Art by Caravaggio

Caravaggio was an Italian painter whose revolutionary technique of

tenebrism, or dramatic, selective illumination of form out of deep

shadow, became a hallmark of Baroque painting. Caravaggio was the best

exemplar of naturalistic painting in the early 17th century.

Caravaggio was a "wild" and violent painter - screams of terror and

images of horror assume a prominent place in many of Caravaggio's

works.

Caravaggio was an Italian painter whose revolutionary technique of

tenebrism, or dramatic, selective illumination of form out of deep

shadow, became a hallmark of Baroque painting. Caravaggio was the best

exemplar of naturalistic painting in the early 17th century.

Caravaggio was a "wild" and violent painter - screams of terror and

images of horror assume a prominent place in many of Caravaggio's

works.

- Supper at Emmaus (1602)

- The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1602)

- The Inspiration of Saint Matthew (1602)

- The Sacrifice of Isaac (Detail) (1602)

- The Sacrifice of Isaac (1602)

- Amor Victorious (1603)

- The Crowning with Thorns (1603)

- The Entombment (Detail) (1603)

- The Entombment (1603)

- St. John the Baptist (1604)

- Madonna di Loreto (1605)

- The Crowning with Thorns (1605)

- The Sacrifice of Isaac (1605)

- Ecce Homo (1606)

- Madonna with the Serpent (1606)

- St. Francis (1606)

- St. Jerome 2 (1606)

- St. Jerome (1606)

- Supper at Emmaus (1606)

- The Death of the Virgin (Detail) (1606)

- The Death of the Virgin (1606)

- Christ at the Column (1607)

- Flagellation (1607)

- Madonna del Rosario (1607)

- Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607)

- St. Jerome (1607)

- The Crucifixion of St. Andrew (1607)

- The Seven Acts of Mercy (1607)

- Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608)

- Burial of St. Lucy (1608)

- Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt (1608)

- Sleeping Cupid (1608)

- St. John the Baptist at the Well (1608)

- Adoration of the Shepherds (1609)

- David (1609)

- Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence (1609)

- Salome with the Head of the Baptist (1609)

- The Annunciation (1609)

- The Raising of Lazarus (1609)

- The Tooth-Drawer (1609)

- St. John the Baptist (1610)

Supper at Emmaus (1602)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Supper at Emmaus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The gospel according to St Luke (24:13-32) tells of the meeting of two disciples with the resurrected Christ. It is only during the meal that his companions recognize him in the way he blesses and breaks the bread. But with that, the vision of Christ vanishes. In the gospel according to St Mark (16:12) he is said to have appeared to them "in an other form" which is why Caravaggio did not paint him with a beard at the age of his crucifixion, but as a youth.

a high-quality picture of

Supper at Emmaus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The gospel according to St Luke (24:13-32) tells of the meeting of two disciples with the resurrected Christ. It is only during the meal that his companions recognize him in the way he blesses and breaks the bread. But with that, the vision of Christ vanishes. In the gospel according to St Mark (16:12) he is said to have appeared to them "in an other form" which is why Caravaggio did not paint him with a beard at the age of his crucifixion, but as a youth.

The host seems interested but somewhat confused at the surprise and emotion shown by the disciples. The light falling sharply from the top left to illuminate the scene has all the suddenness of the moment of recognition. It captures the climax of the story, the moment at which seeing becomes recognizing. In other words, the lighting in the painting is not merely illumination, but also an allegory. It models the objects, makes them visible to the eye and is at the same time a spiritual portrayal of the revelation, the vision, that will be gone in an instant.

Caravaggio has offset the transience of this fleeting moment in the tranquillity of his still life on the table. On the surfaces of the glasses, crockery, bread and fruit, poultry and vine leaves, he unfurls all the sensual magic of textural portrayal in a manner hitherto unprecedented in Italian painting.

The realism with which Caravaggio treated even religious subjects - apostles who look like labourers, the plump and slightly feminine figure of Christ - met with the vehement disapproval of the clergy.

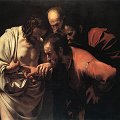

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1602)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture seems to belong to the same group as the second St Matthew and the Angel and The Sacrifice of Isaac because the same model reappears as the apostle at the apex of this composition. Like the first St Matthew and the Angel this picture belonged to Vincenzo Giustiniani and then entered the Prussian royal collection. Fortunately it was kept in Potsdam and so it survived the last war intact. This is the most copied painting of Caravaggio, 22 copies from the 17th century are known.

a high-quality picture of

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture seems to belong to the same group as the second St Matthew and the Angel and The Sacrifice of Isaac because the same model reappears as the apostle at the apex of this composition. Like the first St Matthew and the Angel this picture belonged to Vincenzo Giustiniani and then entered the Prussian royal collection. Fortunately it was kept in Potsdam and so it survived the last war intact. This is the most copied painting of Caravaggio, 22 copies from the 17th century are known.

According to St John's Gospel, Thomas missed one of Christ's appearances to the Apostles after His resurrection. He therefore announced that, unless he could thrust his hand into Christ's side, he would not believe what he had been told. A week later Christ appeared, asked Thomas to reach out his hands to touch Him and said, 'Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.'

This drama of disbelief seems to have touched Caravaggio personally. Few of his paintings are physically so shocking - his Thomas pushes curiosity to its limits before he will say, 'My Lord and my God.' The classical composition carefully unites the four heads in the quest for truth. Christ's head is largely in shadow, as He is the person who is the least knowable. He also has a beauty that had not been evident in the Mattei paintings of His arrest and appearance at Emmaus.

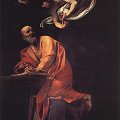

The Inspiration of Saint Matthew (1602)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Inspiration of Saint Matthew for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1565 the French Monsignor Matteo Contarelli acquired a chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, but when he died twenty years later it had not yet been decorated. The executor of his will, Virgilio Crescenzi, and later his son, Giacomo, undertook the task. The decorative scheme called for a statue of St Matthew and the Angel, commissioned first to Gerolamo Muziano, and then to the Flemish sculptor Cobaert, for the high altar; and for a fresco cycle for the walls and ceiling by Cavalier d'Arpino. The latter decorated the vault in 1591-93, but the walls were left bare (this may reflect at least in part the Crescenzis' intentions to speculate on the interest on the Contarelli estate). On 13 June 1599 a contract was stipulated before a notary by which Caravaggio undertook to execute two paintings for the lateral walls, for which he was paid the following year (1600), after the paintings had been set in place. Later, on 7 February 1602, after Cobaert's statue had been judged unsatisfactory, an altarpiece was entrusted to Caravaggio in a separate contract that called for delivery of the work by 32 May, the Feast of the Pentecost. This painting was rejected, the artist made another one (which was accepted) in a surprisingly brief time, receiving payment for this second work on 22 September.

a high-quality picture of

The Inspiration of Saint Matthew for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1565 the French Monsignor Matteo Contarelli acquired a chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, but when he died twenty years later it had not yet been decorated. The executor of his will, Virgilio Crescenzi, and later his son, Giacomo, undertook the task. The decorative scheme called for a statue of St Matthew and the Angel, commissioned first to Gerolamo Muziano, and then to the Flemish sculptor Cobaert, for the high altar; and for a fresco cycle for the walls and ceiling by Cavalier d'Arpino. The latter decorated the vault in 1591-93, but the walls were left bare (this may reflect at least in part the Crescenzis' intentions to speculate on the interest on the Contarelli estate). On 13 June 1599 a contract was stipulated before a notary by which Caravaggio undertook to execute two paintings for the lateral walls, for which he was paid the following year (1600), after the paintings had been set in place. Later, on 7 February 1602, after Cobaert's statue had been judged unsatisfactory, an altarpiece was entrusted to Caravaggio in a separate contract that called for delivery of the work by 32 May, the Feast of the Pentecost. This painting was rejected, the artist made another one (which was accepted) in a surprisingly brief time, receiving payment for this second work on 22 September.

