dali was alone with Gala and his paintings in Cape Creus, he felt that time had little, perhaps no significance for him. His days were spent eating, painting, making love, and anything else he wanted to do. The warm, summery days seemed to fly by without any real indication of having passed.

One hot August afternoon, in 1931, as Dali sat at his work bench nibbling at his lunch, he came upon one of his most stunning paranoiac-critical hallucinations. Upon taking a pencil, and sliding it under a bit of Camembert cheese, which had become softer and runnier than usual in the summer heat, Dali was inspired with the idea for the melting watches. They appear often throughout Dali's works, and are the subject of much interest. In short, this particular work, is an important referral back to Dali's Catalan Heritage, that was so very important to him.

Shades of Night Descending (1931)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Shades of Night Descending for your computer or notebook. ‣

The obsessive character of this work is made evident by one of the

less important elements and the least noticed by the viewer: the

measureless shadow which is spread out in the bottom part of the

canvas. Its obsessional power is obtained by having in the center a

rock whose shadow is much less dense that that of the one in the

foreground. In appearance this reef seems to be a rock like the

others; however, it is already constructed in such a way that its

shadow bears a resemblance, due to its design, to the one in the

foreground. Their source is moreover quite different, and it is there

that the painter has successfully applied his famous

paranoiac-critical method.

a high-quality picture of

Shades of Night Descending for your computer or notebook. ‣

The obsessive character of this work is made evident by one of the

less important elements and the least noticed by the viewer: the

measureless shadow which is spread out in the bottom part of the

canvas. Its obsessional power is obtained by having in the center a

rock whose shadow is much less dense that that of the one in the

foreground. In appearance this reef seems to be a rock like the

others; however, it is already constructed in such a way that its

shadow bears a resemblance, due to its design, to the one in the

foreground. Their source is moreover quite different, and it is there

that the painter has successfully applied his famous

paranoiac-critical method.

The shadow in the foreground is that of a concert grand piano, an instrument which holds a predominant place in many of Dali's Surrealist compositions, such as Diurnal Illusion: the Shadow of a Grand Piano Approaching, 1931; Average Bureaucrat; Six apparitions of Lenin on a Grand Piano, 1931; or Myself at the Age of Ten When I Was a Grasshopper Child, 1933. This piano is "the one that belonged to the Pichots with its shadows," Dali relates; "I was impressed by these shadows in the setting sun, near the tall cypress in the interior court of the house, and another time when they had brought the instrument onto the rocks beside the water." The spectral victory standing in the lower-right corner of the picture is concealing heteroclite objects, half-hidden under the drapery in whose tortured folds the figure is wrapped. Two of these things, a glass and a shoe, are used with the same impact to stretch out the skin on the back of the figure in Diurnal Illusion. Speaking of his fetishism, Dali has said, "It was a question of all the fetishes and slippers of my childhood fossilized underneath the membranes of my anguish, all mimetized at Cap Creus." Shoe fetishes appear often in scenes of "bureaucratic cannibalism," where one can see the most varied figures: a girl, Nietzche, or Maxim Gorky devouring a high-heeled shoe.

Gradiva Finds the Anthropomorphic Ruins (1931)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Gradiva Finds the Anthropomorphic Ruins for your computer or notebook. ‣

Gradiva Finds the Ruins of Anthropomorphis was based on a

German story, analyzed by Freud, of an archeologist who falls in love

with Gradiva, a girl he sees in a Greek stone relief. He later finds

his true love, who is the reincarnation of Gradiva. The Surrealists

took this myth for their own. For them, Gradiva meant "she who

advances", a woman who would lead to self-discovery. To Dali, Gradiva

was Gala, the realization of his fictional past loves and his muse.

a high-quality picture of

Gradiva Finds the Anthropomorphic Ruins for your computer or notebook. ‣

Gradiva Finds the Ruins of Anthropomorphis was based on a

German story, analyzed by Freud, of an archeologist who falls in love

with Gradiva, a girl he sees in a Greek stone relief. He later finds

his true love, who is the reincarnation of Gradiva. The Surrealists

took this myth for their own. For them, Gradiva meant "she who

advances", a woman who would lead to self-discovery. To Dali, Gradiva

was Gala, the realization of his fictional past loves and his muse.

In Gradiva Finds the Ruins, Dali plays with the story of Gradiva. Set against a flat, dark landscape, she is in the foreground with her arms wrapped around a human shape that is made from stone, (Anthropomorphis). Parts of the figure are cracked and there are holes where the face, heart and genitals should be, implying that this creature is without any of the parts that constitute a human. The form of Anthropomorphis is similar to that of a figure, which can be interpreted as Dali, in the painting Solitude (1931). The figure has a Dalinian inkwell on his shoulder and as Gradiva appears as Gala, the implication here is that Dali is Anthropomorphis.

They Were There (1931)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

They Were There for your computer or notebook. ‣

Dali had many different ways of signing a painting; sometimes

using an emblem or a crown. They Were There is signed "Gala

Dali"; he had begun signing his work with both his and Galas names in

1931. Dali said that this was because it was mostly with Gala's blood

that he painted. The signature on this painting was made with

blood-red paint to emphasize this point.

a high-quality picture of

They Were There for your computer or notebook. ‣

Dali had many different ways of signing a painting; sometimes

using an emblem or a crown. They Were There is signed "Gala

Dali"; he had begun signing his work with both his and Galas names in

1931. Dali said that this was because it was mostly with Gala's blood

that he painted. The signature on this painting was made with

blood-red paint to emphasize this point.

