Art by Caravaggio

Caravaggio was an Italian painter whose revolutionary technique of

tenebrism, or dramatic, selective illumination of form out of deep

shadow, became a hallmark of Baroque painting. Caravaggio was the best

exemplar of naturalistic painting in the early 17th century.

Caravaggio was a "wild" and violent painter - screams of terror and

images of horror assume a prominent place in many of Caravaggio's

works.

Caravaggio was an Italian painter whose revolutionary technique of

tenebrism, or dramatic, selective illumination of form out of deep

shadow, became a hallmark of Baroque painting. Caravaggio was the best

exemplar of naturalistic painting in the early 17th century.

Caravaggio was a "wild" and violent painter - screams of terror and

images of horror assume a prominent place in many of Caravaggio's

works.

- Boy Peeling a Fruit (1593)

- Boy with a Basket of Fruit (1593)

- Sick Bacchus (1593)

- Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1594)

- St. Francis in Ecstasy (Detail) (1595)

- St. Francis in Ecstasy (1595)

- Still-Life with Flowers and Fruit (1595)

- Bacchus (1596)

- Lute Player (1596)

- The Cardsharps (1596)

- The Fortune Teller (1596)

- The Musicians (1596)

- Magdalene (1597)

- Rest on Flight to Egypt (Detail) (1597)

- Rest on Flight to Egypt (1597)

- The Fortune Teller (1597)

- Judith Beheading Holofernes (Detail) (1598)

- Judith Beheading Holofernes (1598)

- Martha and Mary Magdalene (1598)

- St. Catherine of Alexandria (1598)

- Taking of Christ (1598)

- Medusa (1599)

- Narcissus (1599)

- Portrait of Maffeo Barberini (1599)

- David (1600)

- St. John the Baptist (Youth with Ram) (1600)

- The Calling of Saint Matthew (Detail) (1600)

- The Calling of Saint Matthew (1600)

- The Conversion of St. Paul (1600)

- The Conversion on the Way to Damascus (Detail) (1600)

- The Conversion on the Way to Damascus (1600)

- The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (Detail) (1600)

- The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1600)

- The Lute Player (1600)

- The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (Detail) (1600)

- The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (1600)

Boy Peeling a Fruit (1593)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Boy Peeling a Fruit for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is probably a copy from a lost original. There are several other copies (e.g. in Hampton Court, in the Sabin collection, London) but all of these copies are derived from an original by Caravaggio. In none of them does the boy peel a pear, as sources indicate, but another fruit, perhaps a nectarine; the same fruit lies on the table before the boy. There is a remarkable resemblance between the facial types of these copies and those of the angel in the St Francis (Hartford) and the boy on the left in the Musicians at the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

a high-quality picture of

Boy Peeling a Fruit for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is probably a copy from a lost original. There are several other copies (e.g. in Hampton Court, in the Sabin collection, London) but all of these copies are derived from an original by Caravaggio. In none of them does the boy peel a pear, as sources indicate, but another fruit, perhaps a nectarine; the same fruit lies on the table before the boy. There is a remarkable resemblance between the facial types of these copies and those of the angel in the St Francis (Hartford) and the boy on the left in the Musicians at the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Boy with a Basket of Fruit (1593)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Boy with a Basket of Fruit for your computer or notebook. ‣

One of the sure signs of an early painting by Caravaggio is the patent influence of northern Italian art. The boy with a fruit basket has analogies with a Fruitseller by the Lombard painter Vincenzo Campi, painted about 1580, but Caravaggio is not content to follow the traditions on which he draws. Instead of the young women favoured by his predecessors, he has chosen a teenage boy; and he has brought his subject almost to the front of the picture plane, so that the boy seems to offer himself as well as the fruit to the spectator's gaze. There is a sign of uncertainty in the awkward way that the boy's long thick neck rises out of his shoulder blades, yet there is compensation in the poetic device which places his weary eyes partially in the shade. Once again Caravaggio has used the diagonal 'cellar' light which was to become a hallmark of his style. Against a near-blank ground, attention is focused on the right side of the boy's upper body, the classical drapery on his right arm and the marvellously realized fruit, displaying succulent peaches and bunches of grapes.

a high-quality picture of

Boy with a Basket of Fruit for your computer or notebook. ‣

One of the sure signs of an early painting by Caravaggio is the patent influence of northern Italian art. The boy with a fruit basket has analogies with a Fruitseller by the Lombard painter Vincenzo Campi, painted about 1580, but Caravaggio is not content to follow the traditions on which he draws. Instead of the young women favoured by his predecessors, he has chosen a teenage boy; and he has brought his subject almost to the front of the picture plane, so that the boy seems to offer himself as well as the fruit to the spectator's gaze. There is a sign of uncertainty in the awkward way that the boy's long thick neck rises out of his shoulder blades, yet there is compensation in the poetic device which places his weary eyes partially in the shade. Once again Caravaggio has used the diagonal 'cellar' light which was to become a hallmark of his style. Against a near-blank ground, attention is focused on the right side of the boy's upper body, the classical drapery on his right arm and the marvellously realized fruit, displaying succulent peaches and bunches of grapes.

Sick Bacchus (1593)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Sick Bacchus for your computer or notebook. ‣

Among Caravaggio's early works, this painting, in which the pose of the arm may recall his debt to the kneeling shepherd in a fresco by Peterzano, belongs to the small group which has always been seen as self-portraits. The livid colours of the subject's face, his teasing smile and the mock seriousness of his mythological dignity all reinforce the attempt to undermine the lofty pretensions of Renaissance artistic traditions. Here is no god, just a sickly young man who may be suffering from the after-effects of a hangover. There is no mistaking the artist's delight in the depiction of the fine peaches and black grapes on the slab, the white grapes in his hand and the vine leaves that crown his hair, but the artist is not content merely to demonstrate his superb technique: he wishes to play an intimate role and only the slab separates him from the viewer. His appearance is striking rather than handsome: he shows both that his face is unhealthy and that his right shoulder is not that of a bronzed Adonis, as convention required, but pale as in the case of any man who normally wears clothes.

a high-quality picture of

Sick Bacchus for your computer or notebook. ‣

Among Caravaggio's early works, this painting, in which the pose of the arm may recall his debt to the kneeling shepherd in a fresco by Peterzano, belongs to the small group which has always been seen as self-portraits. The livid colours of the subject's face, his teasing smile and the mock seriousness of his mythological dignity all reinforce the attempt to undermine the lofty pretensions of Renaissance artistic traditions. Here is no god, just a sickly young man who may be suffering from the after-effects of a hangover. There is no mistaking the artist's delight in the depiction of the fine peaches and black grapes on the slab, the white grapes in his hand and the vine leaves that crown his hair, but the artist is not content merely to demonstrate his superb technique: he wishes to play an intimate role and only the slab separates him from the viewer. His appearance is striking rather than handsome: he shows both that his face is unhealthy and that his right shoulder is not that of a bronzed Adonis, as convention required, but pale as in the case of any man who normally wears clothes.

Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1594)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Boy Bitten by a Lizard for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture is wrongly said by Mancini not to be one of Caravaggio's earliest pictures, and since he also states that the picture was sold for less than Caravaggio expected, it must have been painted as a speculative venture.

a high-quality picture of

Boy Bitten by a Lizard for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture is wrongly said by Mancini not to be one of Caravaggio's earliest pictures, and since he also states that the picture was sold for less than Caravaggio expected, it must have been painted as a speculative venture.

One of the most effeminate of his boy models, with a rose in his hair, starts back in pain as his right-hand middle finger, which he has put into a cluster of fruit, is bitten by a lizard. The rose behind the ear, the cherries, the third finger and the lizard probably have sexual significance - the boy becomes aware, with a shock, of the pains of physical love. What was novel was not the theme so much as its dramatic treatment, evident in the boy's foreshortened right shoulder, the contrasting gestures of his hands and the leftward sloping light. What lingers most in the memory is found in the foreground: the gleaming glass carafe containing a single overblown rose in water, together with its reflections.

Two almost identical examples of this composition exist (the other in the Longhini Collection, Florence). Their equally high quality suggests that Caravaggio himself painted them both.

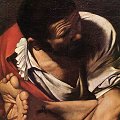

St. Francis in Ecstasy (Detail) (1595)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Francis in Ecstasy (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The angel comes from the same repertoire as the early pictures of boys. As Cupid, he is familiar from the New York Musicians. In the St Francis scene he forms part of an arrangement set against an almost black background, which may well have been painted direct from life and transmutes the spirit of pictures of boys into the sphere of sacred art.

a high-quality picture of

St. Francis in Ecstasy (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The angel comes from the same repertoire as the early pictures of boys. As Cupid, he is familiar from the New York Musicians. In the St Francis scene he forms part of an arrangement set against an almost black background, which may well have been painted direct from life and transmutes the spirit of pictures of boys into the sphere of sacred art.

St. Francis in Ecstasy (1595)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Francis in Ecstasy for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is one of the artist's first works. It has a perfectly Lombard air: the broad lines of the composition recall mannerist motives. But Caravaggio's characteristic approach to reality is already at work, and his brushstroke shows a magic that could be obtained only by a thorough analysis of Venetian painting.

a high-quality picture of

St. Francis in Ecstasy for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is one of the artist's first works. It has a perfectly Lombard air: the broad lines of the composition recall mannerist motives. But Caravaggio's characteristic approach to reality is already at work, and his brushstroke shows a magic that could be obtained only by a thorough analysis of Venetian painting.

Still-Life with Flowers and Fruit (1595)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Still-Life with Flowers and Fruit for your computer or notebook. ‣

From a thematic point of view, large scale still-lifes in the Galleria Borghese are similar to outstanding early works by Caravaggio, but they lack the brilliance and the concentration on individual objects. This painting and another are usually attributed to Caravaggio. Because it is rather unconvincing to attribute such work to Caravaggio, some scholars distinguish this Caravaggesque painter of still-lifes from the master by naming him - after a splendid example of the genre - the Painter of the Still-Life in the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford.

a high-quality picture of

Still-Life with Flowers and Fruit for your computer or notebook. ‣

From a thematic point of view, large scale still-lifes in the Galleria Borghese are similar to outstanding early works by Caravaggio, but they lack the brilliance and the concentration on individual objects. This painting and another are usually attributed to Caravaggio. Because it is rather unconvincing to attribute such work to Caravaggio, some scholars distinguish this Caravaggesque painter of still-lifes from the master by naming him - after a splendid example of the genre - the Painter of the Still-Life in the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford.

Bacchus (1596)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Bacchus for your computer or notebook. ‣

In order to understand the historical position of Caravaggio's art, we have to be aware of his peerless and revolutionary handling of subject matter. This is true not only of his religious themes, but also of his secular themes. His Bacchus no longer appears to us like an ancient god, or the Olympian vision of the High Renaissance and Mannerism. Instead, Caravaggio paints a rather vulgar and effeminately preened youth, who turns his plump face towards us and offers us wine from a goblet held by pertly cocked fingers with grimy nails. This is not Bacchus himself, but some perfectly ordinary individual dressed up as Bacchus, who looks at us rather wearily and yet alertly.

a high-quality picture of

Bacchus for your computer or notebook. ‣

In order to understand the historical position of Caravaggio's art, we have to be aware of his peerless and revolutionary handling of subject matter. This is true not only of his religious themes, but also of his secular themes. His Bacchus no longer appears to us like an ancient god, or the Olympian vision of the High Renaissance and Mannerism. Instead, Caravaggio paints a rather vulgar and effeminately preened youth, who turns his plump face towards us and offers us wine from a goblet held by pertly cocked fingers with grimy nails. This is not Bacchus himself, but some perfectly ordinary individual dressed up as Bacchus, who looks at us rather wearily and yet alertly.

On the one hand, by turning this heathen figure into a somewhat ambiguous purveyor of pleasures, Caravaggio is certainly the great realist he is always claimed to be. On the other hand, however, the sensual lyricism of his painting is so overwhelming that any suspicion of caricature or travesty would be inappropriate.

Lute Player (1596)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Lute Player for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting, mentioned in Del Monte's inventory, shows a single lutanist singing a love song; and a related 'carafe with flowers' is also listed in the catalogue of the Del Monte sale. From the seventeenth century there have been uncertainties about the gender of the singer. Baglione and the Del Monte inventory call him a boy; Bellori, who knew only a copy, calls him a girl. There are reasons for this confusion. One is the Renaissance fascination with androgyny - the singer is not much older than Shakespeare's Rosalind, who renamed herself Ganymede, and Viola, who renamed herself Cesario - and another is the Italian fashion for castrati. The lutanist, with parted lips, sings of love from the madrigal Voi sapete ch ['io v'amo] (you know that [I love you]) by the Flemish composer Arcadelt. In front of him are a violin and bow which invite the spectator to take part in a duet with him; the fruit and the vegetables, and indeed the music itself, imply the harmony that should exist between lovers.

a high-quality picture of

Lute Player for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting, mentioned in Del Monte's inventory, shows a single lutanist singing a love song; and a related 'carafe with flowers' is also listed in the catalogue of the Del Monte sale. From the seventeenth century there have been uncertainties about the gender of the singer. Baglione and the Del Monte inventory call him a boy; Bellori, who knew only a copy, calls him a girl. There are reasons for this confusion. One is the Renaissance fascination with androgyny - the singer is not much older than Shakespeare's Rosalind, who renamed herself Ganymede, and Viola, who renamed herself Cesario - and another is the Italian fashion for castrati. The lutanist, with parted lips, sings of love from the madrigal Voi sapete ch ['io v'amo] (you know that [I love you]) by the Flemish composer Arcadelt. In front of him are a violin and bow which invite the spectator to take part in a duet with him; the fruit and the vegetables, and indeed the music itself, imply the harmony that should exist between lovers.