The first version of the St Matthew and the Angel was purchased by Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani and then ended up in Berlin, where it was destroyed in the Second World War. The second version (this picture) still stands over the altar today.

The first version was a masterpiece of the artist. It contained, in the angel who with gentle indulgence guided the saint's uncertain hand as he wrote, one of the most charming figures ever painted by the artist. The first painting was criticised for Matthew's lack of decorum. In the final version, likewise a splendid feat of imagination but certainly less fascinating than the first, the angel much more correctly counts on his fingers, in the traditional scholastic fashion, the arguments than the saint should take note of and develop. A whirlwind of drapery envelops the angel. The saint balances on his bench, in precarious equilibrium, like a modern schoolboy; but this time the unorthodox elements do not seem to have raised particular objections.

The Sacrifice of Isaac (Detail) (1602)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Sacrifice of Isaac (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The angel, seen in profile at the left-hand edge of the picture, is pointing to a view of the landscape with his powerfully extended index-finger. At first glance he is indicating the ram rather then Isaac, but his finger is pointing beyond this towards the liberating landscape on the right.

a high-quality picture of

The Sacrifice of Isaac (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The angel, seen in profile at the left-hand edge of the picture, is pointing to a view of the landscape with his powerfully extended index-finger. At first glance he is indicating the ram rather then Isaac, but his finger is pointing beyond this towards the liberating landscape on the right.

The Sacrifice of Isaac (1602)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Sacrifice of Isaac for your computer or notebook. ‣

Caravaggio painted a version of this subject for Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII and this could be the picture.

a high-quality picture of

The Sacrifice of Isaac for your computer or notebook. ‣

Caravaggio painted a version of this subject for Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII and this could be the picture.

The artist thrusts the action to the front of the picture frame like a sculpted frieze. Old Abraham, with features reminiscent of the second St Matthew, is intercepted in the act of slitting his son's throat by an admonishing angel who with his right hand prevents the murder and with his left points to the substitute victim. Light directs the viewer to scan the scene from left to right as it picks out the angel's shoulder and left hand, the quizzical face of Abraham, the right shoulder and terrified face of Isaac and finally the docile ram. A continuous movement links the back of the angel's neck to Isaac's profile; and angel and boy have a family likeness.

Caravaggio combines a hint of horror with pastoral beauty. In the foreground the sharp knife is silhouetted against the light on Isaac's arm. In the distance is one of Caravaggio's rare landscapes, a glimpse perhaps of the Alban hills round Rome and an acknowledgement of the skill of his one serious rival, Annibale Carracci, whose landscapes were particularly admired.

Amor Victorious (1603)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Amor Victorious for your computer or notebook. ‣

This paintings was always considered one of Caravaggio's great masterpieces. He painted it for Marchese Giustiniani. The figure sets up a direct, special and privileged relationship with the viewer, with an immediate appeal that is truly extraordinary. One is bewildered by this painting, by the absolute freedom that the subject obviously enjoys, detaching himself from mere mortals who must obey the laws of nature. The figure is in the act of mocking the world with a complete impunity, a self-assurance that produce a mixture of astonishment and envy. The figure has a torso that recalls Michelangelo's Victory.

a high-quality picture of

Amor Victorious for your computer or notebook. ‣

This paintings was always considered one of Caravaggio's great masterpieces. He painted it for Marchese Giustiniani. The figure sets up a direct, special and privileged relationship with the viewer, with an immediate appeal that is truly extraordinary. One is bewildered by this painting, by the absolute freedom that the subject obviously enjoys, detaching himself from mere mortals who must obey the laws of nature. The figure is in the act of mocking the world with a complete impunity, a self-assurance that produce a mixture of astonishment and envy. The figure has a torso that recalls Michelangelo's Victory.

The painting probably shows Earthly Love triumphant over the Virtues and Sciences, symbolized by the musical instruments, pen and book, compass and square, scepter, laurel, and armor at his feet.

Caravaggio's Amor, a teenager with a gloating smile, "reigns" over a pile of weapons, instruments, a book (sheet music), drawing utensils, and a laurel wreath. He places his left knee lightly over these objects, while he holds a bunch of arrows in his right hand. Since the attributes of war, military glory, science and arts are scattered at Amor's feet, the painting reminds the viewer of a Vanitas still-life. Some objects in this still-life are emphasized: pieces of a suit of armour, a lute and a violin with a bow. These may refer to Mars and Venus, who, according to some classical genealogies, including that of Virgil's Aeneid I. 664, were the parents of the playful little winged deity Amor.

Thus in this painting the musical instruments represent Venus herself rather than either art in general or, through the association of fading melodies, transitoriness of human life. It is likely, of course, that the viewer of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries may have thought of all the previous connotations, too, since he was used to the multiple meanings of symbols.

The Crowning with Thorns (1603)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Crowning with Thorns for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture creates a different kind of drama than the Crowning with Thorns in Vienna, which is also disputed. The vertical format allows us to concentrate on Christ, who occupies the center of the picture. The figure of a man, naked from the waist up, sitting on a chair in front of a barrier in the foreground, holding the rope with which Christ's hands are bound, leads the eye towards him. A second man in a brilliant red robe is almost gently gripping the victim by his upper body and upper left arm. A third assistant is pressing the crown down so hard on to Christ's head with his stick that a drop of blood is running down his temple.

a high-quality picture of

The Crowning with Thorns for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture creates a different kind of drama than the Crowning with Thorns in Vienna, which is also disputed. The vertical format allows us to concentrate on Christ, who occupies the center of the picture. The figure of a man, naked from the waist up, sitting on a chair in front of a barrier in the foreground, holding the rope with which Christ's hands are bound, leads the eye towards him. A second man in a brilliant red robe is almost gently gripping the victim by his upper body and upper left arm. A third assistant is pressing the crown down so hard on to Christ's head with his stick that a drop of blood is running down his temple.

The Entombment (Detail) (1603)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Entombment (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The stone slab makes its appearance in the picture with terrifying power. According to one's attitude, one will detect in this paiting either irreverence or profound religious bewilderment in the face of the death of Christ, because it presents the meaning of the sacred event - the unique occasion - which lies in the heart of Church ritual, in a tangible visual form.

a high-quality picture of

The Entombment (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The stone slab makes its appearance in the picture with terrifying power. According to one's attitude, one will detect in this paiting either irreverence or profound religious bewilderment in the face of the death of Christ, because it presents the meaning of the sacred event - the unique occasion - which lies in the heart of Church ritual, in a tangible visual form.

The Entombment (1603)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Entombment for your computer or notebook. ‣

Of all Caravaggio's paintings, The Entombment is probably the most monumental. A strictly symmetrical group is built up from the slab of stone that juts diagonally out of the background.

a high-quality picture of

The Entombment for your computer or notebook. ‣

Of all Caravaggio's paintings, The Entombment is probably the most monumental. A strictly symmetrical group is built up from the slab of stone that juts diagonally out of the background.