They Were There is a portrait, though the subject is unknown. The man stands in the foreground staring straight out at the viewer, which was unusual for Dali's portraits. He appears relaxed with one hand in the pocket of his casual suit, a cigarette in the other hand. The background of the painting is the usual desert, bounded by green hills. The man on the rearing horse is an image also seen in Mme. Reese. They Were There does not show Dali's usual eye for the miniature details, the trees in the background are basic and little effort seems to have been taken over the clouds either. In both Mme. Reese and They Were There the brushwork on the people is very smooth; there are no wrinkles or lines, giving an almost plastic quality.

Eggs on the Plate Without the Plate (1932)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Eggs on the Plate Without the Plate for your computer or notebook. ‣

Dali tells us that this work was inspired by an intra-uterine

memory. He says that one day, after vigorously rubbing his eyes, he

became fascinated with the brilliant yellow, orange, and ochre colors

he saw. As a result, he says, he had a flashback to his mother's

womb, and created this paranoiac-critical explanation of the

experience.

a high-quality picture of

Eggs on the Plate Without the Plate for your computer or notebook. ‣

Dali tells us that this work was inspired by an intra-uterine

memory. He says that one day, after vigorously rubbing his eyes, he

became fascinated with the brilliant yellow, orange, and ochre colors

he saw. As a result, he says, he had a flashback to his mother's

womb, and created this paranoiac-critical explanation of the

experience.

Suspended on a string, in the center of the work is a single egg yolk, which Dali said represented himself in the womb. Below that, the two eggs on the plate (curious, that plate, look at the title again) were painted with a shimmering yolk. These represented the piercing gaze of Gala Dali, whom Dali had met in 1929. At the time, she had been the darling of the Surrealist movement, not to mention the wife of Paul Eluard, the French poet. It was said that her gaze could pierce through walls, and Dali is paying her homage here.

A large, cubist building dominates the scene, while other objects are attached to the wall facing the eggs. First is a small, dripping watch, a continuation of the theme of the melting watches done in The Persistence of Memory. Above that is a phallic ear of corn, representing male sexuality. Just to the left of the ear of corn is a window in the building, and standing in it, looking out through another window, are the father and son figures that were originally painted in The First Days of Spring, some three years ago. Off in the distance are the rocks of Dali's homeland.

Angelus (1932)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Angelus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The True Picture of the "Island of the Dead" by Arnold Bocklin

at the Hour of the Angelus is Dali's reworking of the German

painter Arnold Bocklin's piece, Island of the Dead; Dali was

writing a study on Bocklin during this period. Bocklin said that the

Island of the Dead was a painting "to dream over",

deliberately leaving it untitled so that the meaning remained open to

interpretation by the viewer. Bocklin's thoughts were very close to

views held by the Surrealists, especially Dali. On the left appear

the only objects: a cup with a thin rod attached to it sitting on a

block. Using Freudian dream interpretation (which is evident

throughout Dali's early work) any receptacle is female and any rod is

regarded as phallic. Read as male and female, these objects could be

the reason for Dali's inclusion of the "Angelus" in the title.

a high-quality picture of

Angelus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The True Picture of the "Island of the Dead" by Arnold Bocklin

at the Hour of the Angelus is Dali's reworking of the German

painter Arnold Bocklin's piece, Island of the Dead; Dali was

writing a study on Bocklin during this period. Bocklin said that the

Island of the Dead was a painting "to dream over",

deliberately leaving it untitled so that the meaning remained open to

interpretation by the viewer. Bocklin's thoughts were very close to

views held by the Surrealists, especially Dali. On the left appear

the only objects: a cup with a thin rod attached to it sitting on a

block. Using Freudian dream interpretation (which is evident

throughout Dali's early work) any receptacle is female and any rod is

regarded as phallic. Read as male and female, these objects could be

the reason for Dali's inclusion of the "Angelus" in the title.

The island does not resemble the island in the Bocklin painting; it resembles more the shape of the head in Paranoiac Face, painted around the same time. It is probable that both of these paintings were based upon the same rocky, coastal scenery.

The Dream Approaches (1933)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Dream Approaches for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Dream Approaches has the haunting atmosphere of a

dream, aided by a luminescent pre-dawn sky. In the foreground of the

painting is a potentially coffin-shaped form, over which white

material is draped. On the right side of this block is a large cocoon

shape, its opening suggesting the female genitalia. Standing on the

sandy beach is a naked man, Classical in form as well as stance, with

one hand raised and his hips tilted. The brushwork on his body

creates the illusion that dark flames are swirling along his back.

a high-quality picture of

The Dream Approaches for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Dream Approaches has the haunting atmosphere of a

dream, aided by a luminescent pre-dawn sky. In the foreground of the

painting is a potentially coffin-shaped form, over which white

material is draped. On the right side of this block is a large cocoon

shape, its opening suggesting the female genitalia. Standing on the

sandy beach is a naked man, Classical in form as well as stance, with

one hand raised and his hips tilted. The brushwork on his body

creates the illusion that dark flames are swirling along his back.

On the right, next to two trees that are still half in darkness, is a tall tower with one solitary window at the top. The tower seems like a ruin as the plaster is falling away and there are cracks along it. Amongst other paintings, this tower can also be seen in The Horseman of Death (1934). Towers appear in Dali's work as a symbol of desire and death. In his autobiographical writings, Dali explained this as owing to his childhood memories of a mill tower, where he had felt both sexual and violent urges toward a girl.