Among the early works this painting must count as a virtuoso performance. The glass carafe and its flowers are painted with assured mastery, and Caravaggio is also aware of the problems of perspective that lutes and violins could cause; and he spotlights the the solo player and his instruments so as to make them the main focus of attention, the carafe of flowers so that they are a secondary focus. One of his most talented followers, Orazio Gentileschi, was to paint a girl lutanist with a more beguiling sense of poetry, but without the sense of immediacy that was the hallmark of his master's craft.

The Cardsharps (1596)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Cardsharps for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Cardsharps, lost for almost a century, has been found and is now in Texas, and helps to fill in an important stage in the development of Caravaggio's art. Behind a table that protrudes into the spectator's space, a youthful innocent studies his cards, overlooked by a sinister middle-aged man, whose fingers signal to another, younger scoundrel to his right, who holds a five of hearts behind his back. To the left-hand side of the canvas is the object of their conspiracy, a pile of coins.

a high-quality picture of

The Cardsharps for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Cardsharps, lost for almost a century, has been found and is now in Texas, and helps to fill in an important stage in the development of Caravaggio's art. Behind a table that protrudes into the spectator's space, a youthful innocent studies his cards, overlooked by a sinister middle-aged man, whose fingers signal to another, younger scoundrel to his right, who holds a five of hearts behind his back. To the left-hand side of the canvas is the object of their conspiracy, a pile of coins.

This low-life scene links Caravaggio's discreet dramas to the genre paintings favoured by his followers. It was to have many imitators - within a few years of the painter's death an early variant had been painted by the Franco-Roman Valentin de Boulogne - but few equals. Caravaggio was less melodramatic than many of the artists known as the Caravaggisti who painted in his style, and he suggests only enough of the interaction between the three actors to imply the sequel.

The Fortune Teller (1596)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Fortune Teller for your computer or notebook. ‣

The youth abandons his reserve, leans over towards the gypsy-woman and looks into her smiling face, as if he idolized her, and as if the woman was enticing a very willing man. We cannot be absolutely sure this picture is an original Caravaggio. Its authenticity has recently been based on two arguments. The genre-scene has been painted over a praying female saint, perhaps the Virgin Mary, and the most likely painter is the Cavaliere d'Arpino. The painting also carries the same indication of provenance from Cardinal del Monte's Collection as the Cardsharps. The same subject-matter recurs in Narcissus. In the case of this not-undisputed picture, the smooth way in which the paint is applied suggests a Caravaggesque artist of some note.

a high-quality picture of

The Fortune Teller for your computer or notebook. ‣

The youth abandons his reserve, leans over towards the gypsy-woman and looks into her smiling face, as if he idolized her, and as if the woman was enticing a very willing man. We cannot be absolutely sure this picture is an original Caravaggio. Its authenticity has recently been based on two arguments. The genre-scene has been painted over a praying female saint, perhaps the Virgin Mary, and the most likely painter is the Cavaliere d'Arpino. The painting also carries the same indication of provenance from Cardinal del Monte's Collection as the Cardsharps. The same subject-matter recurs in Narcissus. In the case of this not-undisputed picture, the smooth way in which the paint is applied suggests a Caravaggesque artist of some note.

The Musicians (1596)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Musicians for your computer or notebook. ‣

The two figures seen frontally are undoubtably portraits, and this fact disorients those who would like to make a conventional reading of the scene and concentrate on the noble, classical character of the composition, organized around the traditional opposition between the figure of the lute player and the corresponding figure whom we see from behind. The face between these two is Caravaggio's; the figure on the left is taken from an earlier composition (Young Peeling a Pear) which we know only from copies.

a high-quality picture of

The Musicians for your computer or notebook. ‣

The two figures seen frontally are undoubtably portraits, and this fact disorients those who would like to make a conventional reading of the scene and concentrate on the noble, classical character of the composition, organized around the traditional opposition between the figure of the lute player and the corresponding figure whom we see from behind. The face between these two is Caravaggio's; the figure on the left is taken from an earlier composition (Young Peeling a Pear) which we know only from copies.

Magdalene (1597)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Magdalene for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture and The Rest on the Flight into Egypt must have been painted around the same time, for the same girl sat for the Magdalene and the Madonna. On this occasion, however, there are none of the usual signs of a religious scene such as a halo. A young girl, seen from above, is seated on a low stool in one of Caravaggio's favourite cave-like settings, with a triangle of light high up on the wall behind her. Discarded jewellery - a string of pearls, clasps, a jar (perhaps holding precious ointment) - lies on the floor. The girl's hair is loose, as if it has just been washed. Her costume, consisting of a white-sleeved blouse, a yellow tunic and a flowery skirt, is rich. Bellori, who gives a careful description of this picture, which he came across in the collection of Prince Pamphilj, regards its title as an excuse; for him it is just a naturalistic portrayal of a pretty girl. This seems to show a willful failure to understand Caravaggio's intention or the wishes of the man who commissioned it, Monsignor Petrignani. The repentant Mary Magdalene, like the repentant Peter, was a favourite subject of Counter-Reformation art and poetry, which valued the visible expression of the state of contrition 'the gift of tears'. Caravaggio's heroine is sobbing silently to herself and a single tear falls down her cheek. She is, as it were, poised between her past life of luxury and the simple life she will embrace as one of Christ's most faithful followers. It is a sign of the painter's skill that he makes this inner conflict moving at the same time as he makes its representation delectable.

a high-quality picture of

Magdalene for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture and The Rest on the Flight into Egypt must have been painted around the same time, for the same girl sat for the Magdalene and the Madonna. On this occasion, however, there are none of the usual signs of a religious scene such as a halo. A young girl, seen from above, is seated on a low stool in one of Caravaggio's favourite cave-like settings, with a triangle of light high up on the wall behind her. Discarded jewellery - a string of pearls, clasps, a jar (perhaps holding precious ointment) - lies on the floor. The girl's hair is loose, as if it has just been washed. Her costume, consisting of a white-sleeved blouse, a yellow tunic and a flowery skirt, is rich. Bellori, who gives a careful description of this picture, which he came across in the collection of Prince Pamphilj, regards its title as an excuse; for him it is just a naturalistic portrayal of a pretty girl. This seems to show a willful failure to understand Caravaggio's intention or the wishes of the man who commissioned it, Monsignor Petrignani. The repentant Mary Magdalene, like the repentant Peter, was a favourite subject of Counter-Reformation art and poetry, which valued the visible expression of the state of contrition 'the gift of tears'. Caravaggio's heroine is sobbing silently to herself and a single tear falls down her cheek. She is, as it were, poised between her past life of luxury and the simple life she will embrace as one of Christ's most faithful followers. It is a sign of the painter's skill that he makes this inner conflict moving at the same time as he makes its representation delectable.