The painting is from the altar of the Chiesa Nuova in Rome, which is dedicated to the Pieta. The embalming of the corpse and the entombment are actually secondary to the the Mourning of Mary which is the focal point of the lamentation.

Nothing distinguished Caravaggio's history paintings more strongly from the art of the Renaissance than his refusal to portray the human individual as sublime, beautiful and heroic. His figures are bowed, bent, cowering, reclining or stooped. The self confident and the statuesque have been replaced by humility and subjection.

St. John the Baptist (1604)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

In around 1605 Caravaggio dealt with St. John the Baptist in two splendid compositions, one in the Kansas City Gallery, the other in the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Antica in Rome. The former is laid out vertically, the latter horizontally. Both lend themselves to a modernistic reading aimed at pointing out a certain air between contempt and arrogance. In effect what we are dealing with here are splendid exercises in modeling the body through the play of light and shadow.

a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

In around 1605 Caravaggio dealt with St. John the Baptist in two splendid compositions, one in the Kansas City Gallery, the other in the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Antica in Rome. The former is laid out vertically, the latter horizontally. Both lend themselves to a modernistic reading aimed at pointing out a certain air between contempt and arrogance. In effect what we are dealing with here are splendid exercises in modeling the body through the play of light and shadow.

In the version now in Kansas City, the figure is set before a dense curtain of plants; in that in Rome, there is only the trunk of a cypress tree, on the left. Both are admirable feats of painting, and it is understandable that collectors competed with each other for the artist's works. Caravaggio in turn knew how to make apparently uninteresting religious themes into paintings desirable even for his aristocratic patrons.

Madonna di Loreto (1605)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna di Loreto for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1603 money was given by the heirs of one Ermete Cavalletti for the decoration of the family chapel in the church of San Agostino, not far from the Piazza Navona, at the centre of Caravaggio's Rome. By the end of 1604 this painting was installed in a spot where it has been ever since. In the winter of 1603-4 Caravaggio had been in Tolentino, not far from the shrine of Loreto, and he may have gone there to see the supposed Holy House of Nazareth.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna di Loreto for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1603 money was given by the heirs of one Ermete Cavalletti for the decoration of the family chapel in the church of San Agostino, not far from the Piazza Navona, at the centre of Caravaggio's Rome. By the end of 1604 this painting was installed in a spot where it has been ever since. In the winter of 1603-4 Caravaggio had been in Tolentino, not far from the shrine of Loreto, and he may have gone there to see the supposed Holy House of Nazareth.

He has made simple devotion affecting. Two pilgrims - pellegrini in Italian - kneel in prayer before the statue beside a pillar, while the Madonna and Child, living to the eyes of faith, look down on them in quiet attention. (The painting is also called Madonna dei Pellegrini.) The woman has a ruckled bonnet and the dirty soles of the man's feet are so close to the spectator that they cannot be avoided. The haloes on the sacred figures and their raised position remove them from our world, but their beauty contains no hint of arrogance - they gaze at the world with gentle sympathy.

Some have seen in this Madonna the latest woman in Caravaggio's life Lena or Maddalena, over whom he had a fight. She is painted with love, but has only one rich passage in the left arm of her dress; elsewhere colour is toned down. Her craning neck was to be almost a mannerism in Caravaggio's works of this period, but here the pose is convincing.

The Crowning with Thorns (1605)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Crowning with Thorns for your computer or notebook. ‣

A much debated painting. Some scholars give the painting to Caracciolo, others consider it as a high quality copy of a lost Caravaggio.

a high-quality picture of

The Crowning with Thorns for your computer or notebook. ‣

A much debated painting. Some scholars give the painting to Caracciolo, others consider it as a high quality copy of a lost Caravaggio.

The front boundary of the picture is articulated by a wooden barrier, on which the captain is leaning, in order to observe the action but take no part in it. He watches the executioner's half-naked assistants abuse Christ at his behest. The powerful figure of the suffering victim, sitting almost naked on a bench, seems larger than he is. Christ's shoulderline continues the shallow diagonal which began with the white feather of the captain's hat, on the left.

The Sacrifice of Isaac (1605)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Sacrifice of Isaac for your computer or notebook. ‣

The landscape has faded out. Against a dark background, the story is pieced together out of figures. As if he had clambered up the mountain behind father and son, the angel brings them the ram, and speaks to Abraham, who is already relaxing his grip on Isaac's hair. Whether this colorful picture, with its rich lighting, was really painted by Caravaggio, is open to doubt.

a high-quality picture of

The Sacrifice of Isaac for your computer or notebook. ‣

The landscape has faded out. Against a dark background, the story is pieced together out of figures. As if he had clambered up the mountain behind father and son, the angel brings them the ram, and speaks to Abraham, who is already relaxing his grip on Isaac's hair. Whether this colorful picture, with its rich lighting, was really painted by Caravaggio, is open to doubt.

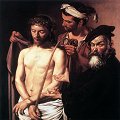

Ecce Homo (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Ecce Homo for your computer or notebook. ‣

The attribution to Caravaggio is debated, however, most of the scholars accept it as an original Caravaggio in a bad state of preservation. The figure of Pilate is an assumed self-portrait of Caravaggio.

a high-quality picture of

Ecce Homo for your computer or notebook. ‣

The attribution to Caravaggio is debated, however, most of the scholars accept it as an original Caravaggio in a bad state of preservation. The figure of Pilate is an assumed self-portrait of Caravaggio.

There is another version in the Museo Nazionale in Messina which is probably the work of a Sicilian follower of Caravaggio or a crude copy of an original Caravaggio.

Madonna with the Serpent (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna with the Serpent for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting is also called Madonna dei Palafrenieri).

a high-quality picture of

Madonna with the Serpent for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting is also called Madonna dei Palafrenieri).

It was in late 1605 that Caravaggio finally obtained a commission for St Peter's. The papal grooms or palafrenieri invited him to paint an altarpiece for them, and in April 1606 it was exhibited in the basilica for a few days before being moved to the grooms' church of Sant'Anna nearby. If the sympathy of Paul V had facilitated the commission, his nephew soon profited by it, for later in the year, just after the painter had left Rome for good, it was added to the Borghese collection.

Under the watchful gaze of St Anne, Jesus's apocryphal grandmother, Mary helps a naked Christ Child to tread on a snake. The snake may be interpreted as Satan and indirectly as heresy, for Mary and Jesus are free of sin and its consequences, Mary as a virgin mother and by reason of her Immaculate Conception, Jesus as God made man - and they combine to crush the serpent under their feet.

This large iconographic canvas has a certain humanity thanks to Mary's naturalness and the lack of inhibition with which Caravaggio depicts Christ naked (a fact that gave offence to some connoisseurs at the time, according to Bellori). Though their haloes are aligned, a dark gulf separates the pretty Mary from her ugly mother; and if the palafrenieri were willing to let Cardinal Scipione Borghese buy the picture so soon after they had received it and paid for it, it may have been because they disliked the unflattering depiction of their patroness.