The Architectural Angelus of Millet (1933)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Architectural Angelus of Millet for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Architectonic Angelus of Millet shows how Dali used the

"paranoia-critical" method, employing Millet's The Angelus as

the catalyst. Dali saw a reproduction of The Angelus in 1929,

not having thought about it since childhood. He had been obsessed

with the image as a child, finding parallels between that and two

cypress trees that stood outside his classroom. Upon seeing this

reproduction, he became very upset and distressed; to discover why he

employed psychoanalytical methods. He also began to see The

Angelus in "visions" in objects around him: once in a lithograph

of cherries, once in two stones on a beach. The Architectonic

Angelus of Millet was based upon this latter "vision".

a high-quality picture of

The Architectural Angelus of Millet for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Architectonic Angelus of Millet shows how Dali used the

"paranoia-critical" method, employing Millet's The Angelus as

the catalyst. Dali saw a reproduction of The Angelus in 1929,

not having thought about it since childhood. He had been obsessed

with the image as a child, finding parallels between that and two

cypress trees that stood outside his classroom. Upon seeing this

reproduction, he became very upset and distressed; to discover why he

employed psychoanalytical methods. He also began to see The

Angelus in "visions" in objects around him: once in a lithograph

of cherries, once in two stones on a beach. The Architectonic

Angelus of Millet was based upon this latter "vision".

Unlike Gala and The Angelus of Millet, The Architectonic Angelus has no reproduction of The Angelus. Instead, the Angelus couple are transformed into two huge, white stones that loom over the Catalonian landscape. Dali pointed out that although the male stone on the left appears to be dominant due to its size, the female stone is the aggressor here, pushing out a part of herself to make physical contact with the male. The often-used image of the young Dali with his father can be seen sheltering underneath the male stone.

Gala and the Angelus of Millet Preceding the Imminent Arrival of the Conical Anamorphoses (1933)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Gala and the Angelus of Millet Preceding the Imminent Arrival of the Conical Anamorphoses for your computer or notebook. ‣

In this interior scene reproduced here in nearly actual size, Dali

has brought together some of the characters or the obsessional themes

of his Surrealist works before 1935. In the background, Gala, smiling,

contemplates the scene; she is dressed in a richly embroidered jacket

and is wearing a white cap with a transparent yellow-green visor which

was then ih style. The seated figure facing her, one hand placed on

the table near a ball and a precariously balanced cube, is easily

recognizable: it is Lenin. On the left, the indiscrete mustachioed man

eavesdropping behind the door is Maxim Gorky; on his head there is a

lobster, a crustacean that the painter often places in equally

anachronistic spots, even creating in 1936 an object known as the

"lobster-telephone." Along with the soft watches, one of the most

persistent obsessive images in Dali's works is undoubtedly The

Angelus of Jean-Francois Millet, painter of the peasant world.

a high-quality picture of

Gala and the Angelus of Millet Preceding the Imminent Arrival of the Conical Anamorphoses for your computer or notebook. ‣

In this interior scene reproduced here in nearly actual size, Dali

has brought together some of the characters or the obsessional themes

of his Surrealist works before 1935. In the background, Gala, smiling,

contemplates the scene; she is dressed in a richly embroidered jacket

and is wearing a white cap with a transparent yellow-green visor which

was then ih style. The seated figure facing her, one hand placed on

the table near a ball and a precariously balanced cube, is easily

recognizable: it is Lenin. On the left, the indiscrete mustachioed man

eavesdropping behind the door is Maxim Gorky; on his head there is a

lobster, a crustacean that the painter often places in equally

anachronistic spots, even creating in 1936 an object known as the

"lobster-telephone." Along with the soft watches, one of the most

persistent obsessive images in Dali's works is undoubtedly The

Angelus of Jean-Francois Millet, painter of the peasant world.

This picture, which is in the Louvre in Paris, is reproduced in Dali's painting hung over the door. Dali attributes to this image an erotic significance explained in his book, Le Mythe tragique de L'Angelus de Millet, in which he describes in minute detail and at great length this delirious phenomenon. "In June 1932, there suddenly came to my mind without any close or conscious association, which would have provided an immediate explanation, the image of The Angelus of Millet. This image consisted of a visual representation which was very clear and in colors. It was nearly instantaneous and was not followed by other images. It made a very great impression on me, and was most upsetting to me because, although in my vision of the afore-mentioned image everything corresponded exactly to the reproductions of the picture with which I was familiar, it appeared to me nevertheless absolutely modified and charged with such latent intentionality that The Angelus of Millet Suddenly' became for me the pictorial work which was the most troubling, the most enigmatic, the most dense and the richest in unconscious thoughts that I had ever seen."

Necrophilic Fountain Flowing from a Grand Piano (1933)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Necrophilic Fountain Flowing from a Grand Piano for your computer or notebook. ‣

Necrophilic Spring Flowing from a Grand Piano shows one of

the many appearances that grand pianos make in Dali's work during the

Thirties. Dali explained their Surrealistic appearance on the beaches

or plains in his paintings, as a sight he had seen in reality: the

Pitchot family, who were close friends of the Dalis, performed

outdoor concerts, sometimes going to the extent of bringing a grand

piano with them.

a high-quality picture of

Necrophilic Fountain Flowing from a Grand Piano for your computer or notebook. ‣

Necrophilic Spring Flowing from a Grand Piano shows one of

the many appearances that grand pianos make in Dali's work during the

Thirties. Dali explained their Surrealistic appearance on the beaches

or plains in his paintings, as a sight he had seen in reality: the

Pitchot family, who were close friends of the Dalis, performed

outdoor concerts, sometimes going to the extent of bringing a grand

piano with them.

The piano has a puddle-shaped hole in the middle of its back, out of which a cypress tree grows. Cypress trees often appear in Dali's paintings of the Thirties, for example in The Dream Approaches (1932). These trees reminded Dali of the Pitchot estate, where he would spend long, happy hours in erotic daydreams.

The word "necrophilic" in the title recalls Dali's neurotic fears that penetrative sex would lead to his death. The hole in the piano seems reflective as if filled with water; it is the origin of the "necrophilic spring". From the middle of the piano underneath the keys, the spring flows into a piano-shaped hole in the ground. This hole insinuates a grave and death, so that the spring has become a necrophiliac.