Although nothing painted in the sixteenth century is as emotive as the statue in wood of the haggard saint carved by Donatello (c.1456-60), by the time Titian's bare-breasted Magdalene of the 1530s (Palazzo Pitti, Florence) had become the more modest and affecting Magdalene of the 1560s, there had been a move in religious sensibility towards the humble and pathetic, a change which thirty years later Caravaggio could take for granted.

Rest on Flight to Egypt (Detail) (1597)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Rest on Flight to Egypt (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The composition fans out from an exquisite angel who is playing music. Joseph is wearing clothes of earth-color and is holding a book of music, from which the angel is playing a violin solo, whilst the donkey's large eyes peeps out from under the brown foliage.

a high-quality picture of

Rest on Flight to Egypt (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The composition fans out from an exquisite angel who is playing music. Joseph is wearing clothes of earth-color and is holding a book of music, from which the angel is playing a violin solo, whilst the donkey's large eyes peeps out from under the brown foliage.

The Angel is playing a motet in honour of the Madonna, Quam pulchra es..., composed by Noul Bauldewijn to the words of the Song of Songs (7,7) with the dialogue between Groom and Bride (understood in the painting not so much as Joseph and Mary, but as Jesus Christ and the Madonna, i.e. the church): "How fair and pleasant art thou, O love, for delights! This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters of grapes." In the Gospel according to the pseudo-Matthew (20,1), significantly dedicated to the Flight into Egypt, the same metaphorical image of the palm tree laden with fruit returns.

The principal motif of Caravaggio's Flight into Egypt is that of the music that can be heard on earth, considered by the Fathers of the Church to be a copy of music in heaven. The intermediary between these two worlds is the invisible sound, which in art takes the form of an Angel playing music, a divine messenger that stands at the border between material and spiritual reality. God communicates with men through Angels, who are his go-betweens: "[it is the] Angel who spoke to me," says Zachariah and for Ezekiel, the Angel is "the man dressed in linen," just as Caravaggio depicts him.

Rest on Flight to Egypt (1597)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Rest on Flight to Egypt for your computer or notebook. ‣

The story of the Holy Family's flight was one of the most popular apocryphal legends which survived the prohibitive decrees of the Council of Trent and often appeared in painting from the end of the sixteenth century. Caravaggio's idyllic painting is an individualistic representation of this.

a high-quality picture of

Rest on Flight to Egypt for your computer or notebook. ‣

The story of the Holy Family's flight was one of the most popular apocryphal legends which survived the prohibitive decrees of the Council of Trent and often appeared in painting from the end of the sixteenth century. Caravaggio's idyllic painting is an individualistic representation of this.

The artist ingeniously uses the figure of an angel playing the violin with his back to the viewer to divide the composition into two parts. On the right, before an autumnal river-front scene, we can see the sleeping Mary with a dozing infant in her left; on the left, a seated Joseph holding the musical score for the angel. The natural surroundings reminds the viewer of the Giorgionesque landscapes of the Cinquecento masters of Northern Italian painting, and it is fully imbued with a degree of nostalgia. Contrasting the unlikelihood of the event is the realistic effect of depiction, the accuracy of details, the trees, the leaves and stones, whereby the total impression becomes astonishingly authentic. The statue-like figure of the angel, with a white robe draped around him, is like a charmingly shaped musical motif, and it provides the basic tone for the composition. It is an interesting contradiction - and at the same time a good example for the adaptability of forms - that this figure of pure classical beauty is a direct descendant of Annibale Carracci's Luxuria from the painting "The Choice of Heracles".

It has not been clearly decided what was the textual source for the music-playing angel in the story of the flight into Egypt. Charming is Caravaggio's decision to actively involve St Joseph in the music-making.

The Fortune Teller (1597)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Fortune Teller for your computer or notebook. ‣

With The Fortune Teller (La Zingara), Caravaggio introduced, around 1594/95, a subject into Italian painting that was known, if at all, only in Netherlandish paintings: the so-called genre, depicting scenes of everyday life, but with a hidden or underlying meaning intended for the edification of the observant spectator. Two themes from Caravaggio's early years can be placed in the category of genre painting: one representing a card game is unfortunately lost, the other is the Fortune Teller. This theme is preserved in two paintings both of which are probably original. The other painting is in the Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome.

a high-quality picture of

The Fortune Teller for your computer or notebook. ‣

With The Fortune Teller (La Zingara), Caravaggio introduced, around 1594/95, a subject into Italian painting that was known, if at all, only in Netherlandish paintings: the so-called genre, depicting scenes of everyday life, but with a hidden or underlying meaning intended for the edification of the observant spectator. Two themes from Caravaggio's early years can be placed in the category of genre painting: one representing a card game is unfortunately lost, the other is the Fortune Teller. This theme is preserved in two paintings both of which are probably original. The other painting is in the Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome.

A foppishly dressed young man, a milksop with no experience of life, gives his right hand to a young girl whose expression is difficult to define, in order to have his future read. His ideas about his future are effectively influenced by the astute young gypsy girl, whose gentle caress in tracing the lines of his hand captivates the handsome young fool so completely that he fails to notice his ring being drawn from his finger. This anecdotal narrative could be further embroidered, and indeed the painting invites us to do so as much through the plot it portrays as through what it tells us of the two characters by way of their clothing. The feathered hat, the gloves and the showy, oversized dagger immediately tell us who we are dealing with here. Similarly, the gypsy girl with her light linen shirt and her exotic wrap is intended as a "type" rather than as an individual person.

This means, of course, that what we have here is not an anecdote of two specific people, but an everyday tale. No specification of place or time detracts our attention from the point of the story, which gives the spectator a sense of complacent superiority as well as aesthetic pleasure.

Judith Beheading Holofernes (Detail) (1598)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Judith Beheading Holofernes (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Judith was painted directly from a model, as the suntan on her hands and face attests. The well turned-out blond woman with her full breasts, which remain visible through her white blouse, has rolled her sleeves up over her elbows. She stretches out her strong arm, but draws her head back, as if she were repulsed by blood. The Borghese David behaves in a similar fashion.

a high-quality picture of

Judith Beheading Holofernes (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Judith was painted directly from a model, as the suntan on her hands and face attests. The well turned-out blond woman with her full breasts, which remain visible through her white blouse, has rolled her sleeves up over her elbows. She stretches out her strong arm, but draws her head back, as if she were repulsed by blood. The Borghese David behaves in a similar fashion.

Judith Beheading Holofernes (1598)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Judith Beheading Holofernes for your computer or notebook. ‣

A whole book in the Bible is devoted to Judith, because as a woman she embodies the power of the people of Israel to defeat the enemy, though superior in numbers, by means of cunning and courage. She seeks out Holofernes in his tent, makes him drunk, then beheads him. The sight of their commander's bloodstained head on the battlements of Bethulia puts the enemy to flight.

a high-quality picture of

Judith Beheading Holofernes for your computer or notebook. ‣

A whole book in the Bible is devoted to Judith, because as a woman she embodies the power of the people of Israel to defeat the enemy, though superior in numbers, by means of cunning and courage. She seeks out Holofernes in his tent, makes him drunk, then beheads him. The sight of their commander's bloodstained head on the battlements of Bethulia puts the enemy to flight.