St. Francis (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Francis for your computer or notebook. ‣

The founder of the Franciscan Order was the first person to experience the miracle of stigmatization of his own body. In other words, he was marked out by Christ's wounds. Here he is reduced to the ideal state of penance in the wilderness - a state equally valid for saints and pious people. Caravaggio shows no sign of reinterpreting the story unconventionally. His rather traditional approach may derive from the fact that the composition is probably a commission from the papal family. They owned the township known as Carpineto, from where an almost identical second version, stored at present in the Palazzo Venezia, Rome, originated. Stylistically, the painting is very closely related to the Brera Supper in Emmaus, which was probably painted in Latium.

a high-quality picture of

St. Francis for your computer or notebook. ‣

The founder of the Franciscan Order was the first person to experience the miracle of stigmatization of his own body. In other words, he was marked out by Christ's wounds. Here he is reduced to the ideal state of penance in the wilderness - a state equally valid for saints and pious people. Caravaggio shows no sign of reinterpreting the story unconventionally. His rather traditional approach may derive from the fact that the composition is probably a commission from the papal family. They owned the township known as Carpineto, from where an almost identical second version, stored at present in the Palazzo Venezia, Rome, originated. Stylistically, the painting is very closely related to the Brera Supper in Emmaus, which was probably painted in Latium.

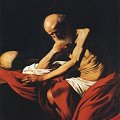

St. Jerome 2 (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome 2 for your computer or notebook. ‣

Just as Protestants wished to translate the Bible into local languages to make the Word of God accessible to ordinary believers, so Catholics were keen to justify the use of the standard Latin version, made by St Jerome in the late fourth century. Jerome had been baptized by one pope, had been given his task as translator by another and had called St Peter the first bishop of Rome. Among the Latin Fathers of the Church he was a powerful ally against modern heretics, who attacked the cult of the saints, restricted the use of Latin to the learned and viewed the papacy as the whore of Babylon. It was wholly appropriate that this image was bought by Scipione Borghese soon after he was made a cardinal in 1605 by his uncle, the new Pope Paul V.

a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome 2 for your computer or notebook. ‣

Just as Protestants wished to translate the Bible into local languages to make the Word of God accessible to ordinary believers, so Catholics were keen to justify the use of the standard Latin version, made by St Jerome in the late fourth century. Jerome had been baptized by one pope, had been given his task as translator by another and had called St Peter the first bishop of Rome. Among the Latin Fathers of the Church he was a powerful ally against modern heretics, who attacked the cult of the saints, restricted the use of Latin to the learned and viewed the papacy as the whore of Babylon. It was wholly appropriate that this image was bought by Scipione Borghese soon after he was made a cardinal in 1605 by his uncle, the new Pope Paul V.

In pre-Reformation days Jerome was shown with a pet lion and a cardinal's hat. Now Catholic reformers wished to pare religious art down to its essentials, and the good-living cardinal, whose ample features were to be sculpted and caricatured by Bernini, acquired a painting that was as austere as it was sombre. The thin old man, whose face is reminiscent of the model who had been Abraham, Matthew and one of the Apostles with Thomas, sits reflecting on a codex of the Bible while his right hand is poised to write. Whereas in the Renaissance, Antonello da Messina and Durer had made him into a wealthy scholar, Caravaggio reduces Jerome's possessions to a minimum. The text he holds open, a second closed one and a third kept open by a skull are perched on a small table. Harsh lighting emphasizes the sinewy muscles of his tired arms and the parallel between his bony head and the skull - man is born to die, but the Word of God lives forever.

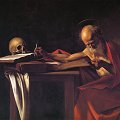

St. Jerome (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome for your computer or notebook. ‣

The suntan revealed in this upright picture on the old man's face and hands, in contrast to the light color on his arms and upper body, indicates that Caravaggio was again studying from a living model. Strong shadows disturb the structural features of the upper body. With only a piece of white drapery around his loins, and his Cardinal-red mantle slung across his legs, the old man has his left hand resting on his mantle, which also covers the table, whilst he is pensively stroking his beard with his right hand. Although his head is lowered, he is not looking at the skull in front of him. That said, the skull's empty eye-sockets appear to be staring at him.

a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome for your computer or notebook. ‣

The suntan revealed in this upright picture on the old man's face and hands, in contrast to the light color on his arms and upper body, indicates that Caravaggio was again studying from a living model. Strong shadows disturb the structural features of the upper body. With only a piece of white drapery around his loins, and his Cardinal-red mantle slung across his legs, the old man has his left hand resting on his mantle, which also covers the table, whilst he is pensively stroking his beard with his right hand. Although his head is lowered, he is not looking at the skull in front of him. That said, the skull's empty eye-sockets appear to be staring at him.

Supper at Emmaus (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Supper at Emmaus for your computer or notebook. ‣

This later version of the subject is more restrained in colour and action than that in the National Gallery, London, less symbolic, more reverential. Instead of sumptuous still-life, we see only bread, a bowl, a tin plate, and a jug. The gestures of surprise are much the same though differently distributed.

a high-quality picture of

Supper at Emmaus for your computer or notebook. ‣

This later version of the subject is more restrained in colour and action than that in the National Gallery, London, less symbolic, more reverential. Instead of sumptuous still-life, we see only bread, a bowl, a tin plate, and a jug. The gestures of surprise are much the same though differently distributed.

An elderly innkeeper and an elderly maid wait anxiously on the three men who have arrived in the small village. The disciple to the left turns his face away towards Christ, the one on the right is seen in three-quarter profile. This time, instead of recoiling ftom Christ, they len forward in his direction, as with a tranquil gesture he blesses the bread.

The Death of the Virgin (Detail) (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Death of the Virgin (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Mary lies as though suspended on the coffin. In the foreground Mary Magdalene is lamenting, drained of emotion and without any hope of redemption.

a high-quality picture of

The Death of the Virgin (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Mary lies as though suspended on the coffin. In the foreground Mary Magdalene is lamenting, drained of emotion and without any hope of redemption.

It was pointed out that the artist has not made a representation of death, but has shown a real death. Thus the painting offends the sensibility not only of its own time, but of all times, because of what it suggest about the obscure, fearful meaning of the end of life.

The Death of the Virgin (1606)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Death of the Virgin for your computer or notebook. ‣

This, the largest picture that Caravaggio had yet produced, did not end up in the place for which it was made. In 1602 a papal legal adviser, Laerzio Cherubini, commissioned a Death of the Virgin for the Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala in Trastevere; it was to be finished by 1603. When they saw it, the friars found it alarming, because the Madonna was modelled on a prostitute with whom Caravaggio was in love (according to Mancini), because her legs were exposed (Baglione), because her swollen body was too realistic (Bellori) - for whichever reason, they felt prompted to reject it. After Caravaggio had left Rome, Rubens urged his master, the Duke of Mantua, to buy it. Along with the rest of the movable Gonzaga collection it was bought by Charles I of England and, after he had been executed, was sold to Louis XIV. What the friars could not endure was favoured at court.

a high-quality picture of

The Death of the Virgin for your computer or notebook. ‣

This, the largest picture that Caravaggio had yet produced, did not end up in the place for which it was made. In 1602 a papal legal adviser, Laerzio Cherubini, commissioned a Death of the Virgin for the Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala in Trastevere; it was to be finished by 1603. When they saw it, the friars found it alarming, because the Madonna was modelled on a prostitute with whom Caravaggio was in love (according to Mancini), because her legs were exposed (Baglione), because her swollen body was too realistic (Bellori) - for whichever reason, they felt prompted to reject it. After Caravaggio had left Rome, Rubens urged his master, the Duke of Mantua, to buy it. Along with the rest of the movable Gonzaga collection it was bought by Charles I of England and, after he had been executed, was sold to Louis XIV. What the friars could not endure was favoured at court.