The Triangular Hour (1933)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Triangular Hour for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Triangular Hour was painted using oil on canvas. After

their first appearance in The Persistence of Memory (1933),

Dali's "soft watches" were to become a regular image throughout his

work.

a high-quality picture of

The Triangular Hour for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Triangular Hour was painted using oil on canvas. After

their first appearance in The Persistence of Memory (1933),

Dali's "soft watches" were to become a regular image throughout his

work.

The watch in The Triangular Hour differs from other "soft watches" in that it has no metal casing. In addition it appears to be actually made from stone; it has a crack across its face that is similar to the cracks in the rock that it is placed on. It also does not appear as melted, as "soft", as other watches seen in earlier paintings; here it is merely misshapen.

The watch is mounted on a rock formation as if hung on a kitchen wall. Underneath is a hole in the rock through which we see an Ampordan plain, where the figure of a child with a hoop can be seen. At the top of the rock formation is the bust of a Classical man, his face in a grimace. Dali has placed rocks on top of the bust, as well as on top of the rock formation and on the other rock in the shadowy foreground. One interpretation of this painting is that Dali is viewing mankind and time as governed by the solidity of nature.

Enigmatic Elements in the Landscape (1934)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Enigmatic Elements in the Landscape for your computer or notebook. ‣

This composition is entirely imaginary. It was painted in Paris in

1934 in the apartment that Dali and Gala occupied on the first floor

at 88 rue de l'Universite. The artist at work, pictured in the

foreground seated in front of his easel, is Vermeer of Delft

contemplating the wide plain of Ampurdan. Farther back one sees Dali

as a child in his sailor's suit holding his hoop and standing beside

his nurse of the type that he called Hitlerian nurses, much to the

great fury of the Surrealists; still farther back two soft forms are

coupled - they constitute part of that series of forms, erotic in

character, used by Dali during his Surrealist period which he called

"symbols" and of which he gave the following definition in the

Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism: "Morphological,

sub-cutaneous concretion, symbolic of hierarchies." At the lower

right two little fragments appear splashed with the morning light. A

silhouette, inexplicably and equivocally draped, rises up in front of

a row of cypress trees - those that Dali used to see through the

window in the courtyard of his school in Figueras; the lower is

reminiscent of the one on the Pichots' property, called the

Mill-Tower, near his birthplace; and behind this is a bell-tower

typical of Catalonian churches.

a high-quality picture of

Enigmatic Elements in the Landscape for your computer or notebook. ‣

This composition is entirely imaginary. It was painted in Paris in

1934 in the apartment that Dali and Gala occupied on the first floor

at 88 rue de l'Universite. The artist at work, pictured in the

foreground seated in front of his easel, is Vermeer of Delft

contemplating the wide plain of Ampurdan. Farther back one sees Dali

as a child in his sailor's suit holding his hoop and standing beside

his nurse of the type that he called Hitlerian nurses, much to the

great fury of the Surrealists; still farther back two soft forms are

coupled - they constitute part of that series of forms, erotic in

character, used by Dali during his Surrealist period which he called

"symbols" and of which he gave the following definition in the

Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism: "Morphological,

sub-cutaneous concretion, symbolic of hierarchies." At the lower

right two little fragments appear splashed with the morning light. A

silhouette, inexplicably and equivocally draped, rises up in front of

a row of cypress trees - those that Dali used to see through the

window in the courtyard of his school in Figueras; the lower is

reminiscent of the one on the Pichots' property, called the

Mill-Tower, near his birthplace; and behind this is a bell-tower

typical of Catalonian churches.

The owner, Mr. Cyrus Sulzberger, considers this picture a real good-luck charm. As a young man, he bought it while visiting the 32nd International Exhibition of Art at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh in 1934, paying for it in installments of five dollars a week. Later he was forced to part with it. Only a few years ago (around 1991), he was able to convince its owner to sell him this painting, without which he could not get along.

Masochistic Instrument (1934)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Masochistic Instrument for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Masochistic Instrument interprets a childhood scene in

which Dali manipulated a female fruit-picker into climbing up a

ladder placed outside his room in order for her breasts and torso to

be framed by his window.

a high-quality picture of

Masochistic Instrument for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Masochistic Instrument interprets a childhood scene in

which Dali manipulated a female fruit-picker into climbing up a

ladder placed outside his room in order for her breasts and torso to

be framed by his window.

The viewer's eye is led to the naked woman by the insinuation of the angles that are created between the sloping roof beneath the window and the blue of the sky. The paleness of the woman's skin is highlighted by the use of shadow and by the contrasting, vividly colored walls of the house in which she stands. Her face can not be seen, lending an air of mystery to the piece. In her hand she holds a violin between two fingers as if in disgust. She looks ready to throw the fatigued violin away. It is "soft" and distorted like the cello seen in Daddy Longlegs of the Evening...Hope! (1940). The shape of the violin repeats the female form, but here the inference is that the violin should be read as a phallic object. The erect pole with a piece of cloth flowing from the end of it attached to the tree can also be read as phallic.

Moment of Transition (1934)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Moment of Transition for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Moment of Transition was painted in 1934. On the left,

a woman dressed entirely in white, the material flowing behind her,

stands facing the cart. The image of the woman in white is repeated

in several of Dali's paintings, either directly or suggestively. In

Gradiva Finds the Ruins of Anthropomorphis the woman's shape

is implied by the shape of the white rocks in the background. This

woman was Dali's first cousin, Carolinetta, who died aged seventeen

from consumption, when Dali was still a child.

a high-quality picture of

Moment of Transition for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Moment of Transition was painted in 1934. On the left,

a woman dressed entirely in white, the material flowing behind her,

stands facing the cart. The image of the woman in white is repeated

in several of Dali's paintings, either directly or suggestively. In

Gradiva Finds the Ruins of Anthropomorphis the woman's shape

is implied by the shape of the white rocks in the background. This

woman was Dali's first cousin, Carolinetta, who died aged seventeen

from consumption, when Dali was still a child.