In the painting, Judith comes in with her maid - surprisingly and menacingly - from the right, against the direction of reading the picture. The general is lying naked on a white sheet. Paradoxically, his bed is distinguished by a magnificent red curtain, whose colour crowns the act of murder as well as the heroine's triumph.

The first instance in which Caravaggio would chose such a highly dramatic subject, the Judith is an expression of an allegorical-moral contest in which Virtue overcomes Evil. In contrast to the elegant and distant beauty of the vexed Judith, the ferocity of the scene is concentrated in the inhuman scream and the body spasm of the giant Holofernes. Caravaggio has managed to render, with exceptional efficacy, the most dreaded moment in a man's life: the passage from life to death. The upturned eyes of Holofernes indicate that he is not alive any more, yet signs of life still persist in the screaming mouth, the contracting body and the hand that still grips at the bed. The original bare breasts of Judith, which suggest that she has just left the bed, were later covered by the semi-transparent blouse.

The roughness of the details and the realistic precision with which the horrific decapitation is rendered (correct down to the tiniest details of anatomy and physiology) has led to the hypothesis that the painting was inspired by two highly publicized contemporary Roman executions; that of Giordano Bruno and above all of Beatrice Cenci in 1599.

Martha and Mary Magdalene (1598)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Martha and Mary Magdalene for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting has an iconographically very unusual theme. It shows Martha reproaching Mary Magdalene for her vanity, a subject that we know through a series of copies. The painting at Detroit has recently been recognized as the original.

a high-quality picture of

Martha and Mary Magdalene for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting has an iconographically very unusual theme. It shows Martha reproaching Mary Magdalene for her vanity, a subject that we know through a series of copies. The painting at Detroit has recently been recognized as the original.

The religious theme is treated in a substantially profane manner. It is a pretext for making passages of highly intensive painting and for constructing an image that, seen in the context of the usual dichotomy of Caravaggio's early years, is more of a genre scene than a religious one.

St. Catherine of Alexandria (1598)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Catherine of Alexandria for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting formerly belonged to Cardinal Del Monte, one of the artist's patrons.

a high-quality picture of

St. Catherine of Alexandria for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting formerly belonged to Cardinal Del Monte, one of the artist's patrons.

Here we see a single female figure in an interior devoid of architectural allusions. The image appears with a boldness and an immediacy that combine the nobility of the subject (St Catherine was a king's daughter) with the almost plebeian pride of the model (no doubt a Roman woman of the people, who appears on other paintings of the artist, too). The breadth of conception and realization, and the perfect mastery of a very difficult composition (the figure and objects completely fill the painting, in a subtle play of diagonals) are striking. Caravaggio here chose a "grand" noble approach that heralds the great religious compositions he would soon do for San Luigi dei Francesi. The extraordinary virtuosity in the painting of the large, decorated cloth is absorbed as an integral part of the composition. This is something his followers would not often succeed in doing, for they frequently dealt with the single components of the painting individually, with adverse effects on the unity of the whole.

Taking of Christ (1598)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Taking of Christ for your computer or notebook. ‣

The attribution of the painting is doubtful. Another version of this subject is in the Museum of Western and Eastern Art, Odessa.

a high-quality picture of

Taking of Christ for your computer or notebook. ‣

The attribution of the painting is doubtful. Another version of this subject is in the Museum of Western and Eastern Art, Odessa.

The main figures are pushed to the left, so that the right-hand half of the picture is left to the soldiers, whose suits of armor absorb what little light there is, and whose faces are the most part hidden. At the right of the picture, an unhelmeted head emerges from the surrounding darkness. This is often regarded as the artist's self-portrait. Caravaggio has also concerned himself here with the act of seeing as one of a painter's task. The three men on the right are there mainly to intensify the visual core of the painting, underscored by the lantern. On the left, the tactile aspect is not forgotten. Judas vigorously embraces his master, whilst a heavily mailed arm reaches above him towards Christ's throat. Christ, however, crosses his hands, which he holds out well in front of him, whilst St John flees shrieking into the deep night. His red cloak is torn from his shoulder. As it flaps open it binds the faces of Christ and Judas together - a deliberate touch on the artist's part.

Medusa (1599)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Medusa for your computer or notebook. ‣

In Greek myth, Perseus used the severed snake-haired head of the Gorgon Medusa as a shield with which to turn his enemies to stone. By the sixteenth century Medusa was said to symbolize the triumph of reason over the senses; and this may have been why Cardinal Del Monte commissioned Caravaggio to paint Medusa as the figure on a ceremonial shield presented in 1601 to Ferdinand I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The poet Marino claimed that it symbolized the Duke's courage in defeating his enemies.

a high-quality picture of

Medusa for your computer or notebook. ‣

In Greek myth, Perseus used the severed snake-haired head of the Gorgon Medusa as a shield with which to turn his enemies to stone. By the sixteenth century Medusa was said to symbolize the triumph of reason over the senses; and this may have been why Cardinal Del Monte commissioned Caravaggio to paint Medusa as the figure on a ceremonial shield presented in 1601 to Ferdinand I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The poet Marino claimed that it symbolized the Duke's courage in defeating his enemies.

As a feat of perspective, the picture is remarkable, for out of the apparently concave surface of the shield - in fact convex- the Gorgon's head seems to project into space, so that the blood round her neck appears to fall on the floor. In terms of its psychology, however, it is less successful. The boy who modelled the face (in preference to a girl) is more embarrassed than terrifying. For once Caravaggio cannot achieve an effect of horror; he was to find in the legends of the martyrs a more powerful stimulus to the dark side of his imagination than classical myth.

Narcissus (1599)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Narcissus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The attribution of this painting to Caravaggio has been discussed at length and it is still questioned by some scholars. There are no contemporary sources to refer to, and the attribution rests entirely on stylistic bases.

a high-quality picture of

Narcissus for your computer or notebook. ‣

The attribution of this painting to Caravaggio has been discussed at length and it is still questioned by some scholars. There are no contemporary sources to refer to, and the attribution rests entirely on stylistic bases.

The theory that the picture is by Caravaggio might be confirmed by an export license dating to 1645, referring to a Narcissus by Caravaggio of similar measurements to our canvas. While it is difficult to propose with absolute certainty a secure connection between the document and the present canvas, several major Caravaggio scholars have reconsidered the issue, accepted the link between the license and the painting, and confirmed the autograph quality of the work.