The painting is severe, sad and still. Under a red canopy hanging from a barely visible ceiling, the disciples are grouped round the corpse (fixed on a bed in rigor mortis), most standing to the left. Light coming from a window high on the left picks out their foreheads and bald pates, before falling on the upper part of the Virgin's body. Above her stands the young, mourning St John the Evangelist who had been given special charge of her; in front, the seated Mary Magdalene stoops forward and almost buries her head in her lap.

In the predominant colours - red, orange, dark green - Caravaggio uses a slightly wider range than in his later, darker Roman paintings, but nowhere else did he achieve a mood of such overwhelming solemnity. Mary's companions, her Son's followers, are struck dumb by their grief, like relief sculptures on antique tombs. There is no suggestion that their sorrow will be turned into joy or that Mary will be assumed into heaven.

Christ at the Column (1607)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Christ at the Column for your computer or notebook. ‣

The movement of these figures. who are sharply divided into two different halves of the picture, is conceived entirely in terms of the light coming from the left. In the process, the flagellation column, usually a decisive motif, appears as little more than a symbol of Christ, without having any effect on the pictorial space, which is immersed in the blackness of the background. Judging by the assistants rather than by Christ, this picture dates from the time of Caravaggio's first stay in Naples.

a high-quality picture of

Christ at the Column for your computer or notebook. ‣

The movement of these figures. who are sharply divided into two different halves of the picture, is conceived entirely in terms of the light coming from the left. In the process, the flagellation column, usually a decisive motif, appears as little more than a symbol of Christ, without having any effect on the pictorial space, which is immersed in the blackness of the background. Judging by the assistants rather than by Christ, this picture dates from the time of Caravaggio's first stay in Naples.

Flagellation (1607)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Flagellation for your computer or notebook. ‣

This major painting, which (like the Seven Works of Mercy) dates from Caravaggio's first visit to Naples, is disquieting in its own special way. In May 1607 he was paid by Tommaso de' Franchis for an altarpiece to hang in the family chapel in San Domenico, where it stayed till 1972.

a high-quality picture of

Flagellation for your computer or notebook. ‣

This major painting, which (like the Seven Works of Mercy) dates from Caravaggio's first visit to Naples, is disquieting in its own special way. In May 1607 he was paid by Tommaso de' Franchis for an altarpiece to hang in the family chapel in San Domenico, where it stayed till 1972.

The atmosphere is so dense that the pillar before which Christ is being whipped can hardly be made out, but the handling of paint is so fluent that the cruel action taking place has its own powerful rhythm. The viewer is caught up in the horror.

The near-naked Christ is being twisted into position by the torturer on the right while the torturer on the left tears at his hair. At the bottom left a third tormentor stoops to prepare his scourge.

The composition is derived from a fresco by Sebastiano del Piombo, but its restricted palette of dismal colours gives it a grim force that few earlier paintings had equaled.

Madonna del Rosario (1607)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna del Rosario for your computer or notebook. ‣

In its huge scale and multi-figured design the grandest of Caravaggio's paintings, this may have been commissioned by the Duke of Modena in 1605 and undertaken in Naples. It was offered to the Duke of Mantua in 1607 and was bought by a consortium of Flemish artists, including Rubens, by whom it was offered to the Dominican church in Antwerp.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna del Rosario for your computer or notebook. ‣

In its huge scale and multi-figured design the grandest of Caravaggio's paintings, this may have been commissioned by the Duke of Modena in 1605 and undertaken in Naples. It was offered to the Duke of Mantua in 1607 and was bought by a consortium of Flemish artists, including Rubens, by whom it was offered to the Dominican church in Antwerp.

The theme is Dominican. St Dominic and his friars spread the devotion of the rosary; and here the Madonna, as Queen of Heaven, issues orders to the saint to her right, who clutches a rosary, and the Dominican St Peter Martyr to her left. Beside St Peter Martyr stands the most famous of Dominican theologians, St Thomas Aquinas.

Madonna, Child and saints form a heavenly triangle concealed from the classically costumed suppliants at the front, who kneel in prayer with arms outstretched to St Dominic, while a donor in modern ruff and doublet eyes the viewer. The column to the left and the curtain overhead add to the formality of the scene. Caravaggio achieves an elaborate ordering and interlocking of forms that heralds the typical Baroque altarpiece.

Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

On his way back to Rome Caravaggio returned to Naples. This harsh late work has none of the beauty of some of the late Sicilian pictures, such as the altarpiece stolen from the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo, and it may reflect the assault Caravaggio endured in the Osteria del Cerriglio in the city. A sense of the tired mood of one aware of the pointlessness of a ruthless vendetta pervades the painting.

a high-quality picture of

Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

On his way back to Rome Caravaggio returned to Naples. This harsh late work has none of the beauty of some of the late Sicilian pictures, such as the altarpiece stolen from the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo, and it may reflect the assault Caravaggio endured in the Osteria del Cerriglio in the city. A sense of the tired mood of one aware of the pointlessness of a ruthless vendetta pervades the painting.

The Baptist has been executed for denouncing Salome's mother Herodias over her illicit marriage with Herod. Caravaggio uses the device of planting two heads - Salome's and her maid's (or her mother's) - so close together that they seem to grow out of one body as the contrasting stages of youth and age. This had been a trait of Leonardo's, and the way that the head of St John is presented to the spectator recalls a picture by Leonardo's pupil Luini, whose Salome also looks away from her victim. The executioner takes no joy in what he has been commanded to do. He feels only a stunned emotion in keeping with the sombre tones that Caravaggio adopts.

St. Jerome (1607)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture of the holy scholar was made for Ippolito Malaspina, a Maltese knight whose coat of arms is on the wooden panel to the right. He was connected by marriage to Caravaggio's patron Ottavio Costa and was a confidant of the Grand Master, who may have been used as the model for the saint (similarly Van Dyck was to use the sister of the Queen of England as model for the Madonna). The saint does indeed look like the knight in a recently discovered portrait by Caravaggio, who has been identified by some as Wignacourt himself.

a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture of the holy scholar was made for Ippolito Malaspina, a Maltese knight whose coat of arms is on the wooden panel to the right. He was connected by marriage to Caravaggio's patron Ottavio Costa and was a confidant of the Grand Master, who may have been used as the model for the saint (similarly Van Dyck was to use the sister of the Queen of England as model for the Madonna). The saint does indeed look like the knight in a recently discovered portrait by Caravaggio, who has been identified by some as Wignacourt himself.

The composition is planned in terms of triangles. One rises from the table to the saint's head, another has its apex at the cardinal's hat on the wall to the left, a third recedes to the bedstead at the back on the right. This simple design helps convey an idea of simplicity. St Jerome has no halo, his workbench is rudimentary, he does not own any folios, he has one candle to see by, a crucifix to meditate on, a stone to beat against his chest, and a skull to remind him of his mortality. He is partly naked because he lives an eremitical life in the desert of Judaea. A steady light shines on his torso and picks out the red cloak round his legs. The source of the light is outside the picture, and can be interpreted as Christ, Light of the World.