The cart in the painting looks like a hollowed-out bone. On first glance the cart has two people in it, but upon closer inspection, the people take on the form of a building in the town it approaches and the rear end of a horse.

The Moment of Transition continues the theme of Dali's painting The Phantom Wagon (1933) in which the same cart, landscape, and visual illusion are shown. In the latter painting, however, the cart appears at a further distance from the town that it heads for. As we see the cart in closer detail in The Moment of Transition Dali's visual illusion becomes more apparent, explaining the title of the work.

The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition (1934)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition for your computer or notebook. ‣

The center portion of this painting shows Dali's aging nurse Lucia

sitting with her back to us, in the position of a netmender.

Netmending was an important task in the Catalan fishing villages of

Dali's youth, and he associates that importance with Lucia. The hole

cut from her back is a paranoiac-critical transformation whose

original inspiration came from Dali's visit to Paris in 1928. There

he visited the Hotel of the Invalids, which sported windows made from

mannequins with holes cut into their mid-riffs. He transforms them

into the seated Lucia here, who is also shown being propped up by a

crutch, here a symbol of solemnity, a wish by Dali to support her as

she grows older.

a high-quality picture of

The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition for your computer or notebook. ‣

The center portion of this painting shows Dali's aging nurse Lucia

sitting with her back to us, in the position of a netmender.

Netmending was an important task in the Catalan fishing villages of

Dali's youth, and he associates that importance with Lucia. The hole

cut from her back is a paranoiac-critical transformation whose

original inspiration came from Dali's visit to Paris in 1928. There

he visited the Hotel of the Invalids, which sported windows made from

mannequins with holes cut into their mid-riffs. He transforms them

into the seated Lucia here, who is also shown being propped up by a

crutch, here a symbol of solemnity, a wish by Dali to support her as

she grows older.

Next to Lucia, to her right, are a medicine table and bottle, supposedly the 'object' that has been removed from Lucia's back. Next to that is another smaller chest and bottle, these having been removed from the first.

To Lucia's left are 4 fishing boats which have been pulled up onto the shoreline. As is suggested by both Lucia's netmending, and the boats themselves, fishing was of paramount importance to the Catalonians on the coastline. Despite the craggy rocks and treacherous currents, fish had always been a staple in Dali's time. Farther off in the distance are a building and then the unique stepped hills of the Coasta Brava.

This work is actually very small in person, like many of the oil on panel paintings that Dali was doing at the time. It is reported that some of these were fashioned by Dali's use of a single horsehair for a brush, creating intricate levels of detail. When viewed in person, one can actually see the individual brush strokes in this work, which imparts a new sense of respect for Dali's still blooming talents.

The Angelus of Gala (1935)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Angelus of Gala for your computer or notebook. ‣

Out of the series of paintings using the theme of Millet's The

Angelus, this painting portrays the emotional fears that the

painting aroused in Dali the most effectively. In The Secret Life

of Salvador Dali, Dali writes that he saw The Angelus,

which to most people is a religious work showing humble folk praying,

as a "monstrous example of disguised sexual repression".

a high-quality picture of

The Angelus of Gala for your computer or notebook. ‣

Out of the series of paintings using the theme of Millet's The

Angelus, this painting portrays the emotional fears that the

painting aroused in Dali the most effectively. In The Secret Life

of Salvador Dali, Dali writes that he saw The Angelus,

which to most people is a religious work showing humble folk praying,

as a "monstrous example of disguised sexual repression".

The Angelus of Gala contains two versions of The Angelus: the first is the unusual portrait of a double Gala, the second is the copy of The Angelus above Gala's head. The Gala that we see here is, unusually, unattractive; her mouth clenches tightly together, her eyes stare aggressively at her double. Looking at the reproduction of The Angelus above Gala, the female perches on the wheelbarrow, as does the main figure. The female in The Angelus is sexually aggressive; like a praying mantis, ready to devour her mate after receiving the attention that she hunts for. This explains the fierce look on Gala's face as she stares at her double, who is the male counterpart to her female "Angelus".

Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's Angelus (1935)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's Angelus for your computer or notebook. ‣

Millet's Angelus painting had a profound impact on Salvador Dali.

He had first seen the work as a child in school, but in 1932, he has

a series of experiences that led him to have several

paranoiac-critical transformations on the subject. The original

painting shows several peasants, working in a field, who have stopped

for an afternoon prayer. Their heads are bowed reverently, and there

is a wheelbarrow between them, with field scenery stretching out

behind them.

a high-quality picture of

Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's Angelus for your computer or notebook. ‣

Millet's Angelus painting had a profound impact on Salvador Dali.

He had first seen the work as a child in school, but in 1932, he has

a series of experiences that led him to have several

paranoiac-critical transformations on the subject. The original

painting shows several peasants, working in a field, who have stopped

for an afternoon prayer. Their heads are bowed reverently, and there

is a wheelbarrow between them, with field scenery stretching out

behind them.

This painting is a continuation on that theme, but has several instances of Dalinian continuity included as well. The original two Angelus figures have been transformed into towering architectural ruins, which probably were inspired by Dali's visits to the Roman ruins near his childhood home. The third figure of the dead son is absent in this rendition of Dali's obsession with the original Millet painting. Instead, the female has been made to look even more like a praying mantis, thus reinforcing Dali's association of sex with death. Dali spent time on the plain of Ampurdan, and has added elements from that landscape into this one.