Analysis of the details of execution (carried out as part of a recent restoration), stylistic comparison to other works of Caravaggio, and the iconographic innovativeness of the subject all lead to acceptance of the Narcissus as a work of Caravaggio. On the subject of invention, it suffices to mention the exceptional the double figure which - like a playing card - turns on the fulcrum of the highlit knee at the centre of the composition.

The work belongs to the years between 1597 and 1599, a transitional period of Caravaggio's career that is still not entirely sorted out or fully understood. It is a moment in which Caravaggio tended towards a magical sense of atmosphere, suspense, and introspection: still strongly influenced by the Lombard style of Moretto and Savoldo, he is also testing the infinite possibilities of light and shadow. Dating from the same phase of Caravaggio's career are the Lute Player, the Doria Magdalene, and above all the Thyssen St Catherine and Detroit Magdalene, with which our canvas has many connections and resonances.

Portrait of Maffeo Barberini (1599)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Maffeo Barberini for your computer or notebook. ‣

The still undeveloped features of this young cleric, who later became Pope Urban VIII (1623-1644) were portrayed as a much more distinguished figure by the skills of Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). Here, the face appears in chiaroscuro against a neutral background in such a way that a wall appears to be screening off the figure from the left. In order to give the figure more 'rilievo', or more three-dimensionality, the lit sections are painted against a dark, and the sections in shadow against a light, background.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Maffeo Barberini for your computer or notebook. ‣

The still undeveloped features of this young cleric, who later became Pope Urban VIII (1623-1644) were portrayed as a much more distinguished figure by the skills of Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). Here, the face appears in chiaroscuro against a neutral background in such a way that a wall appears to be screening off the figure from the left. In order to give the figure more 'rilievo', or more three-dimensionality, the lit sections are painted against a dark, and the sections in shadow against a light, background.

David (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

David for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting addresses the subject of David and Goliath, which the artist repeatedly dealt with later in his career, with a perfect linearity of means and intelligence of iconographic invention. As in the early Renaissance, David is shown as the adolescent who triumphs not by his strength, but by his power of character and his faith. The oblique pose of the figure (David stands partly parallel to the picture plane) is constructed with admirable skill.

a high-quality picture of

David for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting addresses the subject of David and Goliath, which the artist repeatedly dealt with later in his career, with a perfect linearity of means and intelligence of iconographic invention. As in the early Renaissance, David is shown as the adolescent who triumphs not by his strength, but by his power of character and his faith. The oblique pose of the figure (David stands partly parallel to the picture plane) is constructed with admirable skill.

Caravaggio has a particular importance for Spain, for he originated the realist and 'tenebrist' style of painting that enjoyed such development and popularity there in the work of such artists as Ribera and Zurbaran. This mature work demonstrates the fundamentals of his art: an emphatic solidity created by a harsh contrast of light and shade; the immediacy created by staging the action right in the foreground, and eliminating all superfluous space around it (conventionally, David would have been given room to stand up, so to speak); the elimination of decoration, such as colour or elegant posture, in order to concentrate on the drama alone.

St. John the Baptist (Youth with Ram) (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist (Youth with Ram) for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting exists in two versions, both of which are probably by Caravaggio (who frequently copied his own paintings). Both versions are in Rome, the other in the Galleria Doria-Pamphili.

a high-quality picture of

St. John the Baptist (Youth with Ram) for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting exists in two versions, both of which are probably by Caravaggio (who frequently copied his own paintings). Both versions are in Rome, the other in the Galleria Doria-Pamphili.

The image is a masterpiece of virtuosity whose appeal lies in its soft, caressing light and velvety rendering of cloth, flesh, and plants. The figure is identifiable as St. John only virtue of the symbols of Christ displayed in the painting: the ram (sacrificial victim), and the grape-leaves (from whose red juice, akin to the blood of Christ, springs life); otherwise the iconographical subject (the simple, immediately apparent image) appears as a nude youth with an ironic, if not allusive, expression. Its cultivated content and its destination for an aristocratic patron are underscored by the artist's explicit use of a great figurative source of the past: Michelangelo's Ignudi from the Sistine Ceiling. But whereas Michelangelo created abstract and ideal figures with cold lights and a merely theoretical plasticism, Caravaggio models his figure on the careful observation of nature, achieving an image of perfect realism.

The Calling of Saint Matthew (Detail) (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Calling of Saint Matthew (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

On the right, two youths are sitting opposite each other. The younger one, more strongly lit, is leaning back, putting his arm on St Matthew's shoulder for protection. The youth opposite, with his sword dangling against his upper tigh, spreads out his legs as he turns right.

a high-quality picture of

The Calling of Saint Matthew (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

On the right, two youths are sitting opposite each other. The younger one, more strongly lit, is leaning back, putting his arm on St Matthew's shoulder for protection. The youth opposite, with his sword dangling against his upper tigh, spreads out his legs as he turns right.

The Calling of Saint Matthew (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Calling of Saint Matthew for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting is the pendant to the Martyrdom of St Matthew and hanging opposite in the Contarelli Chapel of the San Luigi dei Francesi, the French Church in Rome. It was particularly appropriate to both the place and the time, for Rome's French community had something to celebrate: Henri IV, heir to St Louis, had recently converted to the faith of his ancestors.

a high-quality picture of

The Calling of Saint Matthew for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting is the pendant to the Martyrdom of St Matthew and hanging opposite in the Contarelli Chapel of the San Luigi dei Francesi, the French Church in Rome. It was particularly appropriate to both the place and the time, for Rome's French community had something to celebrate: Henri IV, heir to St Louis, had recently converted to the faith of his ancestors.

The subject traditionally was represented either indoors or out; sometimes Saint Matthew is shown inside a building, with Christ outside (following the Biblical text) summoning him through a window. Both before and after Caravaggio the subject was often used as a pretext for anecdotal genre paintings. Caravaggio may well have been familiar with earlier Netherlandish paintings of money lenders or of gamblers seated around a table like Saint Matthew and his associates.

Caravaggio represented the event as a nearly silent, dramatic narrative. The sequence of actions before and after this moment can be easily and convincingly re-created. The tax-gatherer Levi (Saint Matthew's name before he became the apostle) was seated at a table with his four assistants, counting the day's proceeds, the group lighted from a source at the upper right of the painting. Christ, His eyes veiled, with His halo the only hint of divinity, enters with Saint Peter. A gesture of His right hand, all the more powerful and compelling because of its languor, summons Levi. Surprised by the intrusion and perhaps dazzled by the sudden light from the just-opened door, Levi draws back and gestures toward himself with his left hand as if to say, "Who, me?", his right hand remaining on the coin he had been counting before Christ's entrance.