The Crucifixion of St. Andrew (1607)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Crucifixion of St. Andrew for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Andrew was patron saint of Constantinople. From that city his body had been snatched by crusaders and brought to Amalfi, just one bay south of Naples. The Count of Benevente, viceroy to Philip III, King of Spain, was charged by his royal master to renovate the crypt in the cathedral of Amalfi, where the saint is buried; and it must have been while he was so engaged that he asked Caravaggio to paint him the scene of the saint's death. The painting was in the viceroy's grandson's inventory in 1653, then disappeared for over two centuries till it was bought from a private Spanish collection.

a high-quality picture of

The Crucifixion of St. Andrew for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Andrew was patron saint of Constantinople. From that city his body had been snatched by crusaders and brought to Amalfi, just one bay south of Naples. The Count of Benevente, viceroy to Philip III, King of Spain, was charged by his royal master to renovate the crypt in the cathedral of Amalfi, where the saint is buried; and it must have been while he was so engaged that he asked Caravaggio to paint him the scene of the saint's death. The painting was in the viceroy's grandson's inventory in 1653, then disappeared for over two centuries till it was bought from a private Spanish collection.

It was customary to show Andrew crucified on a cross formed by two diagonals. According to the The Golden Legend, Aegeas, the proconsul of Patras, had Andrew held on the cross by ropes rather than nails, to prolong his suffering. But Andrew took advantage of his slow death to preach from the cross for two days, till the people threatened violence unless he were taken down. By this time Andrew had preached enough and, to die quickly, prayed that his limbs would be paralysed so that he could not be cut down. As a great light shines, he dies.

It is this moment that Caravaggio paints. The old man looks weary from his agony, and the sturdy executioner who tries to undo the thongs is twisted round in a vain attempt to release him. Below a small group are transfixed by Andrew's eloquence: an old woman with a goitre (Andrew cured throat infections), a knight in black shining armour (the sceptical Aegeas), a middle-aged man and, behind the knight, a young bravo. By restricting any sense of space Caravaggio has made a drama more intimate than the events of everyday life.

The Seven Acts of Mercy (1607)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Seven Acts of Mercy for your computer or notebook. ‣

From the fiefs of the Colonna family Caravaggio took refuge in Naples, in 1606. There he began to work again with his usual, astounding speed. Early in January 1607 he was paid for the immense altarpiece commissioned to him by the Pio Monte di Misericordia (where it may still be seen today). The painting shows the Seven Acts of Mercy. It is very complicated in its organization. Caravaggio actually had to add a series of figures (two angels and the Madonna and Child, the latter painted later) in the upper part of the painting, which make the composition of the picture the most complex, perhaps, in any of his works. Caravaggio did not paint exemplary episodes intended to stir the viewer to religious piety through the illustrative emphasis of gestures and feelings. Rather, he entrusted the educational effectiveness of his works to the evidence of things in themselves, in the conviction that nothing should be added above and beyond what is already contained in the intrinsic eloquence of the various poses.

a high-quality picture of

The Seven Acts of Mercy for your computer or notebook. ‣

From the fiefs of the Colonna family Caravaggio took refuge in Naples, in 1606. There he began to work again with his usual, astounding speed. Early in January 1607 he was paid for the immense altarpiece commissioned to him by the Pio Monte di Misericordia (where it may still be seen today). The painting shows the Seven Acts of Mercy. It is very complicated in its organization. Caravaggio actually had to add a series of figures (two angels and the Madonna and Child, the latter painted later) in the upper part of the painting, which make the composition of the picture the most complex, perhaps, in any of his works. Caravaggio did not paint exemplary episodes intended to stir the viewer to religious piety through the illustrative emphasis of gestures and feelings. Rather, he entrusted the educational effectiveness of his works to the evidence of things in themselves, in the conviction that nothing should be added above and beyond what is already contained in the intrinsic eloquence of the various poses.

The seven acts of mercy represented on the painting are the following. On the right appear the (1) burial of the dead and the episode of the so-called Carita Romana (Cimon's daughter giving her father suck in prison), which contains at once the two charitable acts of (2) visiting prisoners and (3) feeding the hungry. (4) Dressing the naked appears in the foreground, symbolized by St. Martin and the beggar. Next to this scene, the host and St. James of Compostela allude to the (5) offering of hospitality to pilgrims. (6) Relieving the thirsty is represented by Samson drinking from the ox jaw. The youth on the ground behind the beggar of St. Martin may also represent the merciful gesture of (7) caring for the sick.

We readily apprehend the artist's power of synthesis, which concentrates a conceptual content that is potentially quite dispersive, in the model behavior of a few figures. The large painting was widely copied and studied by seventeenth-century Neapolitan painters, who drew ideas and formal devices from it.

Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Beheading of Saint John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is the most important painting that Caravaggio made in Malta. It is still in the Oratorio di San Giovanni (now St John Museum) in La Valletta. This is one of Caravaggio's most extraordinary creations, for many it is his greatest masterpiece. It is characterized by a magical balance of all the parts. It is no accident that the artist brings back into the painting a precise reference to the setting, placing behind the figures, as a backdrop, the severe, sixteenth century architecture of the prison building, at the window of which, in a stroke of genius, two figures silently witness the scene (the commentators are thus drawn into the painting, and no longer projected, as in the Martyrdom of St Matthew, toward the outside).

a high-quality picture of

Beheading of Saint John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is the most important painting that Caravaggio made in Malta. It is still in the Oratorio di San Giovanni (now St John Museum) in La Valletta. This is one of Caravaggio's most extraordinary creations, for many it is his greatest masterpiece. It is characterized by a magical balance of all the parts. It is no accident that the artist brings back into the painting a precise reference to the setting, placing behind the figures, as a backdrop, the severe, sixteenth century architecture of the prison building, at the window of which, in a stroke of genius, two figures silently witness the scene (the commentators are thus drawn into the painting, and no longer projected, as in the Martyrdom of St Matthew, toward the outside).

This is a final compendium of Caravaggio's art. Well-known figures return (the old woman, the youth, the nude ruffian, the bearded nobleman), as do Lombard elements. The technical means adhere to the deliberate, programmatic limitation to which Caravaggio adapts them; but amid these soft tones, these dark colours, is an impressive sense of drawing that the artist does not give up, and that is visible even through the synoptic glints of light of his late works. This eminently classical balance, which projects the event beyond contingency, unleashes a harsh drama that is even more effective to the extent that, having given up the "aesthetic of exclamation" forever, Caravaggio limits every external, excessive sign of emotional emphasis. The painter signed in the Baptist's blood: "f (perhaps to understood as fecit rather than frater) michela...". This is the seal he placed on what may well be his greatest masterpiece.

Burial of St. Lucy (1608)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Burial of St. Lucy for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Lucy was a local saint of Syracuse, who had been denounced as a Christian by her former suitor and had died from her tortures in 304. Caravaggio may have worked in haste to produce a picture before the feast of St Lucy on 13 December. His Sicilian biographer states that he owed the commission to his friend Minniti, who may also have helped him paint it.

a high-quality picture of

Burial of St. Lucy for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Lucy was a local saint of Syracuse, who had been denounced as a Christian by her former suitor and had died from her tortures in 304. Caravaggio may have worked in haste to produce a picture before the feast of St Lucy on 13 December. His Sicilian biographer states that he owed the commission to his friend Minniti, who may also have helped him paint it.

Originally Lucy's head was severed from her body but later Caravaggio joined it and left just a slit in the front of her neck - perhaps recalling St Cecilia, whose still-intact body, with a gash in the nape of the neck, had been sculpted in 1600 by Maderno. A more local influence was the crypt of the Syracusan church where Lucy had been buried, for cavernous spaces dwarf the human actors.

The heavily-muscled grave-diggers emerge from murky shadows, the mourners are so much smaller that they seem placed some distance away, the officer directing operations beside the bishop is obscured and only the young man above the saint stands out poignantly in his red cloak. Characteristically, light imitates the action of the sun by falling from the right. The scene takes the viewer back to the age of the Church of the catacombs.