In the foreground, however, is another example of Dalinian continuity. Here we see yet again the tiny father/son figure that began to show up in Dali's works starting in 1929 with The First Days of Spring.

Paranoiac-Critical Solitude (1935)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Paranoiac-Critical Solitude for your computer or notebook. ‣

During 1935 and 1936, Dali's repetition and use of elements which

are completely out of place is remarkable. Here the desired effect is

obtained with the maximum of force, and the minimum of means. Dali

has taken a small piece of desolate landscape with some rocks. Into

his decor, he has placed an automobile, or rather a wreck of an

automobile - like those of Hibert-Robert - overgrown and half-covered

with flowering plants, and then has incorporated the machine into the

rocky crags, through which a hole has been pierced. Next, in a

paranoiac manner, he has divided the image in two by repeating it on

the left part of the rock while scrupulously re-creating the

silhouette of the vehicle, impressed in the hollow of the rock, of

which a piece, cut out in the same shape as the hole on the right,

appears suspended in front. The optical uneasiness of this picture

stems from the contradiction which exists between the piece of rock

on the left in relief and the empty space in the rock on the right,

which itself seems clearly in front of the car. Here in Dali's

research into dividing, one realizes how the stereoscopic phenomenon

has always interested him in a continuos way, because it is

definitely a question of the stereoscopic effect applied to the

problem of the dream in colors and relief. In this work, it is also

possible to understand the desire of the painter who is always

looking for examples in natural phenomena to explain certain

scientific laws, affirming that one day we will undoubtedly find in

geology traces of holograms, while today that possibility remains

quite out of the question in the minds of the specialists.

Paranoiac-Critical Solitude was painted on olive wood in Port

Lligat.

a high-quality picture of

Paranoiac-Critical Solitude for your computer or notebook. ‣

During 1935 and 1936, Dali's repetition and use of elements which

are completely out of place is remarkable. Here the desired effect is

obtained with the maximum of force, and the minimum of means. Dali

has taken a small piece of desolate landscape with some rocks. Into

his decor, he has placed an automobile, or rather a wreck of an

automobile - like those of Hibert-Robert - overgrown and half-covered

with flowering plants, and then has incorporated the machine into the

rocky crags, through which a hole has been pierced. Next, in a

paranoiac manner, he has divided the image in two by repeating it on

the left part of the rock while scrupulously re-creating the

silhouette of the vehicle, impressed in the hollow of the rock, of

which a piece, cut out in the same shape as the hole on the right,

appears suspended in front. The optical uneasiness of this picture

stems from the contradiction which exists between the piece of rock

on the left in relief and the empty space in the rock on the right,

which itself seems clearly in front of the car. Here in Dali's

research into dividing, one realizes how the stereoscopic phenomenon

has always interested him in a continuos way, because it is

definitely a question of the stereoscopic effect applied to the

problem of the dream in colors and relief. In this work, it is also

possible to understand the desire of the painter who is always

looking for examples in natural phenomena to explain certain

scientific laws, affirming that one day we will undoubtedly find in

geology traces of holograms, while today that possibility remains

quite out of the question in the minds of the specialists.

Paranoiac-Critical Solitude was painted on olive wood in Port

Lligat.

The Horseman of Death (1935)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Horseman of Death for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Horseman of Death shares images from several of Dali's

works dating from this time. The rainbow set against dense clouds is

an image that Dali also used in Le Spectre et le Fantome. Dali

interpreted this combined image as a representation of the spectre

from the title of the painting. The tower in the background can also

be seen in several other paintings, such as The Dream

Approaches. Dali explained that the significance of this tower

was a sexual one, as it was an image that formed the background to

many of his long, erotic daydreams. A dense cluster of cypress trees

hides the tower from our view. The cypress tree is also a familiar

image in Dali's paintings of the early to mid Thirties, their

significance, once again, having roots in Dali's childhood memories.

The horseman itself is a frequent image, although here he is in a

state of disintegration, parts of his horse still has flesh

remaining, while the horseman is purely skeleton.

a high-quality picture of

The Horseman of Death for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Horseman of Death shares images from several of Dali's

works dating from this time. The rainbow set against dense clouds is

an image that Dali also used in Le Spectre et le Fantome. Dali

interpreted this combined image as a representation of the spectre

from the title of the painting. The tower in the background can also

be seen in several other paintings, such as The Dream

Approaches. Dali explained that the significance of this tower

was a sexual one, as it was an image that formed the background to

many of his long, erotic daydreams. A dense cluster of cypress trees

hides the tower from our view. The cypress tree is also a familiar

image in Dali's paintings of the early to mid Thirties, their

significance, once again, having roots in Dali's childhood memories.

The horseman itself is a frequent image, although here he is in a

state of disintegration, parts of his horse still has flesh

remaining, while the horseman is purely skeleton.

Dali wrote of this piece that it reminded him, with a sense of deja vu, of the interior of the Island of the Dead by Bocklin.