The two figures on the left, derived from a 1545 Hans Holbein print representing gamblers unaware of the appearance of Death, are so concerned with counting the money that they do not even notice Christ's arrival; symbolically their inattention to Christ deprives them of the opportunity He offers for eternal life, and condemns them to death. The two boys in the center do respond, the younger one drawing back against Levi as if seeking his protection, the swaggering older one, who is armed, leaning forward a little menacingly. Saint Peter gestures firmly with his hand to calm his potential resistance. The dramatic point of the picture is that for this moment, no one does anything. Christ's appearance is so unexpected and His gesture so commanding as to suspend action for a shocked instant, before reaction can take place. In another second, Levi will rise up and follow Christ_in fact, Christ's feet are already turned as if to leave the room. The particular power of the picture is in this cessation of action. It utilizes the fundamentally static medium of painting to convey characteristic human indecision after a challenge or command and before reaction.

The picture is divided into two parts. The standing figures on the right form a vertical rectangle; those gathered around the table on the left a horizontal block. The costumes reinforce the contrast. Levi and his subordinates, who are involved in affairs of this world, are dressed in a contemporary mode, while the barefoot Christ and Saint Peter, who summon Levi to another life and world, appear in timeless cloaks. The two groups are also separated by a void, bridged literally and symbolically by Christ's hand. This hand, like Adam's in Michelangelo's Creation, unifies the two parts formally and psychologically. Underlying the shallow stage-like space of the picture is a grid pattern of verticals and horizontals, which knit it together structurally.

The light has been no less carefully manipulated: the visible window covered with oilskin, very likely to provide diffused light in the painter's studio; the upper light, to illuminate Saint Matthew's face and the seated group; and the light behind Christ and Saint Peter, introduced only with them. It may be that this third source of light is intended as miraculous. Otherwise, why does Saint Peter cast no shadow on the defensive youth facing him?

The Conversion of St. Paul (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Conversion of St. Paul for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1600 Caravaggio received the commission for two paintings on cypress panel, one (Conversion of St. Paul) for the new chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. The extant painting with the subject is on canvas. The version in the Odeschalci Balbi Collection is on cypress wood as stipulated in the contract of 1600. It is probably a copy therefore it can be assumed that there was one time an original by Caravaggio.

a high-quality picture of

The Conversion of St. Paul for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1600 Caravaggio received the commission for two paintings on cypress panel, one (Conversion of St. Paul) for the new chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. The extant painting with the subject is on canvas. The version in the Odeschalci Balbi Collection is on cypress wood as stipulated in the contract of 1600. It is probably a copy therefore it can be assumed that there was one time an original by Caravaggio.

In the position of the St Paul and of the Christ, and in the movement of the horse into the depth of the picture, this work is still related to the tradition of Michelangelo's fresco in the Paolina Chapel. There are decidedly Caravaggesque elements in the work, such as the face of the angel supporting Christ, which greatly resembles that of the Amor Victorious (Berlin), or of the Isaac in the Sacrifice of Isaac (Uffizi).

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus (Detail) (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

As compared with the first version, the valid version, painted on canvas in contravention of the letter of the contract, reduces the incident to what is visible. Instead of looking like a figure modeled on a classical river-god, as he does in the first version, Saul now appears boldly foreshortened. The model Caravaggio has chosen is markedly younger, though is again wearing Roman leather-armor, which follows the contours of his body. That said, powerful red coloring and clearly defined borders, as well as the shadow areas on Saul's neck, now emphasize the difference between skin and armor.

a high-quality picture of

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

As compared with the first version, the valid version, painted on canvas in contravention of the letter of the contract, reduces the incident to what is visible. Instead of looking like a figure modeled on a classical river-god, as he does in the first version, Saul now appears boldly foreshortened. The model Caravaggio has chosen is markedly younger, though is again wearing Roman leather-armor, which follows the contours of his body. That said, powerful red coloring and clearly defined borders, as well as the shadow areas on Saul's neck, now emphasize the difference between skin and armor.

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1600, soon after he had completed the first two canvases for the Contarelli Chapel, Caravaggio signed a contract to paint two pictures for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. The church has a special interest because of the works it contains by four of the finest artists ever to work in Rome: Raphael, Carracci, Caravaggio and Bernini. It is probable that by the time Caravaggio began to paint for one of its chapels, The Assumption by Annibale Carracci was in place above the altar. Caravaggio's depictions of key events in the lives of the founders of the Roman See have little in common with the brilliant colours and stylized attitudes of Annibale, and Caravaggio seems by far the more modern artist.

a high-quality picture of

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus for your computer or notebook. ‣

In 1600, soon after he had completed the first two canvases for the Contarelli Chapel, Caravaggio signed a contract to paint two pictures for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. The church has a special interest because of the works it contains by four of the finest artists ever to work in Rome: Raphael, Carracci, Caravaggio and Bernini. It is probable that by the time Caravaggio began to paint for one of its chapels, The Assumption by Annibale Carracci was in place above the altar. Caravaggio's depictions of key events in the lives of the founders of the Roman See have little in common with the brilliant colours and stylized attitudes of Annibale, and Caravaggio seems by far the more modern artist.

Of the two pictures in the chapel the more remarkable is the representation of the moment of St Paul's conversion. According to the Acts of the Apostles, on the way to Damascus Saul the Pharisee (soon to be Paul the Apostle) fell to the ground when he heard the voice of Christ saying to him, 'Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?' and temporarily lost his sight. It was reasonable to assume that Saul had fallen from a horse.

Caravaggio is close to the Bible. The horse is there and, to hold him, a groom, but the drama is internalized within the mind of Saul. He lies on the ground stunned, his eyes closed as if dazzled by the brightness of God's light that streams down the white part of the skewbald horse, but that the light is heavenly is clear only to the believer, for Saul has no halo. In the spirit of Luke, who was at the time considered the author of Acts, Caravaggio makes religious experience look natural.

Technically the picture has defects. The horse, based on Durer, looks hemmed in, there is too much happening at the composition's base, too many feet cramped together, let alone Saul's splayed hands and discarded sword. Bellori's view that the scene is 'entirely without action' misses the point. Like a composer who values silence, Caravaggio respects stillness.

Both this and the following painting appear to be second versions, for Baglione states that Caravaggio first executed the two pictures 'in another manner, but as they did not please the patron, Cardinal Sannesio took them for himself'. Of these earlier versions, only The Conversion of St Paul survives.

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (Detail) (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Caravaggio has painted St Peter's body with his astonishing feeling for anatomy and the skin structure of an elderly male physique. At the same time, he has chosen the very instant when the Prince of the Apostles is raised into the undignified position in which he will be crucified - upside-down.

a high-quality picture of

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Caravaggio has painted St Peter's body with his astonishing feeling for anatomy and the skin structure of an elderly male physique. At the same time, he has chosen the very instant when the Prince of the Apostles is raised into the undignified position in which he will be crucified - upside-down.

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Crucifixion of St Peter in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo is one of two paintings in the Cerasi Chapel. Three shady characters, their faces hidden or turned away, are pulling, dragging and pushing the cross to which Peter has been nailed by the feet with his head down.

a high-quality picture of

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Crucifixion of St Peter in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo is one of two paintings in the Cerasi Chapel. Three shady characters, their faces hidden or turned away, are pulling, dragging and pushing the cross to which Peter has been nailed by the feet with his head down.