The painting was recently restored at the Istituto Centrale per il Restauro in Rome (all Caravaggio's Sicilian paintings have come down to us in a poor state of preservation) and transferred from the Basilica Santa Lucia to the Bellamo Museum in Syracuse.

Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt (1608)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt for your computer or notebook. ‣

As Grand Master of the Knights of St John of Malta, Alof de Wignacourt was head of a military order and a sovereign state, and he commissioned this portrait and maybe the second which was probably the model for St Jerome.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt for your computer or notebook. ‣

As Grand Master of the Knights of St John of Malta, Alof de Wignacourt was head of a military order and a sovereign state, and he commissioned this portrait and maybe the second which was probably the model for St Jerome.

The page in charge of Wignacourt's plumed helmet and cloak stands a little awkwardly within the composition, and his lively features would make him an attractive subject of his own right. Caravaggio may have been attempting to rival the portraiture of Titian.

Wignacourt is consciously dignified, relaxed and authoritative. His splendid black and gold Milanese armor glints in the light. Even if he was left-handed, the way he holds the baton, pointing upwards in his right hand and downwards in his left, is uncomfortable. As a reward for this painting Wignacourt gave the painter an honorary knighthood, but within three months the relationship had deteriorated and Caravaggio had fled in disgrace.

Sleeping Cupid (1608)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Sleeping Cupid for your computer or notebook. ‣

When Caravaggio received his honorary knighthood, his presence on Malta was likened to that of Apelles on the island of Cos. This curiously sombre little picture is the only classical relic of Caravaggio's time on Malta, to which an old inscription on the back of the canvas ascribes it. As the painting was in Florence by 1618, Caravaggio may have taken it with him when he fled.

a high-quality picture of

Sleeping Cupid for your computer or notebook. ‣

When Caravaggio received his honorary knighthood, his presence on Malta was likened to that of Apelles on the island of Cos. This curiously sombre little picture is the only classical relic of Caravaggio's time on Malta, to which an old inscription on the back of the canvas ascribes it. As the painting was in Florence by 1618, Caravaggio may have taken it with him when he fled.

The plump, solid figure is well articulated by the artist who had learnt in Rome all that he needed to know about human anatomy from antiquity and the Renaissance; and yet he is affectionately observed as though he were a mere mortal child asleep. In the darkness it is possible to make out his wings - he is not a young putto - and the quiver of arrows on which he sleeps, the bow with its broken string and the arrow, with a tinge of red, that he holds in his hand. In human affairs he plays a symbolic role.

Here Cupid is not in charge of fate. While forgetful Love sleeps on, lovers cannot cope with the clamorous demands of their passions, and they are lost. But even if Love has been vanquished in the past - his bowstring is broken - he has ammunition, the quiver and the arrows, with which he can fight again.

St. John the Baptist at the Well (1608)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist at the Well for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting does not fit into the artist's series of other St John the Baptist paintings. Only a few experts accept it as a genuine Caravaggio. Its colors are muted. A Banner with writing on it, which is wound around the unusually well-defined Jacob's staff on the ground, has an inscription which, although the artist twists it skilfully, can easily be read as: AGNUS DEI, the lamb of God. This painting possibly represents a late phase of the artist's creative work.

a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist at the Well for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting does not fit into the artist's series of other St John the Baptist paintings. Only a few experts accept it as a genuine Caravaggio. Its colors are muted. A Banner with writing on it, which is wound around the unusually well-defined Jacob's staff on the ground, has an inscription which, although the artist twists it skilfully, can easily be read as: AGNUS DEI, the lamb of God. This painting possibly represents a late phase of the artist's creative work.

Adoration of the Shepherds (1609)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Adoration of the Shepherds for your computer or notebook. ‣

While in Messina, Caravaggio was contracted to paint four scenes of the Passion. If he finished any of them, nothing now survives. This nativity scene, Susinno says, was ordered by the Senate of Messina for the Capuchin church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. A Franciscan simplicity pervades it: in the wooden barn a donkey and an ox stand patiently at the back, there is straw on the floor and in a basket the Holy Family have a loaf of bread, the carpenter's tools of Joseph and some pieces of cloth. Joseph (in red) introduces the shepherds, in brown and grey, to the young Virgin Mother, whose dress is a brighter red. Mary cuddles her baby peacefully and, apart from two haloes, only the bare-shouldered young man, who kneels with clasped hands, gives the moment of the child's discovery a hint of its meaning. God became man as one of the poor. Ironically, for this canvas Caravaggio received 1000 scudi, the highest amount mentioned in any accounts of his career.

a high-quality picture of

Adoration of the Shepherds for your computer or notebook. ‣

While in Messina, Caravaggio was contracted to paint four scenes of the Passion. If he finished any of them, nothing now survives. This nativity scene, Susinno says, was ordered by the Senate of Messina for the Capuchin church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. A Franciscan simplicity pervades it: in the wooden barn a donkey and an ox stand patiently at the back, there is straw on the floor and in a basket the Holy Family have a loaf of bread, the carpenter's tools of Joseph and some pieces of cloth. Joseph (in red) introduces the shepherds, in brown and grey, to the young Virgin Mother, whose dress is a brighter red. Mary cuddles her baby peacefully and, apart from two haloes, only the bare-shouldered young man, who kneels with clasped hands, gives the moment of the child's discovery a hint of its meaning. God became man as one of the poor. Ironically, for this canvas Caravaggio received 1000 scudi, the highest amount mentioned in any accounts of his career.

David (1609)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

David for your computer or notebook. ‣

Nobody knows which was Caravaggio's last work. This painting, which was in the collection of Scipione Borghese as early as 1613, has been dated as early as 1605 and as late as 1609-10. Its melancholy would suit the gloomy thoughts of the artist's final years. The subject matter recalls the Beheading of St John the Baptist in Valletta, but this time there is no brilliant colour and, as a small picture, it has an intimacy that was not evident in the grand public work.

a high-quality picture of

David for your computer or notebook. ‣

Nobody knows which was Caravaggio's last work. This painting, which was in the collection of Scipione Borghese as early as 1613, has been dated as early as 1605 and as late as 1609-10. Its melancholy would suit the gloomy thoughts of the artist's final years. The subject matter recalls the Beheading of St John the Baptist in Valletta, but this time there is no brilliant colour and, as a small picture, it has an intimacy that was not evident in the grand public work.

The boy handles his trophy with disgust. 'In that head [Caravaggio] wished to portray himself and in the boy he portrayed his Caravaggino,' wrote Manilli in 1650. If Goliath's head is indeed Caravaggio's, there is an element of self disgust in this painting. The device recalls the way that Michelangelo, in the Last Judgment for the Sistine Chapel, placed an anguished face with features evidently his own onto the flayed body of St Bartholomew, but Caravaggio's mood is closer to one of despair. As a witness to God's light, Bartholomew takes his seat in heaven: Goliath, God's enemy, is doomed to everlasting night.

Dirty silver, black and browns dominate the picture. The light shows David to look like a boy from the street, whose sword has just a drop of blood on it to show that, like Caravaggio once, he knows what it is to have just killed a man. Another drop of blood in the midst of the giant's forehead confirms that he has been felled by a stone.

A decade later Cardinal Scipione commissioned a statue of David about to catapult a stone at Goliath. Bernini was far removed from the anxieties of the older master, and saw David's action as joyful and exhilarating, a triumph of the human spirit expressing itself through the athletic exertions of a beautiful human body.

Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence (1609)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting representing the Nativity was stolen in October 1969 from the church of San Lorenzo in Palermo, where it had been since it was made. The composition is less successful than in other cases; the contained and pensive atmosphere, however, shows that at this stage Caravaggio associated the idea of advent of Christ not with the joy of Redemption but with a future that was at best uncertain.

a high-quality picture of

Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting representing the Nativity was stolen in October 1969 from the church of San Lorenzo in Palermo, where it had been since it was made. The composition is less successful than in other cases; the contained and pensive atmosphere, however, shows that at this stage Caravaggio associated the idea of advent of Christ not with the joy of Redemption but with a future that was at best uncertain.

Under the roof of the stable in Bethlehem, whose side walls are disappearing into brownish darkness, shepherds and saints gathered to worship the newborn Christ-child in such a way that we can make out Archdeacon Lawrence on the left only after a second look, and viewers may well mistake St Francis for a shepherd. One figure, the patron, represents the church for which the picture was intended, and the other, the Order to which the church belongs. We cannot be entirely sure who Joseph, the foster-father, is.

The center of the picture is shared out between the figures who have come to worship. The naked Christ-child lies there on a bed of straw and some white drapery. Exhausted, the Holy Virgin is crouching on the ground behind him - wearing an unusually cut dress, which is falling from her right shoulder - looking at the child. The ox, which appears behind St Lawrence, is also looking in that direction. Above all this, an angel is flying down from heaven. In his left hand he is holding a banner on which the words of the gloria are written. His right hand is pointing upwards, as if, by also looking at the baby, he wanted to reassure the Christ-child that he really is the Son of God.

Salome with the Head of the Baptist (1609)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Salome with the Head of the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting (which was earlier in the Casita del Principe, Escorial) was executed by Caravaggio to send to the Grand Master of Malta to appease him. It essentially follows the earlier version, today in London. The only slight change is in the pose of the executioner. And yet the two works are very obviously different. This later version rises out of an abyss of shadow. The executioner thoughtfully observes the result of his work, instead of lifting up the Baptist's head with certainty.

a high-quality picture of

Salome with the Head of the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting (which was earlier in the Casita del Principe, Escorial) was executed by Caravaggio to send to the Grand Master of Malta to appease him. It essentially follows the earlier version, today in London. The only slight change is in the pose of the executioner. And yet the two works are very obviously different. This later version rises out of an abyss of shadow. The executioner thoughtfully observes the result of his work, instead of lifting up the Baptist's head with certainty.

The Annunciation (1609)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Annunciation for your computer or notebook. ‣

Caravaggio painted church paintings during his last period in Naples. There is reason to believe that the artist's last altarpiece is the Annunciation that reached the high altar of the cathedral of Nancy in Lorrain just after the church was founded (1609). Today it is in the museum of that city.

a high-quality picture of

The Annunciation for your computer or notebook. ‣

Caravaggio painted church paintings during his last period in Naples. There is reason to believe that the artist's last altarpiece is the Annunciation that reached the high altar of the cathedral of Nancy in Lorrain just after the church was founded (1609). Today it is in the museum of that city.

Whether the painting was made in Sicily or in Naples is not known. Its style would seem to exclude earlier datings, for it is clearly a very late work. It has been pointed out that the angel comes into the painting from real space, canceling the separation between the picture and the viewer in a way typical of the Baroque aesthetic. The angel's face is practically invisible. The Virgin does not look at him, she is completely self-absorbed, her pose is devoid of joyous acceptance. She seems instead crushed by the expectation of an unbearable future. The spiritual testament that Caravaggio left us with this large, two-figural painting, where once again the Virgin is not distinguished by deifying attributes, is an infinite existential sadness, which seems to contain no hope of redemption.

The Raising of Lazarus (1609)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Raising of Lazarus for your computer or notebook. ‣

Most of Caravaggio's religious subjects emphasize sadness, suffering and death. In 1609 he dealt with the triumph of life and in doing so created the most visionary picture of his career.

a high-quality picture of

The Raising of Lazarus for your computer or notebook. ‣

Most of Caravaggio's religious subjects emphasize sadness, suffering and death. In 1609 he dealt with the triumph of life and in doing so created the most visionary picture of his career.

Lazarus, the brother of Martha and Mary, was the patron of Giovanni Battista de' Lazzari, to whom Caravaggio was contracted to paint an altarpiece in the church of the Padri Crociferi. The Gospel of St John tells how Lazarus fell sick, died, was buried and then miraculously raised from the dead by Christ.

Once again, the scene is set against blank walls that overwhelm the actors, who once more are laid out like figures on a frieze. Some of them, says Susinno, were modelled on members of the community, but at this stage Caravaggio did not have time to base himself wholly on models and relied on his memory - the whole design is based on an engraving after Giulio Romano and his Jesus is a reversed image of the Christ who called Matthew to join him.

There is a remarkable contrast between the flexible bodies of the grieving sisters and the near-rigid corpse of their brother. In the gospel Martha reminds Jesus that, as her brother had been dead four days, he would stink, but here nobody detracts from the dignity of the moment by holding his nose. Jesus is the resurrection and the life and in the darkness through him the truth is revealed.

The Tooth-Drawer (1609)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Tooth-Drawer for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting presents a plebeian and vulgar aspect of Caravaggio that we encounter in his life but not in his works. Consequently, the proposed attribution of this painting to Caravaggio met with much opposition. It must be pointed out, however, that even in the painting's unsatisfactory state of preservation (it was restored in an incompetent and harmful way, making it more difficult to study) an original quality of execution transpires that corresponds to the epitomized achievements of the late Caravaggio. It is also to be thought that there must have been a prototype, as so many of the works of Caravaggio's followers deal with this type of genre scene. The presence of a prototype in Naples would help explain some of the returns to this theme, including the late and striking works of the 18th century Neapolitan painter, Gaspare Traversi.

a high-quality picture of

The Tooth-Drawer for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting presents a plebeian and vulgar aspect of Caravaggio that we encounter in his life but not in his works. Consequently, the proposed attribution of this painting to Caravaggio met with much opposition. It must be pointed out, however, that even in the painting's unsatisfactory state of preservation (it was restored in an incompetent and harmful way, making it more difficult to study) an original quality of execution transpires that corresponds to the epitomized achievements of the late Caravaggio. It is also to be thought that there must have been a prototype, as so many of the works of Caravaggio's followers deal with this type of genre scene. The presence of a prototype in Naples would help explain some of the returns to this theme, including the late and striking works of the 18th century Neapolitan painter, Gaspare Traversi.

St. John the Baptist (1610)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting was executed during the last days of Caravaggio's stay in Naples, together with the Martyrdom of St Ursula.

a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting was executed during the last days of Caravaggio's stay in Naples, together with the Martyrdom of St Ursula.

A comparison can be made between the young St John in the Galleria Borghese in Rome and the paintings of the same subject in Kansas City and in the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Antica in Rome. The Borghese St John is the most soberly thoughtful. The body is delicate and the expression is dreamy, so much so as to suggest a considerable distance in time from the other two.

Caravaggio Art

|

|

More

Articles

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Baroque

Caravaggio

Art and life. Biography.

Early paintings by Caravaggio.

Late paintings by Caravaggio.

Art

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Caravaggio Art, $25

(100 pictures)

Rubens Art, $29

(200 pictures)

Rembrandt Art, $25

(160 pictures)