The Anthropomorphic Cabinet (1936)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Anthropomorphic Cabinet for your computer or notebook. ‣

From Dali's work, figures with drawers are almost as well known to

the public as his "soft watches", particularly his sculpture Venus

de Milo with Drawers. In order to paint this figure of a woman

half-lying on the ground, Dali did several very elaborate preliminary

drawings in pencil and in ink. They were all executed at Edward

James's residence in London, where Dali was living. It is probably

there that he began the picture. Anthropomorphic Cabinet was

exhibited, for the first time, in London in 1936 at the Lefevre

Gallery. Dali, who had been a great admirer of Freud for many years,

purposely wished to depict here in images the psychoanalytical

theories of the great Viennese professor, saying apropos these

subjects that "they are kinds of allegories destined to illustrate a

certain complacency, to smell the innumerable narcissistic odors

emanating from each one of our drawers," and more precisely later,

"The unique difference between immortal Greece and the contemporary

epoch is Sigmund Freud, who discovered that the human body, which was

purely neo-platonian at the time of the Greeks, is today full of

secret drawers that only psychoanalysis is capable of opening." The

furniture-figures of the seventeenth-century Italian mannerist

Bracelli were known by Dali and undoubtedly influenced his figures

with drawers, but what was only a game and a geometric exercise in

space to the first artist became to the second one, three centuries

later, an allegorical representation charged with the great

obsessional power of our will to know who we are.

a high-quality picture of

The Anthropomorphic Cabinet for your computer or notebook. ‣

From Dali's work, figures with drawers are almost as well known to

the public as his "soft watches", particularly his sculpture Venus

de Milo with Drawers. In order to paint this figure of a woman

half-lying on the ground, Dali did several very elaborate preliminary

drawings in pencil and in ink. They were all executed at Edward

James's residence in London, where Dali was living. It is probably

there that he began the picture. Anthropomorphic Cabinet was

exhibited, for the first time, in London in 1936 at the Lefevre

Gallery. Dali, who had been a great admirer of Freud for many years,

purposely wished to depict here in images the psychoanalytical

theories of the great Viennese professor, saying apropos these

subjects that "they are kinds of allegories destined to illustrate a

certain complacency, to smell the innumerable narcissistic odors

emanating from each one of our drawers," and more precisely later,

"The unique difference between immortal Greece and the contemporary

epoch is Sigmund Freud, who discovered that the human body, which was

purely neo-platonian at the time of the Greeks, is today full of

secret drawers that only psychoanalysis is capable of opening." The

furniture-figures of the seventeenth-century Italian mannerist

Bracelli were known by Dali and undoubtedly influenced his figures

with drawers, but what was only a game and a geometric exercise in

space to the first artist became to the second one, three centuries

later, an allegorical representation charged with the great

obsessional power of our will to know who we are.

Autumn Cannibalism (1936)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Autumn Cannibalism for your computer or notebook. ‣

As with many artists, Dali was to depict war and conflict in

several of his major works. Autumn Cannibalism was painted in

1936, the year the civil war began in Spain. The painting is an

evocative interpretation of the horror and destruction of war, and

also comments on the devoring nature of sexual relationships.

a high-quality picture of

Autumn Cannibalism for your computer or notebook. ‣

As with many artists, Dali was to depict war and conflict in

several of his major works. Autumn Cannibalism was painted in

1936, the year the civil war began in Spain. The painting is an

evocative interpretation of the horror and destruction of war, and

also comments on the devoring nature of sexual relationships.

On a chest of drawers placed on a Catalonian beach sit the top halves of two people. They are so entangled that the viewer has to look carefully to see which arm belongs to which figure. One figure holds a fork pointed to the other one's head, while it dips a spoon into the malleable flesh. A languid hand holds a gleaming knife that has sliced into the soft flesh of the other. Their featureless heads merge into each other, their individuality becoming indistinguishable.

Pieces of meat are draped about the painting, symbolizing death. The meat also alludes to the temporary nature of life and to the bestial nature of human beings. On one head is an apple, which to Dali represented a struggle between father and son, (the son being the apple, the father William Tell), and beneath the figures is a peeled apple, symbolizing the destruction of the son.

Sun Table (1936)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Sun Table for your computer or notebook. ‣

Salvador Dali's greatest intellectual and artistic honesty is

probably never to have practiced any sophisticated, gymnastic

aesthetics, in order to place the most disparate and most bizarre

objects in his pictures. Sun Table is a good example of this.

When he painted this composition, Dali did not know why he put a

camel in with all the other elements which belonged to Cadaques. Today

he explains the premonitional character of this image by pointing out

the package of Camel cigarettes placed at the feet of the silhouette

of the young boy, probably himself, and he told me in 1970 that he

had read an article by Martin Gardner which appeared in the magazine

Scientific American under the heading "scientific games," in

which the author explained that "the image on the cover of a package

of cigarettes was full of extraordinary objective hazards - for

example, the English word 'choice' written vertically in capital

letters on the side of the package, when looked at in a mirror,

remains unchanged and perfectly legible." In order to stress the

out-of-context and obsessive character of a camel with all the

magical aspects associated with the animal, Dali wrote later in his

book Dix recettes d'immortalite that "seen through an

electronic microscope it is possible to demonstrate that a camel is

much less precise than a cloud." The table in the middle of the

picture is a table from the cafe Le Casino in Cadaques, on which are

placed one duro and three glasses, the same glasses in which today is

still served tallat, the Catalonian coffee with cream. The

tiled floor is what was being put in Dali's kitchen at the time that

he was painting this picture, having installed himself at a

glass-topped table in the dining room of the house in Port Lligat.

a high-quality picture of

Sun Table for your computer or notebook. ‣

Salvador Dali's greatest intellectual and artistic honesty is

probably never to have practiced any sophisticated, gymnastic

aesthetics, in order to place the most disparate and most bizarre

objects in his pictures. Sun Table is a good example of this.