Caravaggio's St Peter is not a heroic martyr, nor a Herculean hero in the manner of Michelangelo, but an old man suffering pain and in fear of death. The scene, set on some stony field, is grim. The dark, impenetrable background draws the spectator's gaze back again to the sharply illuminated figures who remind us, through the banal ugliness of their actions and movements - note the yellow rear and filthy feet of the lower figure - that the death of the apostle was not a heroic drama, but a wretched and humiliating execution.

The Lute Player (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Lute Player for your computer or notebook. ‣

Two pictures (one in The Hermitage, St. Petersburg, and the other in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) of almost the same dimensions depict a boy with soft facial features and unusually thick brown hair, pouting lips, a half-open mouth and a pensive expression beneath sharply-drawn broad eyebrows. His white shirt is open at the front, revealing the artist's intention to paint a nude. This figure has the same dimensions in both pictures, which suggests that Caravaggio traced one on to oil-paper. In this case only one picture was completed from a fresh study of a model.

a high-quality picture of

The Lute Player for your computer or notebook. ‣

Two pictures (one in The Hermitage, St. Petersburg, and the other in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) of almost the same dimensions depict a boy with soft facial features and unusually thick brown hair, pouting lips, a half-open mouth and a pensive expression beneath sharply-drawn broad eyebrows. His white shirt is open at the front, revealing the artist's intention to paint a nude. This figure has the same dimensions in both pictures, which suggests that Caravaggio traced one on to oil-paper. In this case only one picture was completed from a fresh study of a model.

A sort of ribbon woven into the figure's hair emphasizes its almost androgynous features. The same applies - in the New York version - to a broad yoke which divides his shirt under his chest like a woman's dress. This is undoubtedly why Bellori saw this as a female lute-player, although recently it has been suggested that the model was a castrato. Light falls from a high window above left, creating a narrow triangle of brightness in the upper right-hand corner. That said, the brightly illuminated figure stands out boldly against the shadowy background.

The strongly foreshortened lute with its bent key-board demonstrates Caravaggio's virtuoso handling of perspective. Tactile elements project towards the viewer more successfully than in the New York Concert. As in the Uffizi Bacchus, the artist places a broad table-top in front of the figure - in the St. Petersburg version it is made of marble, and in the New York version covered with an oriental carpet.

The objects in the picture include an open book of music lying on another which bears the inscription "Bassus" in Gothic script, whilst the body of a violin serves to hold the book open at the right page. In both versions Caravaggio has painted the scores of older compositions clearly enough for us to read them. The music in question is the base voice-part of a popular collection, the "libro primo" of Jacques Arcadelt, which contains other compositions as well as works by this composer. Although the artist has cut off one row of notes, he has reproduced the initial notes so exactly that in the St. Petersburg example we can recognize the Roman printer, Valerio Dorica, whereas in the second version we can see that the book was published in Venice by Antonio Gardane.

In the St. Petersburg version, the violin bow lies across the strings and the open book of music - a prominent object for the observation of light and shade. In the New York version it is handled in a much less interesting way. Placed underneath the violin scroll, the bow can scarcely be distinguished from the brownish pattern of the carpet. In this version, a stout recorder and a triangular keyboard instrument are the other objects we see. The X-ray picture shows that they were painted over a still-life. The bird-cage motif in the left-hand corner (barely visible on the photo) shows what unusual motifs Caravaggio liked to select - motifs similar to those preferred by Caravaggesque painters in the Netherlands.

The St. Petersburg version, on the other hand, plays with the motifs of Caravaggio's other early arrangements of still-life and individual figures. Pieces of fruit lie on the marble slab, extremely brightly colored and brilliantly painted. A crystal vase contains a bunch of flowers, which would have made even Jan Bruegel the Elder jealous. The colors are applied uninhibitedly with a loaded brush - with a richness and precision we do not see elsewhere in Caravaggio's work.

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (Detail) (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

A boy who acts as altar-boy to the old man, whose service has been interrupted, flees screaming to the right. He is one of those expressive studies of emotion which, like the Medusa in Florence, have contributed greatly to Caravaggio's renown.

a high-quality picture of

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

A boy who acts as altar-boy to the old man, whose service has been interrupted, flees screaming to the right. He is one of those expressive studies of emotion which, like the Medusa in Florence, have contributed greatly to Caravaggio's renown.

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (1600)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew for your computer or notebook. ‣

Nothing that Caravaggio had done before was equal in scale, majesty or beauty to the first painting he produced for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, the French Church in Rome. The Martyrdom of St Matthew hangs on the right wall of the Contarelli Chapel and is lit from the left, as if from the window behind the altar.

a high-quality picture of

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew for your computer or notebook. ‣

Nothing that Caravaggio had done before was equal in scale, majesty or beauty to the first painting he produced for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, the French Church in Rome. The Martyrdom of St Matthew hangs on the right wall of the Contarelli Chapel and is lit from the left, as if from the window behind the altar.

The location is the steps up to a Christian altar, with a Greek cross marked on its frontage, and a candle burning. In the background on the left, we can just make out the shaft of a column in the almost impenetrable darkness. Steps ascend parallel to the picture towards the altar at the back. They also appear on the left, where churches do not normally have steps. For this reason some experts have claimed to detect a baptismal font in the foreground, especially as men are lying nearby, half-naked. On the left, a man is leaning against a step. He has no more concrete a role than two youths crouching in the foreground on the right, staring at the main action. They form the right-hand border of the composition, like river-gods on classical reliefs.

The picture's main figure is also half-naked. This is not the martyr, but his executioner. In terms of stroboscopic figures, his feet are level with the falling figure to his left. He has emerged from the depth of the picture to stand near the altar. This is hard to understand in a pictorial narrative which ought to be clarifying the passage of time in spatial terms. Insofar as the murderer has associated himself with the half-naked man in the foreground, left, the fall of the latter suggests that his power will also be shortlived.

Yet what Caravaggio is really depicting is the murderer's moment. He has thrown St Matthew, a bearded old man, to the ground. As a priest, he is wearing alb and chasuble. Whilst his victim helplessly props himself up on the ground, the Herculean youth seizes his wrist in his right hand, to hold the victim still for the death-blow. Yet the apostle's attempt to ward off his murderer, with his furious face, turns into a different gesture as an angel extends a martyr's palm-leaf to his open hand.

Caravaggio Art

|

|

More

Articles

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Art Encyclopedia A world history of art in articles.

Baroque

Caravaggio

Art and life. Biography.

Early paintings by Caravaggio.

Late paintings by Caravaggio.

Art

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Art Wallpapers Art image collections for your desktop.

Caravaggio Art, $25

(100 pictures)

Rubens Art, $29

(200 pictures)

Rembrandt Art, $25

(160 pictures)