When he painted this composition, Dali did not know why he put a

camel in with all the other elements which belonged to Cadaques. Today

he explains the premonitional character of this image by pointing out

the package of Camel cigarettes placed at the feet of the silhouette

of the young boy, probably himself, and he told me in 1970 that he

had read an article by Martin Gardner which appeared in the magazine

Scientific American under the heading "scientific games," in

which the author explained that "the image on the cover of a package

of cigarettes was full of extraordinary objective hazards - for

example, the English word 'choice' written vertically in capital

letters on the side of the package, when looked at in a mirror,

remains unchanged and perfectly legible." In order to stress the

out-of-context and obsessive character of a camel with all the

magical aspects associated with the animal, Dali wrote later in his

book Dix recettes d'immortalite that "seen through an

electronic microscope it is possible to demonstrate that a camel is

much less precise than a cloud." The table in the middle of the

picture is a table from the cafe Le Casino in Cadaques, on which are

placed one duro and three glasses, the same glasses in which today is

still served tallat, the Catalonian coffee with cream. The

tiled floor is what was being put in Dali's kitchen at the time that

he was painting this picture, having installed himself at a

glass-topped table in the dining room of the house in Port Lligat.

The Burning Giraffe (1937)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Burning Giraffe for your computer or notebook. ‣

Dali believed that both The Burning Giraffe and The

Invention of Monsters were premonitions of war. Both of these

paintings contain the image of a giraffe with its back ablaze, an

image which Dali interpreted as "the masculine cosmic apocalyptic

monster". He first used this image of the giraffe in flames in his

film L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age) in 1930.

a high-quality picture of

The Burning Giraffe for your computer or notebook. ‣

Dali believed that both The Burning Giraffe and The

Invention of Monsters were premonitions of war. Both of these

paintings contain the image of a giraffe with its back ablaze, an

image which Dali interpreted as "the masculine cosmic apocalyptic

monster". He first used this image of the giraffe in flames in his

film L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age) in 1930.

The Burning Giraffe appears as very much a dreamscape, not simply because of the subject but also because of the supernatural aquamarine color of the background. Against this vivid blue color, the flames on the giraffe stand out to great effect.

In the foreground, a woman stands with her arms outstretched. Her forearms and face are blood red, having been stripped to show the muscle beneath the flesh. The woman's face is featureless now, indicating a nightmarish helplessness and a loss of individuality. Behind her, a second woman holds aloft a strip of meat, representing death, entrophy, and the human races capacity to devour and destroy. The women both have elongated phallic shapes growing out from their backs, and these are propped up with crutches - Dali repeatedly uses this symbolism for a weak and flawed society.

The Invention of the Monsters (1937)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Invention of the Monsters for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Invention of the Monsters is part of a series of works

that one might term as tumultuous, painted by Dali between 1935 and

1940; the most important among them are Impressions of Africa;

Soft Construction with Boiled Beans: Premonition of Civil War; and

Autumn Cannibalism. These three paintings reflect the troubled

times before World War II. In the book Dali de Gala, the

painter has written about the Premonition of Civil War and

Autumn Cannibalism: "These Iberian people devouring each other

in autumn express the pathos of civil war thought of a phenomenon of

natural history." In The Invention of the Monsters, Dali has

painted his premonition of World War II. Dali began the picture in

1937, in Paris, in his studio on rue de la Tombe-Issoire and resumed

work on it at the winter-sports resort of Semmering, south of Vienna.

When Dali learned that the Art Institute of Chicago had acquired this

work, he sent a telegram with the following explanation: "Am happy

and honored by your acquisition. According to Nostradamus, the

apparition of monsters is a presage of war. This canvas was painted

in the mountains of Semmering a few months before the Anschluss and it

has a prophetic character. The women-horses represent the maternal

river-monsters, the flaming giraffe the male cosmic apocalyptic

monster. The angel-cat is the divine heterosexual monster, the

hour-glass the metaphysical monster. Gala and Dali together the

sentimental monster. The little lonely blue dog is not a true

monster." The theme of the women-horses that one sees here in a herd

bathing in a pond is the same as in Invisible Sleeping Woman,

Horse, Lion. Here the shapes have changed completely: three years

later they will give birth to a series of pictures entitled The

Marsupial Centaurs. About the double figure seen in the

foreground, holding a butterfly and an hourglass in his hands, the

painter has stated precisely that it was the Pre-Raphaelite result of

the double portrait of Dali and Gala painted right behind it.

a high-quality picture of

The Invention of the Monsters for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Invention of the Monsters is part of a series of works

that one might term as tumultuous, painted by Dali between 1935 and

1940; the most important among them are Impressions of Africa;

Soft Construction with Boiled Beans: Premonition of Civil War; and

Autumn Cannibalism. These three paintings reflect the troubled

times before World War II. In the book Dali de Gala, the

painter has written about the Premonition of Civil War and

Autumn Cannibalism: "These Iberian people devouring each other

in autumn express the pathos of civil war thought of a phenomenon of

natural history." In The Invention of the Monsters, Dali has

painted his premonition of World War II. Dali began the picture in

1937, in Paris, in his studio on rue de la Tombe-Issoire and resumed

work on it at the winter-sports resort of Semmering, south of Vienna.

When Dali learned that the Art Institute of Chicago had acquired this

work, he sent a telegram with the following explanation: "Am happy

and honored by your acquisition. According to Nostradamus, the

apparition of monsters is a presage of war. This canvas was painted

in the mountains of Semmering a few months before the Anschluss and it

has a prophetic character. The women-horses represent the maternal

river-monsters, the flaming giraffe the male cosmic apocalyptic

monster. The angel-cat is the divine heterosexual monster, the

hour-glass the metaphysical monster. Gala and Dali together the

sentimental monster. The little lonely blue dog is not a true

monster." The theme of the women-horses that one sees here in a herd

bathing in a pond is the same as in Invisible Sleeping Woman,

Horse, Lion. Here the shapes have changed completely: three years

later they will give birth to a series of pictures entitled The

Marsupial Centaurs. About the double figure seen in the

foreground, holding a butterfly and an hourglass in his hands, the

painter has stated precisely that it was the Pre-Raphaelite result of

the double portrait of Dali and Gala painted right behind it.

Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937)

Get